Business owners and nonprofit leaders who spoke at a roundtable discussion last week about potentially raising the minimum wage in Long Beach said they are divided on the issue, stating that they support higher pay for workers but that increasing wages too rapidly would create a financial burden they are unprepared for, and in some cases unable to bear.

During the gathering at Admiral Kidd Park in West Long Beach on November 17, nearly a dozen people, including workers, nonprofit representatives, business owners and restaurateurs, participated in the roundtable discussion led by Mayor Robert Garcia, followed by public comment. Some speakers attended a similar roundtable held in Bixby Knolls two weeks prior.

The roundtable last week took place just days after a study on the feasibility and potential implications of a citywide minimum wage policy conducted by the Los Angeles County Economic Development Commission (LAEDC) was released to the public.

The gathering was part of a series of community outreach meetings organized by the city in the last two months to collect input on how, or if, Long Beach should move forward with a minimum wage policy after the City of Los Angeles and several other major cities across the country have raised wages in their respective jurisdictions.

Following a nationwide union-led movement, the City of Los Angeles passed an ordinance earlier this year that raises its minimum wage to $15 an hour incrementally by 2020, with the first increase going into effect next year, while giving small businesses with 25 or fewer employees more time to comply. The County of Los Angeles passed a similar law for unincorporated areas.

For Long Beach, the LAEDC study commissioned by the city council considered two possible scenarios– increasing the minimum wage to $12 an hour incrementally by 2017 and raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour incrementally by 2020.

The study indicates that, while some employees would benefit from higher wages, others may suffer, since employers might be forced to cut jobs or reduce employee hours.

Garcia reiterated during the roundtable that no official proposal for Long Beach would be brought forward until the issue has been fully vetted. He said the city’s economic development commission (EDC), which meets today at 6 p.m. at City Hall to discuss the issue, is expected to make a recommendation to the city council sometime early next year.

Steering clear from taking an official stance on the issue, Garcia said the ultimate goal of imposing a citywide minimum wage law is to “lift up the city” to a better standard of living by doing what’s in the “best interest” of the city long term.

Over the course of the past several weeks, however, a number of issues have been brought up, including those related to how a citywide minimum wage law would impact: businesses with tipped workers, such as restaurants, and commissioned employees; staffing agencies that fill temporary positions inside and outside of the city; and organizations that derive most income from state resources, including senior home care providers and nonprofits.

At the same time, fast food, warehouse and hotel workers have called for a $15-an-hour wage in addition to accompanying enforcement from the city. Many workers have brought forward claims of wage theft and being overworked. One mother stated she has worked for Taco Bell for nine years and still is paid minimum wage, which some questioned why she would continue working there.

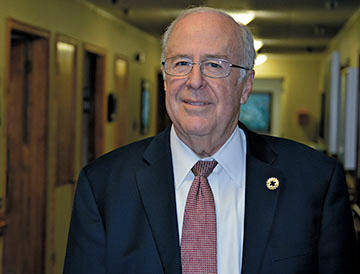

Alan Anderson, owner of Bel Vista Healthcare Center, a 41-bed skilled nursing facility for seniors, said he agrees with workers that the minimum wage should be increased but opposes raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2020, a 60 percent increase in wages over a four-year period.

Alan Anderson, is owner of Bel Vista Healthcare Center, a 41-bed skilled nursing facility for seniors in Long Beach. (Photograph by the Business Journal’s Larry Duncan)

“I agree the minimum wage is too low and I think it should be higher, but, as it’s been proposed, it’s too much, too fast,” he said, adding that such a wage increase would create unintended negative consequences, particularly for senior care providers.

Anderson explained that, if privately run care providers, including skilled nursing facilities, assisted living facilities and in-home supportive services, are required to increase workers’ wages above state levels, there would be no way to pass on increased labor costs to consumers since most seniors are covered through Medi-Cal or Medicare and income for these facilities is mostly governed by the state and federal government.

Anderson said raising the minimum wage in Long Beach would ultimately make home and health care services for seniors more expensive and would potentially cause seniors to be “priced out of their own homes” because they would no longer be able to afford it and would be forced to live in less expensive institutions.

Additionally, many facilities are aggressively competing to fill beds since Long Beach is currently “over-bedded” with more senior care skilled nursing facilities than are needed, he said. Many facilities were built in the 1960s when seniors moved to the city from the Midwest. Anderson added that that there are 27 nursing homes in the city, with more than 3,100 beds and approximately 4,982 employees.

Also, Anderson, who once served as president of a local chapter of the California Association of Health Facilities (CAHF), told the Business Journal that such facilities aren’t able to cut employees like other businesses because nursing facilities have a moral obligation to make sure patients are taken care of and staffing patterns are regulated by the state.

Bel Vista Healthcare Center located at 5001 E. Anaheim St. in Long Beach is one of 27 nursing homes in the city that may be impacted negatively if Long Beach passes a law that would increase the minimum wage, according to the facility’s owner Alan Anderson. (Photograph by the Business Journal’s Larry Duncan)

On top of the state’s minimum wage increase, other labor costs have increased as well, he said, adding that he now pays $138,000 more a year for workers’ compensation insurance for 63 employees. Anderson said the state’s new paid sick leave law has also added costs since he has to pay employees overtime for shifts since part-time workers are now taking sick days.

Restaurant owners expressed their own concerns with raising the minimum wage, including that it would force them to raise prices, putting them at a competitive disadvantage with restaurants in other cities.

Mike Rhodes, owner of Domenico’s, an Italian restaurant on 2nd Street in Belmont Shore and considered the oldest restaurant in Long Beach, suggested that, if the city moves forward with a minimum wage policy, tipped employees, who make significantly more than minimum wage after taking home tips, should be carved out and be allowed to follow the state’s wage rate.

He added that raising the minimum wage in a citywide law might only encourage a recent movement by some restaurateurs to eliminate tips all together.

Garcia said the city attorney’s office is currently investigating whether there would be any legal challenges in exempting tipped employees in a proposed minimum wage policy.

Rhodes and other restaurant owners said their biggest concern is that passing minimum wage legislation at the city level would create a competitive disadvantage. He added that union-sponsored organizations that have pushed the “Fight for $15” campaign should be lobbying for legislative changes in Sacramento instead of at city hall to maintain a level playing field.

In response, Garcia noted that proposals are currently being deliberated to increase California’s minimum wage. A statewide proposal may be voted on in a ballot measure for the November 2016 election, an issue that will ultimately be part of the discussion of whether Long Beach should pass its own minimum wage law, he said.

Wayne Slavitt, owner of Mobül: the home mobility store, which provides medical and mobility equipment in Long Beach, said employees who receive commissions should also be taken into account when considering exemptions from any citywide minimum wage increase.

He added that profits are important for businesses to grow and businesses often have to cut jobs if labor costs are too high. Slavitt added that minimum wage positions were meant to be entry level jobs and not meant for people in their 30s, 40s and 50s who are supporting a family.

Slavitt said the city should be devoting more resources to job training opportunities for people to seek higher-paying jobs rather than simply mandating higher wages.

During public comment, Christine Petit, hub manager for the nonprofit Building Healthy Communities in Long Beach, said a recent survey of 80 nonprofit organizations in the city found that 75 percent of the respondents indicated that they would support a minimum wage increase without exceptions.

As part of the roundtable discussion, however, nonprofit leaders expressed concerns with covering higher labor costs, noting that many nonprofit organizations receive a majority of income from state reimbursements, which are limited. Still, nonprofit leaders also expressed a need to pay their employees more, noting that some nonprofit workers are able to qualify for the same low-income assistance programs for which they work.

“We have a very limited reimbursement from the state,” said Sarah Soriano, executive director of Young Horizons Child Development Center, which provides child development services to hundreds of low-income families in Long Beach. “How are we going to make ends meet? At the same time, how does my staff qualify for my own low income program?”