In November 2018, the Long Beach Public Works Department received the results of a study conducted by the firm HF&H Consultants, which concluded that the city’s current residential waste disposal rates were insufficient to cover the cost of service for the department’s approximately 142,000 households. Now, the city is planning to raise refuse rates for residential clients in two phases, starting in March.

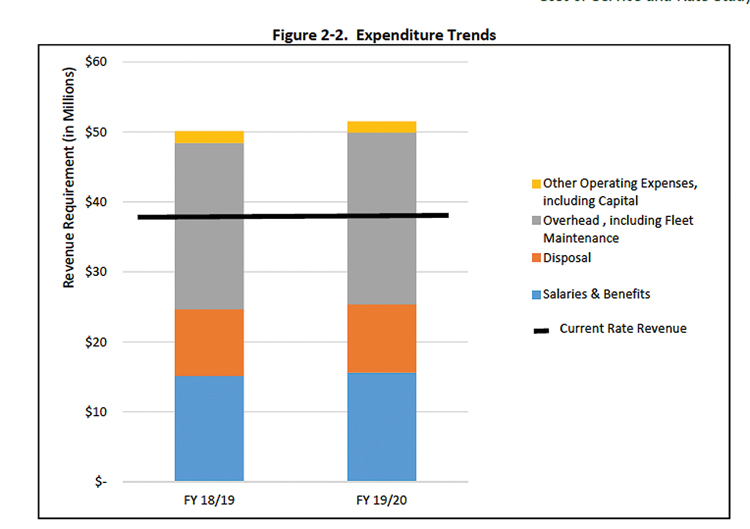

In its study, the consulting firm found a deficit of $7.8 million dollars between the expected cost of the waste disposal services offered by the city and the revenue collected from customers in the fiscal years of 2018 and 2019.

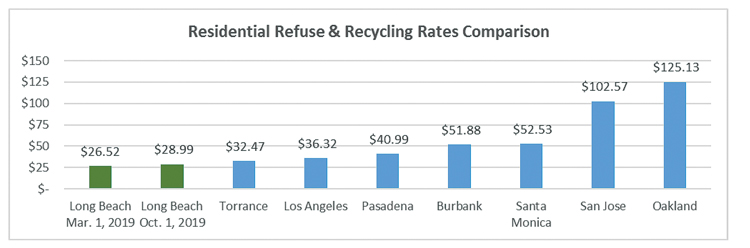

Residential clients who live in single-family homes or apartment buildings that produce less than 1,000 gallons of waste per week – which is roughly equivalent to the waste production of a 10-unit complex – and small businesses are serviced by the city’s public works department and would be affected by the proposed rate hike. The first phase would increase rates for the weekly collection of 100-gallon carts from $24.11 to $26.52, and the second would increase the monthly rate to $28.99.

Public works hasn’t increased residential rates since 2002, according to the department’s deputy director, Diko Melkonian. Since then, rising costs for fuel, vehicles, disposal fees and labor have made it costlier for the department to provide services. Reduced revenues from waste products and increased requirements implemented by the state have added to the financial burden. “The recycling markets have taken quite a dive in the value of most commodities; you don’t get nearly as much back,” Melkonian said. “Costs increase, mandates increase, and you have to fund them somehow.”

Additionally, the city is planning another study to prepare for new state requirements on organics disposal to be rolled out in 2022. “Some of this money is going to be used to prepare us for that,” Melkonian said. The study is expected to publish in late 2020, and might call for another increase leading up to the new requirements put forward by Senate Bill 1383, which is related to organic waste recyclcing.

“We’ll be looking at the greater impacts of these new rules from the state. Right now, we’ve essentially built in the cost of developing the plan,” Melkonian said. A further rate increase is likely, however. “The infrastructure isn’t there to support [organics collection]. If all the cities in Southern California would all of a sudden collect organics, there wouldn’t be anywhere to take all of it,” Melkonian said. “The only way you can fund that infrastructure is by raising the rates on the service you provide.”

The increase in rates will also help fund some of the expansions in service the city is already offering, for example in the form of four free bulky item pick-ups per year and expanded hours at the city’s hazardous household waste disposal center in Signal Hill.