For years, it was sunny skies for the cruise industry. Not even the Great Recession could slow its momentum. Carnival Corporation, the world’s dominant cruise line, was so confident of the future that it launched plans in 2015 to build one of its biggest ships, the Panorama, which would be based in Long Beach.

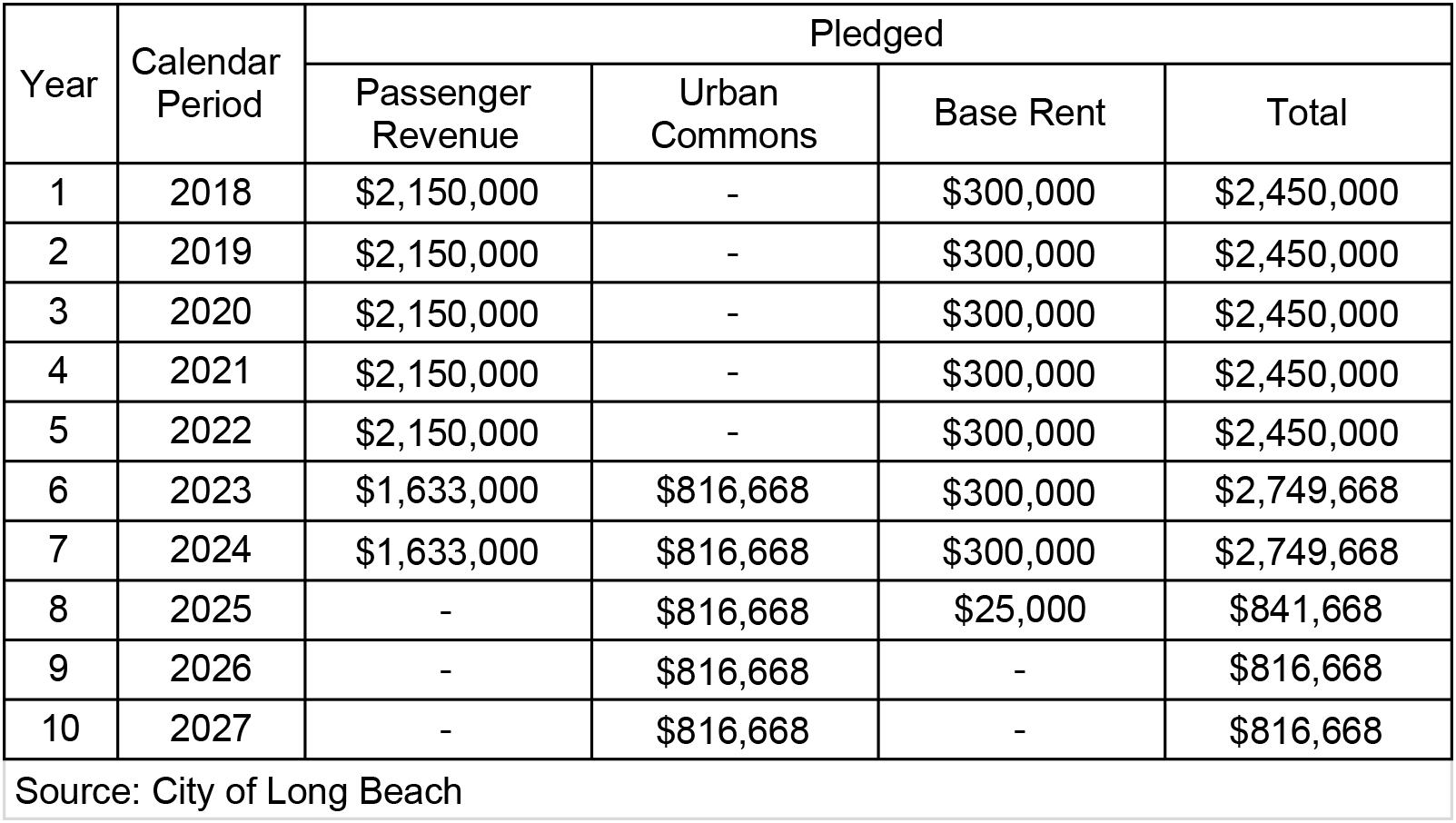

The Long Beach City Council was confident too, so much so that it voted in 2016 to use fees collected from the growing numbers of passengers to underwrite a $23 million bond measure for critical repairs to the ailing Queen Mary. As collateral for the bonds, which would be repaid over 10 years, the city pledged money from its Tidelands Fund.

Then came the storm–the coronavirus pandemic. It has not only battered the cruise industry but also has undermined the financial strategy created by the city during those brighter days. With the bond money already spent and passenger fees gone for now, the city is being forced to pull money out of the Tidelands Fund, potentially affecting other coastal projects.

Last month, Carnival Corporation reported a record $4.4 billion in quarterly losses and extended its cruise cancellations through Sept. 30, meaning a substantial loss of money to the City of Long Beach. The company has three ships based near the port, and the city collects $3 for each passenger.

Just months ago, city leaders had been anticipating a significant increase in passenger traffic and dollars with the arrival late last year of the Panorama, which can accommodate more than 4,000 passengers—nearly double that of its other vessels. They predicted that the city would net around $3 million annually in passenger fees from the new ship alone.

Long Beach Financial Management Director John Gross said in an interview that Tidelands monies will now be used to pay the still-unknown shortfall in passenger fees for fiscal year 2021, which begins Oct. 1. No additional shortfalls are anticipated in subsequent years, he said, “assuming carnival cruise gets back to normal operations.”

The Tidelands Fund provides critical money for operations and development of beaches and waterways in the city. The fund is fed through a variety of sources that include oil revenues, recreational boat slip fees, ground leases for marina-adjacent properties and annual transfers from the harbor department, which oversees the Port of Long Beach.

Development projects currently underway or slated to be financed by Tidelands monies include beach concession stands, the proposed Belmont aquatics facility and upgrades to the Belmont Pier. The fund also pays for operations at the Long Beach Convention & Entertainment Center, lifeguards, maintenance of sea walls and upkeep of beach restrooms.

At this point, the full impacts of COVID-19 on the Tidelands budget and future projects remains uncertain, depending on the duration of the crisis and its lingering impact on the cruise economy.

Fifth District Councilwoman Stacy Mungo, outgoing chair of the city’s Budget Oversight Committee, explained that Tidelands capital improvement projects are funded gradually, with no firm start date until the money is available.

“While there are many projects that are on our wish list, those projects are only pulled off the list as we can afford them,” Mungo said in an interview. In other words, some projects may now stay on the wish list longer than envisioned.

When the bond financing plan was passed by the City Council four years ago, not everyone was on board.

The bonds were a key element of a master lease agreement that Long Beach struck with the real estate investment development firm Urban Commons to become the operator of the city-owned Queen Mary and adjacent land.

The city agreed to offer the $23 million in bonds as an upfront payment for emergency repairs on the ship, which Urban Commons would be responsible for ensuring were completed. The city would then be reimbursed through the ongoing passengers fees.

Third District City Councilwoman Suzie Price was the only dissenting vote. She said she had concerns about using the Tidelands Fund as collateral. Price had a particular stake in the deal because money from those funds can only be used for projects in the two districts that front the coastline, which includes hers.

Financial management director Gross tried to assure Price that passenger fees from Carnival operations were stable and that using the Tidelands Fund as collateral was low risk and should not be a “significant consideration.”

Although no one could have anticipated the coronavirus collapse of the cruise industry, Price turned out to be ahead of her time.

“I had serious hesitation about leveraging Tidelands Funds at the time we entered into the agreement with Urban Commons,” Price said. The unprecedented pandemic, she said, now “has put us in a very vulnerable position.”

Reservations were also expressed during the council meeting by City Auditor Laura Doud, who requested additional time to review the agreement. She was mostly concerned about the financial viability of Urban Commons, not the Tidelands Fund, knowing that the Queen Mary repairs would far exceed the amount of the bond measure.

“The Queen Mary is one of the largest city-owned financial assets—it has such a historical significance in our city that I feel like this discussion was worthy of more than a quick $23 million fix,” Doud said in a recent interview. “I felt that it was really a ‘Band-Aid’ approach.”

Nonetheless, the council decided to press ahead.

Councilwoman Mungo said that, although the pandemic’s devastating punch was unforeseeable, she believes the city is in a position to weather the financial impact, including on funds earmarked for specific purposes, such as the Tidelands Fund.

“Long Beach works hard to ensure that those restricted funds have a multitude of sources so that hopefully all those sources are not impacted at once,” Mungo said. “This global pandemic has been a strain on so many different facets and factors. We are doing better than some cities that don’t have that kind of diversity in their revenue. But we need to do even better.”

The loss of passenger fees is not the first blow to the Tidelands Fund since the COVID-19 outbreak. In April, the pandemic took a toll on the oil industry when futures prices fell below $0 per barrel for the first time in history. The Tidelands Fund receives a large chunk of its monies through oil and, for fiscal year 2020, the city is anticipating a $6 million shortfall in that revenue.

The Tidelands’ 2020 budgeted revenue was $78.4 million based, on an estimated $12.6 million from oil revenue, according to Gross. The city’s fiscal 2021 budget must be approved before October 1.

With several states, including California, re-closing some businesses such as bars in the wake of a surge of COVID-19 cases, there is a chance that renewed cruise operations will be delayed even longer than what has already been announced.

To make up for losses, Carnival announced it will sell six of its ships but has yet to identify which brands and vessels will be affected. The Florida-based company operates 106 ships across eight brands, including Carnival Cruise Lines, AIDA Cruises, Costa Cruises, Cunard, Holland America, P&O Cruises, Princes Cruises and Seabourn.

The two smaller ocean liners the company owns in Long Beach are among the oldest in the Carnival fleet. The Inspiration recently appeared on the website Global Ferry & Cruise Shipbrokers, listed for sale for $200 million.

“We have asked the company in question to remove our ship from the site as it is not correct and we have not announced which ships will be affected,” a Carnival spokesperson said in an email.

A carnival spokesperson said an announcement will be made within 90 days.