39 City Employees Part Of New $200,000 Club;

Union ‘Skill Pay’ To Cost Taxpayers $25.6 Million

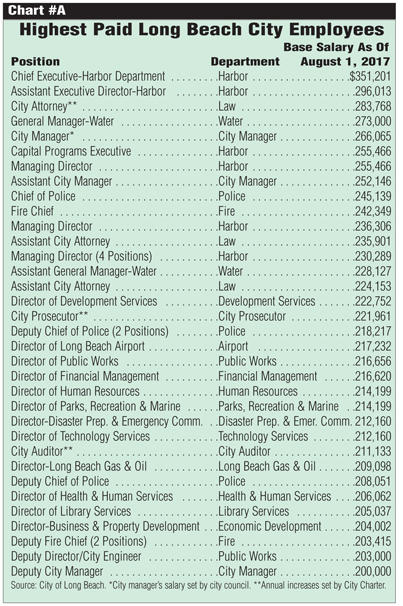

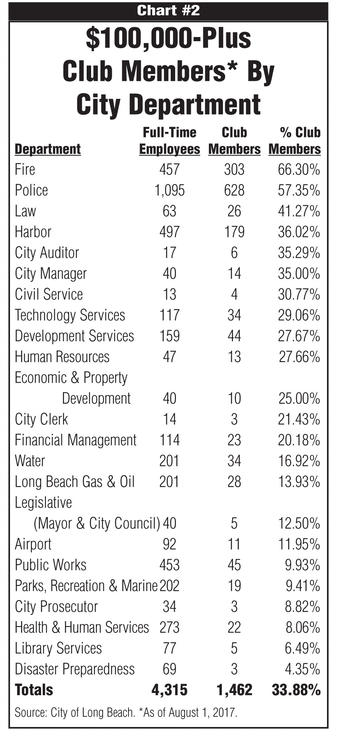

Memorandums of understanding with several of the city’s unions have resulted in a spike in the number of employees earning a base salary of $100,000 or more, while 39 city workers have eclipsed the $200,000 mark (See Chart A). Those numbers will increase October 1 with the new budget, as pay raises kick in for a majority of city employees.

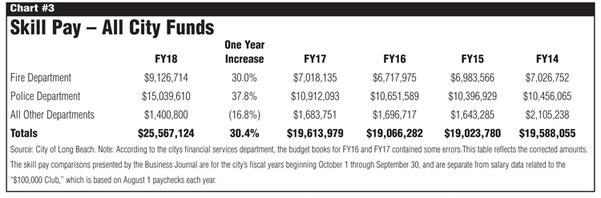

An issue that should elicit questions from residents and business owners who are now paying more in taxes to “assist” the city with infrastructure and public safety needs, is the $25.6 million budgeted for what is known as “skill pay” – nearly all of it going to public safety personnel. Evidently, city councilmembers approved enhanced “skill pay” dollars as part of the recent negotiations with police and fire unions. In addition to skill pay, the police and fire departments have a combined $27.1 million budgeted for overtime. Skill pay and overtime account for approximately 11% of the city’s General Fund budget. More about these items later in this article.

About The

$100,000 Club

The Business Journal’s “$100,000 Club” (click here to view PDF of full breakdown of salaries by position) was launched in the late 1990s; long before public sector salaries were available on the Internet for all to see. In 2009, the city manager’s office offered to work directly with LBBJ staff to ensure accurate information was being presented. During the past nine years, the Business Journal has listed city salaries based on August 1 paychecks. This has allowed for an annual apples-to-apples comparison of salaries, benefits, pay increases, employee counts and other information – much of which is presented in charts and lists in this edition.

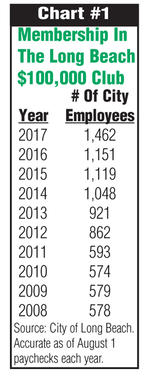

As Chart #1 indicates, membership in the “$100,000 Club” jumped by 45% in 2012, and this year increased by 27% – both jumps are tied to new memorandums of understanding with unions.

In fairness to city employees, they helped the city when the recession cut deeply into city revenues from 2009 to 2012. Police, fire and other unions agreed that their employees would pay the entire “employee fee” for pensions (they had been contributing a small percentage). Many members of the community argued for years, however, that employees should have been paying the full fee all along – which amounted to 9% of base salary for sworn personnel and 8% for nearly all other employees. Nevertheless, the city had been covering the employee fee for decades, so it was considered a give back by employees.

As Chart #2 shows, 33.88% of the city’s 4,315 full-time employees (as of August 1, 2017) receive a six-figure-plus base salary. While many people in the public sector argue that a $100,000 salary “isn’t what it used to be,” it remains about double the household income in Long Beach. Roughly 20% of the city’s nearly 475,000 residents are considered low-income, and another large percentage of residents are living paycheck to paycheck, challenged by escalating rent costs that are sapping half of their salary.

The fire department has the highest percentage of “club” members – 66.3% – of full-time employees making $100,000 or more, followed by the police department at 57.4%. Combined, their employees represent about 64% of the “$100,000 Club” members. These percentages will increase slightly on October 1 when the second of three, 3% pay raises goes into effect (most non-public safety employees will receive a 2% increase).

Wages

While there are some city departments – and some specific positions – with eye-popping salaries, it may surprise readers that the overall city payroll is in line with increases to the region’s consumer price index (CPI).

In June 2009, the U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, indicated that the CPI for the Los Angeles-Riverside-Orange County area was 223.906 (the base year of 100.0 was in 1982-84 – meaning, what cost consumers $100 in 1982-84, cost $224 in 2009). In June 2017, the CPI was 255.275. That’s a 14% increase over the past 9 years.

By comparison, the annual city payroll based on August 1, 2009, paychecks, was $383,570,104 for 5,822 full and part time people. This year, August 1, 2017, the payroll totaled $434,645,158 for 5,656 employees. That’s a 13.3% increase in total payroll and a 16.6% increase in average annual wages (payroll divided by the number of employees receiving checks).

Union negotiations – especially for sworn personnel – are usually based on what “comparable cities” or agencies in the region are paying for similar positions, such as a firefighter or police officer. The comparison list for police are the cities of Anaheim, Glendale, Huntington Beach, Los Angeles, Pasadena, Torrance, Santa Ana and Santa Monica, as well as L.A. and Orange County sheriffs departments. The most recent MOU brings base pay for Long Beach public safety personnel to the mid-point of those agencies, according to city staff.

Curiously, one Long Beach position that continues to be considerably below average is that of city manager, whose salary is set by the city council. While Pat West’s salary is currently a healthy $266,000, it pales in comparison to city managers in cities such as Santa Ana, Santa Monica, Torrance, Burbank, Irvine, Anaheim, Gardena, Culver City, Chino, Lakewood, Compton and 50 others in the state that are at $300,000-plus, according to the California State Controller’s website. Additionally, few city managers have the responsibilities that come with the Long Beach job: a port and airport as well as water, health and gas-oil departments, plus more than 5,000 employees to oversee. West, who was named city manager in September of 2007, however, is not complaining. “I’m happy,” he said.

Skill Pay And Overtime

As defined in the budget document, skill pay is “additional compensation specific for specialized skills that enhanced an employee’s job performance.” It sounds reasonable, but taxpayers are on the hook for $25.6 million in the coming fiscal year, nearly all of it going to public safety personnel. This represents a 30% increase in skill pay costs from the current 2017 fiscal year, even though relatively few employees have been added to the fire or police departments. This is significant considering the fiscal challenges facing the city and public demands for more police officers on the street.

The skill pay arrangements are outlined in the MOUs, which means city councilmembers were aware of the costs – or should have been – when they approved the new contracts. As Chart #3 shows, the total cost of skill pay was nearly identical for the four previous years. Thus, it’s likely that skill pay is being used to boost public safety salaries.

Focusing on the police department, skill pay is provided for a number of “skills,” including being a motor officer, working in port security, serving as a helicopter pilot or observer, being bilingual, being assigned to a detective bureau or accident investigation detail. There is extra money for “marksmanship pay,” ranging from $4 a month for marksman to $32 a month for master. There is extra money for educational attainment: 2.75% for an associates degree; 5% for a bachelors and 6.5% for a masters, all based on a “Step 5 Police Officer” rate, which is just over $43 an hour. According to the city’s human resources department, 116 officers are receiving an extra $1.190 per hour for their AA; 282 officers are getting $2.164 per hour for having a bachelors degree; 60 officers are receiving $2.814 per hour for a masters degree; and 178 who are “working” toward getting a bachelors or masters degree are receiving $1.190 per hour. These payments continue until the officer leaves the city.

The above are a sampling. The fire department has its own set of skill pay categories.

To put the $25.6 million in perspective, more than 100 new police officers could be hired with that money, with sufficient funds left over to equip the force with body worn cameras – something that several councilmembers indicated publicly that they would like to see as soon as possible. (At the August 8 budget meeting, Police Chief Robert Luna explained to the city council that a study about the use of cameras should be completed in November. Funding for cameras has not been identified.) Another perspective: If the skill pay were cut in half, it would eliminate the $10.4 million budget shortfall estimated for Fiscal Year 2019.

In addition to the base pay and skill pay for public safety employees, more than $27 million is budgeted next year for their overtime. The fire department’s share is $15,502,183, which represents a 48% increase from the 2015 fiscal year budget. In 2015, the department had 459 full-time employees; next year it’s budgeted for 457. That’s only a 6% increase in the number of employees. The fire department has long claimed, and backed up by city officials, that it is less expensive to use overtime than to hire more firefighters.

Risk Pay Instead Of Skill Pay

The Business Journal has long supported that public safety personnel – especially police officers on the street – should be paid as much as the city can afford to pay. We would support, with a few exceptions, eliminating all skill pay and replacing it with “risk pay.” The men and women who are doing the tough work and who are putting their lives on the line on a daily basis – patrol, motors, detectives, gang detail, undercover, etc. – should be the highest paid members of the department. The current skill pay system rewards everyone irrespective of risk.

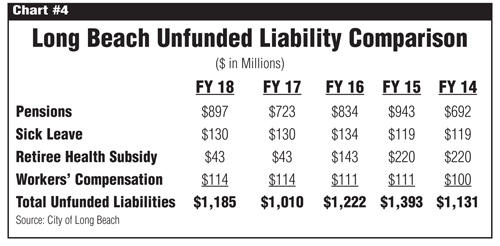

Pensions And Unfunded Liabilities

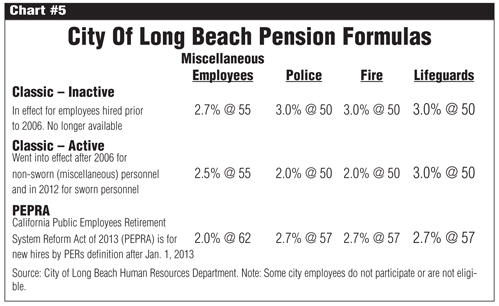

Unfunded liabilities – driven by pension costs – are an ongoing concern for Long Beach and most other cities in the state and country. The city is facing $1.185 billion in unfunded liabilities, with $897 million of that for pensions (See Chart #4). But a decade ago, while Bob Foster was mayor, the city attacked the pension issue on several fronts, including establishing new “pension formulas” (refer to Chart #5) and developing a 30-year plan (Assistant City Manager Tom Modica: “It’ll be fully funded. You’ll have zero for liability.”).