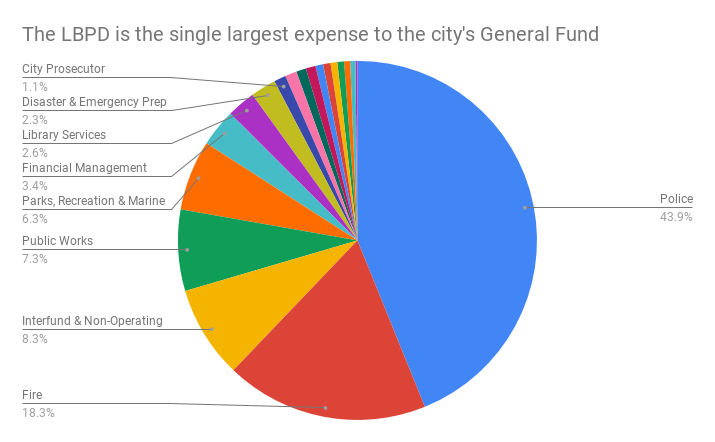

As waves of protests sweep across the county, there’s been new scrutiny on police departments’ budgets, which often eat up a large portion of cities’ discretionary spending.

In Long Beach, that’s no different. Last year, the city allocated 44% of its General Fund to the Long Beach Police Department, making it by far the most expensive department for local taxpayers. The budget office said the true percentage is closer to 48%.

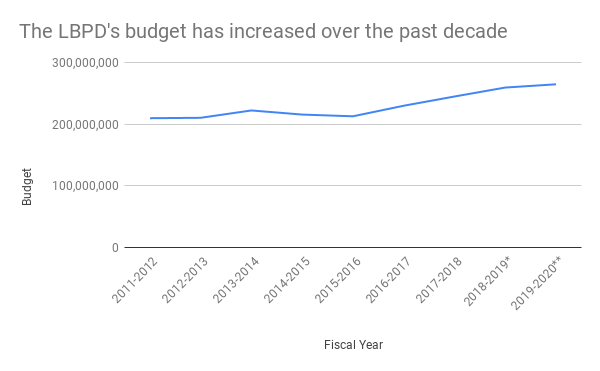

The department costs the city close to a quarter of a billion dollars per year, and its budget has increased over the past decade. Now, that funding is the target of activists who are outraged about the deaths of Black men and women at the hands of police.

Instead of paying for law enforcement, they argue, the money would be better spent on social services and community development. But what exactly does the LBPD spend its money on now?

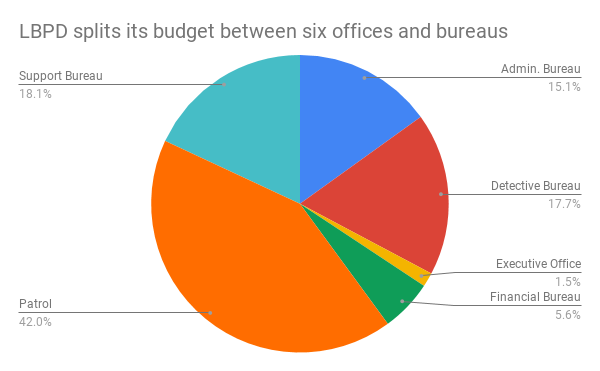

The LBPD’s budget for the current fiscal year is $265 million. The overwhelming majority of that money, $224 million, pays for salaries, benefits and overtime for employees, which includes about 800 sworn officers and 400 civilians.

A massive chunk of the overall budget is allocated to the Patrol Bureau, home to a majority of the LBPD’s sworn police officers. Out of a total of 792 officers, at least 600 are assigned patrol duty or to supporting the patrol officers who are doing day-to-day police work, including responding to 911 calls, taking reports and writing traffic tickets.

The Support Bureau, which covers jails, training and the port police—among other things—and the Detective Bureau, which houses the department’s investigative units, account for the largest expenditures outside of patrol. LBPD spends $47.7 million and $46.8 million on each bureau, respectively.

This leaves $59 million for the remaining three subdivisions, the Administration Bureau, the Financial Bureau and the Executive Office. There, big ticket items include information management, internal affairs and budget management.

From the budget, it can be difficult to suss out details in some areas, for instance, how much the department spends on training new and current police officers. The budget for training and communications expenses are lumped into one category that amounted to $6 million, or just over 2% of the department’s overall budget, in fiscal year 2020. The police academy cost another $1.4 million.

Instead of focusing on police reforms and putting more money into training, many activists across the country are now calling for defunding, which is the diversion of at least some funds away from police departments and toward social services and community development initiatives.

Long Beach is no exception. Several community organizations have banded together to call for similar shifts in funding in this year’s annual People’s Budget, though no specific cuts or shifts in funding were offered. The People’s Budget is an outline of priorities, not a list of specific line items.

That budget proposal, which is put together under the leadership of Long Beach Forward and supported by Black Lives Matter LBC, Sanctuary Long Beach Coalition, and Long Beach Gray Panthers, among others, calls on city leadership to “divest from the police and reinvest in communities of color.”

These demands are not new, said James Suazo, associate director of Long Beach Forward. But, he noted, “right now is an opportune time because we’re in a moment and part of this larger movement.” More people are realizing that the way policing has been done so far is not working, Suazo argued. “And it’s coming at the cost of human lives, and in particular, Black lives.”

Reinvestments could take the form of reimagined community safety, renter protections and affordable housing, language access, job training, senior and youth programming, and universal legal representation for immigrants, a joint press release said.

When it comes to calls for cuts to the department’s overall budget, LBPD’s Chief Financial Officer Velasco-Ventura said the city manager has asked all departments to provide proposals for a reduced budget to compensate for the loss in tax revenue caused by the coronavirus pandemic. However, City Manager Tom Modica has asked for far more stringent cuts of up to 12% by other departments, giving any public safety departments a target between 0% and 3.5%.

The police department’s proposal is due to be released in August, the CFO said.

One way advocates suggest moving funding away from the police department is by taking away the responsibility of responding to calls involving homeless residents and instead placing it in the hands of social services providers and mental health professionals.

There’s no data to show how much money the LBPD spends responding to calls related to homelesseness in particular, but police officers commonly respond to such calls with help from firefighter-paramedics, who can provide transportation to homeless services or the emergency room, if necessary.

Taking cops out of the equation is not a favorable option, Velasco-Ventura argued.

“In certain cases, there might be an enforcement issue related to trespassing or some other issue in which it is under the police department’s purview to utilize enforcement abilities to address that particular problem,” she said.

Velasco-Ventura said the LBPD has already been adapting its spending according to public input.

For example, when truancy enforcement fell out of public favor, LBPD cut its Youth Services Division, which had been mainly tasked with enforcement involving juvenile offenders—including truant teens.

Today, a community engagement officer and a cadet coordinator handle youth-focused programs, while juvenile crimes are handled by the investigations unit.

“There’s much more emphasis on juvenile diversion and leveraging community based organizations and programs,” Velasco-Ventura said. “Instead of focusing just on enforcement, it’s looking at their home, the family, mental health concerns, looking at education.”

In its jail, the department cut two jailer positions last year and eliminated a service that transported inmates to court. There weren’t enough inmates to justify the positions, the CFO explained. Instead, the department decided to fund an in-house mental health clinician.

“We try to convert that funding into something that either data or research or examples in other cities show produces a better outcome,” Velasco-Ventura said.