At the annual California State University, Long Beach (CSULB) Regional Economic Forum, economist Robert Kleinhenz told attendees that, come June, the United States will have achieved its second-longest period of economic expansion. Kleinhenz, who is the executive director of research for Los Angeles-based Beacon Economics, said that the expansion could ultimately break the country’s all-time record.

The sold-out event – presented by the CSULB Department of Economics, Office of Economic Research – took place on April 25 at the Long Beach Convention & Entertainment Center. Attendees ranged from academics to real estate professionals, financial services executives, city staff and elected officials, university students, and many other local professionals.

“We are closing in on the second longest economic expansion on record in the U.S. economy since World War II. Come June, it will become the second longest expansion on record,” Kleinhenz said. “I predict that we will continue to expand past that. And I would say that the longest expansion on record is probably within our sight.”

While Kleinhenz said he was growing tired of talking about the Great Recession, he explained that it remains an important factor in the economic stability the country is experiencing today. The recession is an influential factor in financial decision making, both for businesses and individuals, resulting in more cautious behavior, he said.

Kleinhenz noted that most economic indicators remain positive, including the nation’s full employment rate, wage growth and strong consumer spending. Gross domestic product (GDP) increased by 2.3% in 2017, and Kleinhenz said he expects 2018 to close out with 2.5% to 2.8% GDP growth.

GDP growth is being constrained by slowing growth in the labor force, Kleinhenz noted. Because the nation’s unemployment rate of 4.1% is essentially full employment, companies are having more difficulty filling positions, he explained. One way to resolve this, he argued, would be through immigration policy reform.

“We have in the past and we can now come up with a sound immigration policy that will allow us to expand our labor force to enable the economy to grow at its potential,” Kleinhenz said. “If you want to increase the potential for the economy to grow by more than 2%, you need to increase the labor force or make it more productive. And increasing the labor force at this time would most likely come if we can fashion an immigration policy that’s going to work for the employers as well as for the workers themselves.”

While the United States is currently operating a trade deficit of $619 billion due to an imbalance of imports coming into the country with far fewer exports leaving it, the reason behind this gap isn’t necessarily negative. “When the U.S. economy is doing well, as it has been for the last several years, we’re importing more stuff,” Kleinhenz said. “The trade deficit is really increasing because the economy is doing better and doing relatively better than our trade partners.”

Points of concern at the national level include a decreasing rate of savings among Americans and the high per capita cost of health care, which Kleinhenz pointed out is well above that of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Norway and other developed nations.

Overall, though, Kleinhenz had an optimistic outlook. “The vital signs of the U.S. economy right now are quite good. We expect this year to be a year of growth,” he said. “The tax cuts and the budget that was just passed will juice the economy for the next couple of years.”

At the state level, economic indicators are also strong. For example, taxable sales in the state increased by nearly 5% in 2017, and remain on “a nice, steady trajectory,” Kleinhenz noted California has just achieved its lowest unemployment rate on record at 4.3%. Its growth in state GDP and year-to-year job gains are among the highest in the nation, he added. Of the major job sectors, construction, educational services and transportation, warehousing and utilities experienced the most job gains in March compared to the same month in 2017.

“One indicator after another tells us that the vital signs of the state economy are really in good shape and are expected to stay that way over the foreseeable future,” Kleinhenz said.

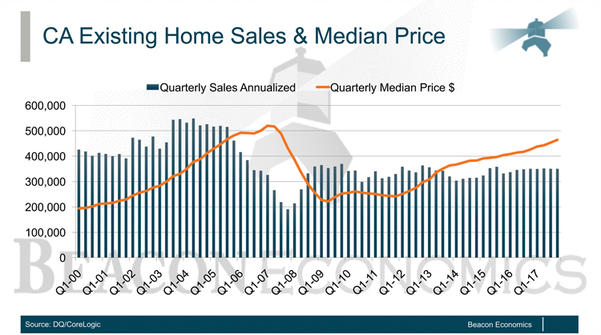

A major economic concern at the state level is the cost of housing. The median price of a single-family home in Los Angeles County increased by 8.2% from 2016 to 2017, yet there was only a 0.4% increase in the number of sales, Kleinhenz said. By the fourth quarter of 2017, only one quarter of Los Angeles County households could afford the median priced home at $604,650. This price point is still not at its pre-recession peak, however.

“We have got this economy that is putting out record numbers, and the housing market, arguably, is underperforming,” Kleinhenz said, referring to the fact that the number of home sales in the state was nearly flat from 2016 to 2017. “We should really be seeing more sales activity than we have seen. And part of the problem is that affordability is declining.”

Rents are rising, too. Many people became renters after the Great Recession, which pushed apartment rental rates up, Kleinhenz explained. “Homeownership is now and continues to be as low as it has been in about 50 years. So there is room for improvement.”

The key to improving the cost of housing in the state is to build more, he said. “In a nutshell, we need about 200,000 housing units built annually over the foreseeable future. We barely hit the 100,000 mark last year and the year before. This year, we’re maybe looking at 120,000 or 130,000 housing units,” he said. Housing for all income levels is needed, he added.

“Both renter-and owner-occupied housing shortages are going to tie our hands behind our backs if we don’t wrap our minds around and solve those problems that have persisted for really the last 25 years,” he said.

For the remainder of the year and into 2019, Kleinhenz said he expected household-serving sectors such as health care, construction and leisure and hospitality to lead economic growth in California, as well as the aerospace and defense sector.

The Long Beach Economy

Seiji Steimetz, professor and chair of economics at CSULB, gave an overview of the Long Beach economy following Kleinhenz’s presentation. He began by pointing to city demographics and worker trends, noting that only about a quarter of people who work in Long Beach live here, and only about 22% of people who live here work here.

Historically, Long Beach household income has fallen below that of the state and the county, and that continues to be the case, Steimetz noted. However, household income within the city is steadily increasing, as are wages – there was a 5.4% increase in wages for Long Beach workers in 2017.

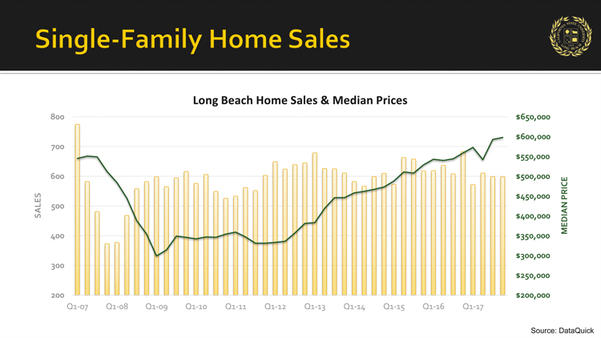

Long Beach is experiencing home price increases in line with that of the county. The median price of a single-family home in Long Beach increased by 7.1% from February of 2017 to the same month this year, he pointed out. Much like at the county level, however, home sales have remained flat since about 2016.

Local business sectors that continue to fare well include the international trade industry, with a thriving port, and the hospitality industry, which has been the beneficiary of increasing occupancy rates and corresponding increases in daily room rates charged to guests, according to Steimetz’s presentation.

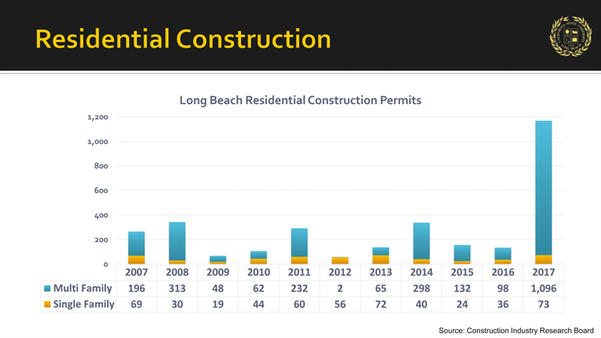

But the big news for Long Beach continues to be new construction. Permits to build new residential units shot up in 2017, according to Steimetz. “Looking at 2016 to 2017, there was a 1000% increase in nonresidential multi-family development, and a 100% increase in single-family home development,” he said.

Nonresidential construction – retail, office, industrial and other commercial development – is also on the rise in Long Beach. In 2016, $400 million worth of construction permits were issued. In 2017, $650 million worth of nonresidential construction permits were issued in the city. “Extraordinary growth. A lot of investment,” Steimetz observed. “And this large growth in residential and nonresidential construction and development begs an answer to the question, ‘If you build it, will they come?’”