Chris Acker arrived at an exciting moment: Long Beach State had just won its conference and made its first showing in the March Madness men’s basketball tournament in 12 years.

Acker, the incoming head coach, had been on the job a mere days that spring 2024 when other universities began plundering the players he inherited. Xavier and Louisville snagged two of their starters with six-figure offers.

“It was disheartening,” Acker said.

Long Beach was the only university in its conference that didn’t pay players last season, and assembled a team with less than 5 minutes of on-court Division I playing time. The season didn’t go well.

A year later, as chaos settles around college sports’ new supercharged economy of talent, a coalition of local private sector leaders has stepped in, quietly raising capital for top players in at least three sports and nudging the university to start thinking like a business rather than a bureaucracy.

Rules are now in place that allow universities and outside firms to pay athletes directly for use of their “name, image and likeness.” Long Beach State must create an atmosphere in and around the iconic Walter Pyramid stadium that people want to be part of — and must build an active and engaged donor base that supports players who can win games.

“A good team enhances the community and the city,” said Sean Rawson, co-founder of Waterford Property Company and one of the investors hoping to boost the team’s roster of talent.

Gonzaga University’s success put Spokane, Washington, on the map. Applications doubled and civic pride soared.

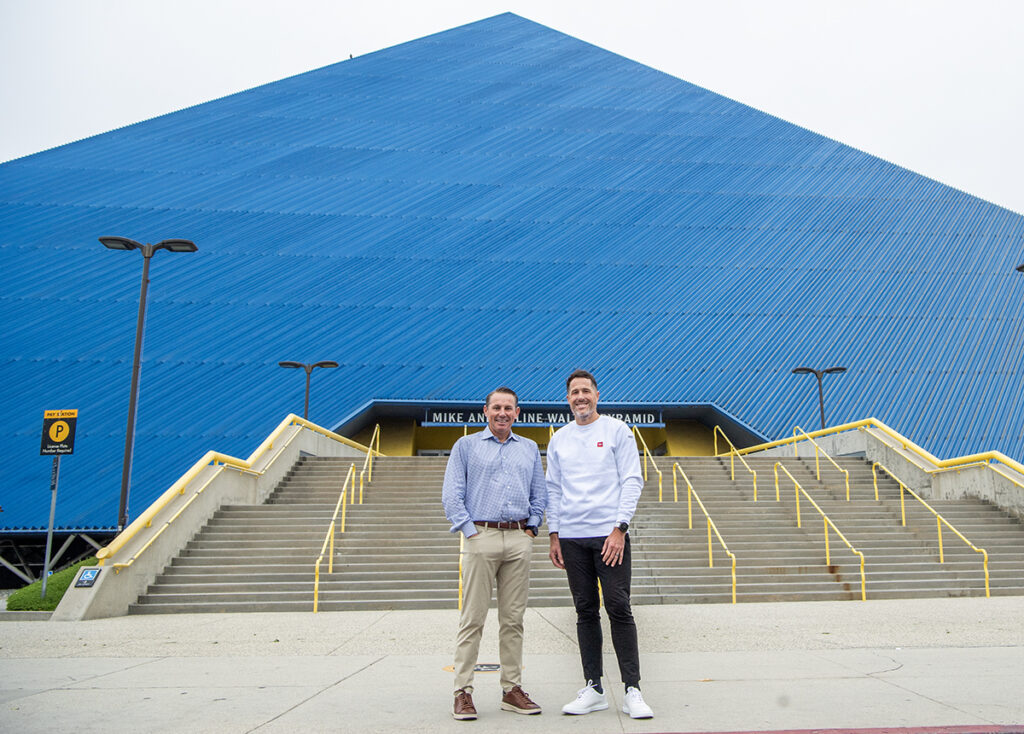

Rawson and Blake Klingeman, the COO of Curtin Maritime, who moved to Long Beach from Seattle five years ago, and others believe the same can happen here. The men’s basketball collective has committed to raising $500,000 — what Acker believed was enough to recruit a quality team this fall.

The urgency is pressing for a university like Long Beach, which plays in the top division but not in a top conference. A larger portion of the nearly $1 billion in revenue from the NCAA March tournament flows to conferences with big-name schools.

Ohio State’s athletic department budget tops $250 million; Long Beach has $52 million. More locally, UCLA has paid nearly $7 million to athletes since 2021; Long Beach State has paid just over $30,000.

The new “NIL” rules are supposed to be about “revenue sharing,” but most athletics departments in the university’s conference run at a deficit, said Bobby Smitheran, the Long Beach State athletic director for the last two years.

“In reality, there isn’t a whole lot of revenue to share,” he said.

The university is also in the midst of a major leadership transition. Not only are Smitheran and Acker both relatively new to the city, but the university is still searching for its next president.

Long Beach State doesn’t expect to come near the $20.5 million annual limit the new rules allow for total player pay.

The university is still internally getting a handle on the new rules, which just became operational July 1. Smitheran said he must also balance revenue and scholarships across 19 sports, including a national champion men’s volleyball team and the Dirtbags, the baseball team.

Confusion has also clouded the rules much of this calendar year. The Department of Education said in a fact sheet in January that universities would be required to spend NIL dollars evenly across men’s and women’s sports. Then the page disappeared.

Off campus, progress is moving more quickly. Private collectives have formed around baseball and volleyball, too, and in many cases, those involved are working together.

Acker spent the spring and summer shaking hands, networking and fundraising — among the new duties tacked on to the job description of every college coach who wants a competitive team in this new economy.

Mayor Rex Richardson has met with the coach and others involved, and said he’s on board.

“We’ve got to create a donor base and excitement to compete with teams that have been doing this a long time,” the mayor said in an interview. “It’s going to take an all-hands-on-deck approach.”

Richardson has pushed to elevate the city’s profile, particularly around entertainment. Long Beach has flirted with professional sporting teams in the past and is now pursuing a minor league baseball team. The LA Force, a third division professional soccer team, signed a deal last year to play here. Long Beach also has a long pedigree of high schoolers who have competed professionally in a range of sports.

Getting into the Sweet Sixteen — the third round of March Madness that draws 10 million viewers — would be a significant coup and windfall, the mayor said.

“There’s enormous value there,” he said.

Rawson and Klingeman’s Long Beach State Basketball Collective hosted a gathering of potential investors in July at the Boathouse on the Bay restaurant. They presented a business plan built as much on attracting top players as strengthening grassroots portals of entry — like youth basketball camps — bolstering community and business interest, and critically, enhancing and leveraging the fan experience at the Pyramid.

Rawson said one investor told him that he’d give $10,000 to the collective — all he wanted in return was to be able to easily get a beer in his courtside seat.

They are hoping to attract a range of investments for players who are still developing skills to those who could earn as much as $150,000 for their game-changing impact.

Part of their pitch is the well-documented downstream value that athletic success brings. Schools that make deep runs in the NCAA tournament receive millions in revenue, along with a boost in applications and academic interest.

Rawson, a 15-year resident, said he’s motivated by wanting to see the city and his kids experience the kind of pride a winning team can bring. He and Klingeman both have three kids under 12.

“We want to go to games and see the community come out around a great team and a great story, and have a VIP experience at a game,” Klingeman said.

They’ve also become quick friends with Acker, also in his 40s, with a wife and young daughter. The coach is hopeful about the coming season.

Thanks to financial backing, Long Beach was able to sign a crop of talented players for this year’s team, including Petar Majstorovic, a transfer from Syracuse.

Acker, who spent five years as an assistant at San Diego State and has been coaching since 2007, said his coaching style won’t change, even though money is now in the mix. He said the young men he leads still need the same qualities, both physical and mental, to play well on the court.

“All those things, discipline, hard work — they still matter,” Acker said. “Probably more so now.”

During the first week of practice in July, the screech of shoes quieted as the coach implored the players to drive the ball harder and to up their energy.

“We can’t wait for November,” he said. “We do this now, today!”

His goal is to win the Big West Conference, and he believes he has the right team — and the start of strong community backing — necessary to make it happen.