Gov. Jerry Brown signed two bills into law last week that his office touts as setting the “most ambitious greenhouse gas emission reduction targets in North America.”

Senate Bill (SB) 32 accelerates and extends the air emissions reductions standards laid out in the 2006 Global Warming Solutions Act, also known as Assembly Bill (AB) 32, by requiring the reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to at least 40% below 1990 levels by 2030. AB 32 required a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020, a goal which the governor’s office and environmental agencies indicate is on track to be achieved.

As with AB 32, the California Air Resources Board (CARB), a state agency under the executive branch, has the authority to create regulations and standards to meet those goals.

SB 32 would not have been able to pass if its companion bill, AB 197, had not also been approved by both houses of the state legislature. AB 197 adds two members of the legislature to CARB as nonvoting members and establishes a joint legislative committee on climate change policies that would “ascertain facts and make recommendations to the legislature . . . concerning the state’s programs, policies and investments related to climate change, as specified.”

While AB 197 was presented as a means to create some oversight of CARB – which, as Chris Shimoda of the California Trucking Association put it in an interview with the Business Journal, has “blank check authority to write whatever sort of regulation they want to get to the [GHG reduction] goals” – some state legislators and industry associations believe the bill simply maintains the status quo.

Richard Lyon, senior vice president of the California Building Industry Association, called AB 197 “a toothless tiger.” Upon hearing that, Long Beach’s Assemblymember Patrick O’Donnell laughed and said it was more like “a toothless ghost.” While O’Donnell supported SB 32, he did not support AB 197 because he viewed it as “feel-good legislation” that simply restated authority the legislature already has. He abstained from that vote.

The California Trucking Association had advocated for an amendment to the recently passed Senate Bill 32 which would have allowed truckers who purchased the cleanest available technologies to use them for a certain period of time without being required to upgrade as soon as something new is available. Those amendments were not included in the final adopted legislation. (Photograph by the Business Journal’s Larry Duncan).

“AB 197 doesn’t do much and should have more teeth to protect the environment and the business community in this region,” O’Donnell said. “The idea through AB 197 was to provide some oversight mechanism over the efforts to address climate change – mainly the California Air Resources Board, of which there has been much concern,” he explained.

“[CARB] came before the legislature earlier this year and they couldn’t account for the dollars they spend on each of their efforts, nor the metrics associated with each of their efforts. So CARB needs some basic accounting,” O’Donnell said. “If you have a governmental body come before you and say, ‘These are the programs we have and we can’t tell you how much money we’re spending on each program, nor the metrics associated with each program,’ there’s an issue there.”

In response to these comments, CARB’s director of communications, Stanley Young, wrote in an e-mail to the Business Journal: “CARB has responded quickly and directly to requests from the legislature with detailed information on every single project (and there are thousands of them) indicating where the money went, the estimated greenhouse gas reductions, and the specific cost-effectiveness of each project.”

Young attached a lengthy spreadsheet outlining programs aimed to reduce or mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, how much was spent on them, and associated emissions reductions. Projects and programs included developing transit-oriented housing, planting trees, upgrading landfill facilities, encouraging public transit use, replacing outdated utility infrastructure, incentives for cleaner vehicles and more.

O’Donnell expressed concern that some of CARB’s programs may be “feel-good” rather than effective. “We have a lot of emerging technologies in the port that are going to reduce emissions on ships and other port-related vehicles. . . . And CARB needs to help those technologies emerge, develop and get implemented,” he said.

In passing AB 32 in 2006, the state legislature “handed off a significant amount of authority to the California Air Resources Board,” O’Donnell noted. “Understand, that’s under the executive branch, so they don’t answer to the legislature other than through legislation and the budget.” He said the legislature shouldn’t “pass a law and then walk away,” but should “review on a regular basis how that law is being implemented and the success or failure of that program.”

O’Donnell also takes issue with CARB’s program to provide incentives to those who purchase clean-operating vehicles. “If someone is making $1 million a year, there’s no reason they should be getting a subsidy to buy a Tesla, OK?” he said. “A super majority of the residents in my district cannot afford to buy a Tesla. The number of people who can afford to buy a Tesla is infinitesimal. We should not be subsidizing the purchase of Teslas for rich people.” To be clear, the program is not specific to Teslas, although they do qualify.

In 2014, total dollars implemented for the Clean Vehicle Rebate Project amounted to $20 million. In 2015, it was more than $109 million. So far this year, more than $6 million has been spent on the program, according to documents supplied by CARB. The program website, cleanvehiclerebate.org, has a notice on the homepage that reads: “Funding is currently exhausted. All applications submitted after June 10, 2016 will be placed on a rebate waitlist.”

After delineating several places online where information about CARB’s spending is publicly available, Young concluded: “As for the type of projects the GGRF [Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund] funds, we feel that promoting cleaner vehicles and providing cleaner low-carbon transit in low-income areas to both fight climate change and clean the air are precisely the kinds of investments that California needs – and that the Legislature itself directed us to do with laws such as SB 535 that directs that at least 25% of funds from the cap and trade auctions go into disadvantaged communities.”

State’s Industries Seek Clear Instruction On Compliance

Associations representing some of California’s impacted industries indicated that while they opposed SB 32, it was not because they had a problem with reducing greenhouse gas emissions by adjusting their operations. Rather, they wanted legislators to provide more direction within the bill text as to how those emissions reductions should be reached instead of passing the baton to CARB.

After restating the goals and intent of AB 32, the text of SB 32 is quite short. It adds a section to the state’s health and safety code that reads in full: “In adopting rules and regulations to achieve the maximum technologically feasible and cost-effective greenhouse gas emissions reductions authorized by this division, the state board shall ensure that statewide greenhouse gas emissions are reduced to at least 40 percent below the statewide greenhouse gas emissions limit no later than December 31, 2030.”

A second, briefer section states SB 32 will only go into effect if AB 197 is passed, which it was. Both bills become effective on January 1, 2017.

For the state’s home builders, not having specific direction for reducing air emissions from their operations is risky, according to Lyon of the California Building Industry Association. He pointed out that the timeline for reducing air emissions as described in SB 32 is also outlined in a 2015 executive order by Governor Brown. That same order sets a goal to reduce air emissions to below 80% of 1990 levels by 2050.

“What we hear from some is that the goals are set decades ahead to give research and development and technology and innovation time to develop, and eventually show us the way,” Lyon said. “There may be some truth to that if we’re talking about things like fuel efficiency or clean car technology. But here we’re talking about residential development. We’re talking about homes and apartments and condominiums. We’re talking about retail and commercial offices, development activities, water systems, roads,” he continued. “These are all construction activities that have to undergo CEQA review.”

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) requires all development projects to undergo an environmental impact analysis before commencing. It also requires the identification of a “significance threshold” for GHG emissions that must not be exceeded. AB 32 and SB 32 do not outline what such a threshold would be in order to meet their GHG reductions goals. Therefore, the CEQA process requires developers to meet a standard without identifying what that standard is – they’re left to guess, as Lyon explained it.

“CEQA says that projects that are built today and that are reviewed under the California Environmental Quality Act are required to be consistent today with the future emissions goals,” Lyon explained. “What we have said is, we don’t know what the appropriate emission levels from our projects are. So, legislature, governor, let’s sit down and let’s determine up front what the appropriate emissions levels from our projects are and what the appropriate mitigation for those are. Just tell us the rules of the game, and we’ll do our best to do it.”

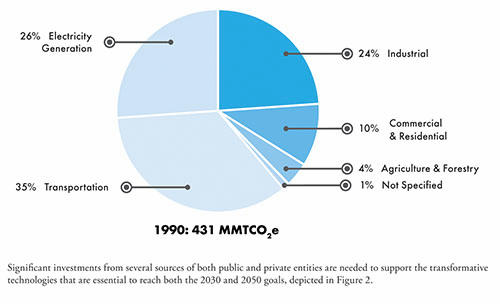

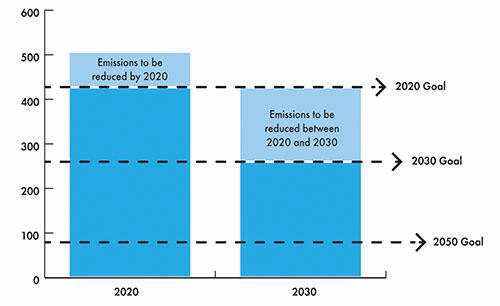

The top chart illustrates the greenhouse gas air emissions reductions goals outlined in Assembly Bill 32 (the 2020 goal), Senate Bill 32 (the 2030 goal), and a 2015 executive order by Gov. Jerry Brown (the 2050 goal). The figures on the left are measurements of carbon dioxide in million metric tons. The lower chart illustrates the greenhouse gas air emissions reductions goals outlined in Assembly Bill 32 (the 2020 goal), Senate Bill 32 (the 2030 goal), and a 2015 executive order by Gov. Jerry Brown (the 2050 goal). The figures on the left are measurements of carbon dioxide in million metric tons. (Charts from the California Climate Investments’ 2016 Annual Report)

Lyon said his industry is “stranded” as developers undergoing the CEQA process are now struggling to guess at the acceptable levels of emissions for their projects under SB 32. If it later turns out that those developers’ estimates were incorrect, “They’ll be sued,” he said. “This bill is signed in to law, and the next development project out the door – and this is not at all an overstatement – could very well be sued [because] it hasn’t designed the home or designed the transportation network or whatever it may be to meet that 2030 standard.”

The California Building Industry Association took no issue with developing a post-2020, post-AB 32 timeline for air emissions reductions, Lyon noted. But SB 32 did not provide clarity on emissions thresholds for development activity, so the association opposed the bill.

Similarly, the California Trucking Association would not have opposed SB 32 if certain amendments had been made, according to Chris Shimoda, the organization’s policy director. His association was seeking clarity about future regulations related to the use of clean technology for trucks.

“The amendments would have set an amount of time where if you bought today’s technology – the cleanest available certified by either the Air Resources Board or EPA – that there would be a certain amount of time that you would be allowed to operate that equipment before being asked to either retrofit or retire it,” Shimoda said.

The request for such an amendment stemmed from a concern that the trucking industry would be required to invest in cleaner technology and then mandated to upgrade its equipment immediately as soon as something cleaner is available. “That has been our experience over the recent past,” Shimoda said.

For the trucking industry in particular, developing technologies to meet SB 32’s GHG emissions goals is going to prove difficult, according to Shimoda. “With the state of where things are with technology and fuels, to get to the 40% below 1990 level goal we would have to stop moving trucks beginning in August and just stop running things through the end of the year,” he said. “We need some mix of fuel efficiency and advance technology to make that gap up if we’re going to be able to meet the 40% reduction goal.”

Simon Mui, director of the California Vehicles and Fuels, Energy & Transportation Program for the Natural Resources Defense Council, said that whether or not SB 32’s timeline is too aggressive “depends on the sector,” and that he believes state agencies and the legislature have the ability to “make adjustments.”

“Some may be saying it’s too quick. Others may be saying it’s not quick enough,” he said. The council backed both SB 32 and AB 197.

“There is no question that these are aggressive goals,” Mui said. “But I think to the extent that we know how to get there and we’re already doing a lot of it, it’s not like rocket science. We’re not creating something to go to the moon here. We can use existing technologies to get there.”

Asked specifically how he would respond to members of the trucking industry who say they don’t yet have the means to meet SB 32’s requirements because of a lack of advanced technology, Mui said there has been “tremendous progress” in technological development.

“To the extent that things like electric truck technologies or hybrids weren’t really in the conversation only five or 10 years ago, they are. There are companies now in California manufacturing those trucks,” Mui said.

“Just five or six years ago, people said, ‘hey, there’s nothing that could be low-carbon for the freight sector,’” Mui said. “And lo and behold, companies developed renewable diesel which is . . . not only much lower carbon but it also runs cleaner in terms of other emissions and doesn’t suffer from some of the components that are also contributing criteria in toxic pollution.”

The California Manufacturers & Technology Association (CMTA) opposed SB 32 because no due diligence was involved in ensuring that there is a cost-effective method in place for achieving the bill’s goals, according to Gino DiCaro, the association’s vice president of communications.

“For a long time, CMTA has effectively argued that a well-designed cap and trade program is the most cost effective way to get to California’s climate change goals,” DiCaro said. But there is no mention of a cap and trade program in SB 32.

Debate Over Cap And Trade Program

CARB created a cap and trade program in which manufacturers and other industry sectors are mandated against producing more GHG emissions than an allowed amount, or cap. Affected parties can purchase permits to allow their GHG-producing operations up to the cap, and they can trade permits they do not need.

While the state’s business community at large supported the premise of cap and trade – for example, the California Chamber of Commerce (CalChamber) supported it – the state’s program is now in litigation because of the way it’s structured.

CARB allocates up to half of the permits to itself and then auctions them. CalChamber is litigating this auction process, arguing it isn’t necessary for a successful cap and trade program and that it is a tax. The argument is that the auctions are illegal because AB 32 wasn’t passed with the two-thirds legislative majority required to pass a tax.

With the cap and trade program’s future in question, SB 32 should not have been passed, DiCaro argued. He also noted that under AB 32 the cost of fuel has increased by about 11 cents per gallon, and that California manufacturers in 2015 paid about 79% more in electricity costs than manufacturers throughout the country.

“The most important point is in 2015 we got 1.5% of the country’s manufacturing investment,” DiCaro said. “If you look at that at a per capita level against the rest of the states, basically any given year we are dead last, or second or third to last.”

An official statement from the Western States Petroleum Association took issue with the “rushed” manner in which AB 197 and SB 32 were passed. “The rushed vote was deliberately schemed in order to cover up today’s terrible cap and trade auction result,” the statement by WSPA President Catherine Reheis-Boyd read.

Only about one-third of available permits, also known as credits, were sold in the latest August 23 cap and trade auction.

Reheis-Boyd’s statement continued on to criticize the legislation. “Although SB 32 was rushed ahead of the results of the auction, the fact is that the passage of this measure does nothing to put the market on the right track,” she wrote. “The reality remains that SB 32 fails to address fixes to cap and trade, which sends the wrong signals to the market. Today’s miserable auction result reflects the market’s lack of certainty.”

Mui at the NRDC had another take on the results of recent auctions. “People basically aren’t needing to buy permits, these allowances, which suggests that they actually are doing fine on their own in terms of making reductions,” he said. “Some have looked at it as a glass half empty. We also look at it as a glass half full.”

Assemblyman O’Donnell said California needs cap and trade, despite the program’s recent troubles. “I think cap and trade in and of itself is a pretty hefty conversation, because I have some real concerns where the money from that program is being spent,” he noted. But he said the program is necessary, as long as the resulting funds are spent on projects that are effective.

“There has to be a partnership going forward. So if we have cap and trade dollars – if we’re charging the business community money associated with their emissions – then we need to use those to reduce emissions,” O’Donnell said.

The assemblymember indicated he wants to revisit oversight of CARB. “AB 197 was the first swing, but you know, we’re going to be back to the plate on this one,” he said. “Because it really doesn’t do much other than to say that the legislature can do what it already does. It should ensure greater oversight of the effort and funding associated with emissions reductions.”

On the subject of SB 32, which he supported, O’Donnell had this to say: “SB 32 is a positive step to further put California at the forefront of addressing climate change. We’re an example to the world. And to deny that something is happening to our climate is to deny reality.”