While residential development in Long Beach is regularly described as “booming” out of City Hall, data tells another story: Long Beach continues to fall short on housing goals amid the state shortage, especially in the “affordable” range.

But it’s not necessarily for lack of effort. The city continues to offer funding and incentives for the construction of affordable units, Development Services Director Oscar Orci said.

“It’s very difficult to get funding to build affordable housing,” Orci said, noting that it takes much longer than the process to fund market-rate housing. “I think the city’s been doing a great job at providing those opportunities.”

Despite the city’s best efforts, though, the development of affordable—and moderate-income—housing remains well below targets outlined by the state’s Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA), which projects housing needs and the number of units each city must create to keep up with that need.

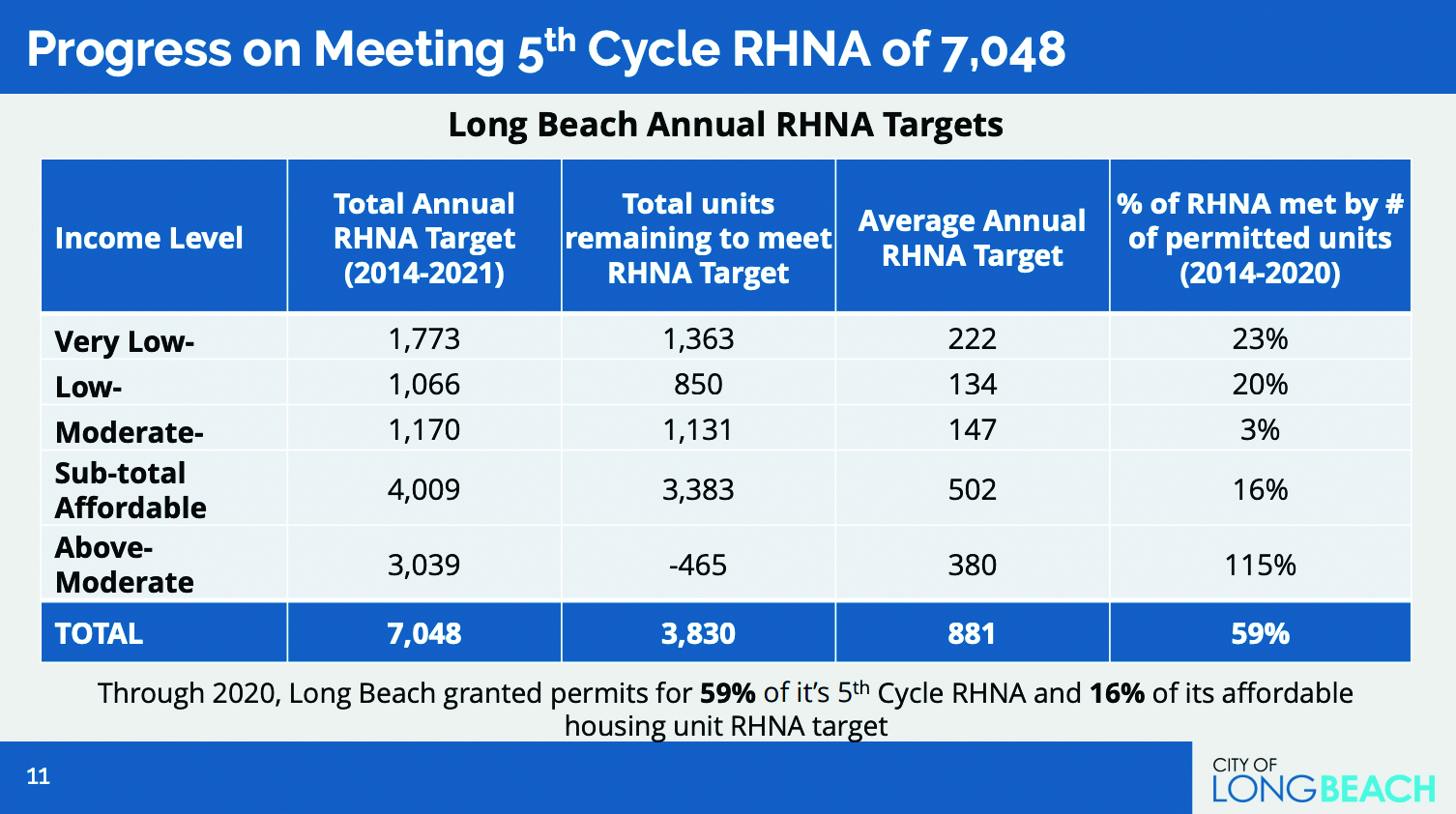

RHNA figures are updated every eight years, with the 2013-2021 cycle now coming to an end. In that cycle, Long Beach was allocated 7,048 units but only permitted 59% from 2014-2020, according to a staff presentation.

The Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG), which assigns the allocations, breaks down specific numbers by product type. Based on those figures, Long Beach permitted 115% of required above market-rate units, but less than 16% of the very-low to moderate range.

“We need housing. Period,” Orci said, noting that all types of housing—apartments, condominiums, single-family homes and accessory dwelling units—at all price levels are necessary to address the state’s worsening housing crisis.

In the sixth round of RHNA, which was approved earlier this year and spans from 2021-2029, Long Beach’s allocation increased 276%, to 26,502 units. The allocation breakdown includes 11,156 above-moderate-income, 4,158 moderate-income, 4,047 low-income and 7,141 very-low-income units.

To meet those goals, Long Beach has a lot of work ahead.

Since Jan. 1, 1,000 units have come online in Long Beach, according to city data. Of those units, 33.4% were affordable. Projects such as The Spark at Midtown, Las Ventanas and Vistas Del Puerto brought crucial housing for people with very low incomes, seniors, veterans and homeless residents in high-density areas near major transit corridors.

“Those projects look fantastic,” Orci said. “They are visually pleasing, they provide case management and other support services for that housing population.”

As of late November, however, 1,300 residential units of all product types were under construction, with only 8% classified as affordable, according to city data. Just over 19% of some 1,800 approved units in projects that have not yet broken ground are affordable.

Orci stressed that the city does not control which developers submit projects to the city, nor what types of housing those projects are. All the city can do is entice and incentivize developers to build affordable housing in Long Beach, he said.

When it comes to housing development, market-rate and luxury are the go-to for most firms. Constructing a building costs millions, especially nowadays, with soaring material and labor costs, Orci noted, so being able to ask for higher rents allows developers to recuperate their investment more quickly.

According to fixr.com, the average cost of building a five-story, 50-unit apartment in the United States is $10.5 million, with a range of $4.5-$50 million. Many of the developments in Long Beach, meanwhile, have far more units, often in the hundreds.

Government entities do what they can to offset the high costs of building. Affordable developments utilize local, state and federal housing grants, tax credits, discounted land acquisition, density bonuses, housing vouchers and other programs to ensure a project can pencil out while keeping rents low.

In Long Beach, affordable housing projects are eligible for up to $4 million from the Long Beach Community Investment Company to help projects move forward. The city publicizes a “notice of funding availability,” reviews applications and offers funding for project proposals that fit with the city’s design guidelines.

Funding for the investment company mostly comes from the federal Community Development Block Grant and HOME Investment Partnerships.

Density bonuses, meanwhile, allow developers to build more housing at a particular site than the zoning may imply—but only if the projects meet certain requirements. In Long Beach, developers can take advantage of those bonuses by building projects near major transit corridors; these bonuses are the reason Long Beach Boulevard and adjacent streets, with their proximity to the A Line, have seen much of the affordable development in the city.

And the city’s most recent push to spur more affordable housing can be found in its inclusionary housing policy. The regulation will require all market-rate projects in Downtown and parts of Central Long Beach that are submitted after Dec. 31, 2022, to include a certain percentage of affordable units—11% if the units are for rent and 10% if for sale.

The inclusionary policy applies to the Downtown area and the Long Beach Boulevard corridor south of the 405 Freeway, both of which are zoned for higher density and taller buildings. To exclude affordable units, developers can pay a premium, with that money going into an affordable housing fund.

The average apartment size in the U.S. is 882 square feet, according to RentCafe.com. With the city’s surcharge of $47.50 per square foot for each affordable unit not included, developers would have to pay an additional hundreds of thousands—or even millions—of dollars.

The city, for its part, has created a draft Housing Element, a plan that identifies properties suitable for development, development constraints, goals, policy and more. The City Council this month voted to send the plan to the state for approval. If all goes according to plan, it will return to the council for a final vote in early 2022.

Orci, meanwhile, acknowledged the challenges—and the need.

“We can always do better,” he said. “And we are trying.”