For a few days after its soft launch in May, the phones at Pusherman’s offices on 10th Street near Cherry Avenue were silent. There were no incoming orders, and no chatter on the walkie-talkie of delivery drivers picking up vapes, THC gummies or cannabis flower buds.

“The first couple of days, we got our ass kicked to be honest: zero deliveries,” said Carlos Zepeda, the cannabis delivery service’s founder. Still, Zepeda pushed forward, as he has for the past three years. For the son of Honduran immigrants, the newly-launched delivery service is the culmination of years of work to start his own licensed cannabis business.“It means the world to me,” Zepeda said.

But his path to business ownership was anything but easy.

After a failed attempt at starting a similar business in California City—Zepeda’s company ended up suing the city, alleging corruption and unfair licensing practices, but the case was later dismissed—he came back to his hometown of Long Beach in search of new opportunities.“I licked my wounds and looked at what was going on with the social equity program out here,” Zepeda said.

Not much, it turned out.

The program, which was launched in 2018 to help those most affected by the former criminalization of cannabis, has so far failed to produce tangible results, especially when it comes to increasing racial diversity among business owners in the local cannabis industry.

Zepeda identifies as Afro-Latino—which places him in two demographics that were heavily affected by the war on drugs and the criminalization of cannabis preceding California’s gradual move toward legalization. While he made it to the date of eventual legalization unscathed, he said some of his family members have spent time behind bars for cannabis-related offenses.“My personal experience is minuscule compared to what other people have been through,” Zepeda said.

Still, he believes that someone from his background owning a cannabis business can help others gain access, build generational wealth and support a movement for more equity within the industry.“For me it’s more about principle. It’s about women, Black, Brown and indigenous empowerment,” he said. “If we have wealth, we can amplify our voices, and hopefully pass and implement policies that will benefit us.”

To launch his business, Zepeda had to find a unique workaround to the city’s restrictions on a type of business that many low-income entrepreneurs say would help boost diversity: non-storefront delivery.

Currently, the city only allows deliveries from one of its 32 licensed dispensaries, all of which are spoken for already—and none of which are held by Black or Latino entrepreneurs, according to the Long Beach Collective Association. Demographic data collected by the city’s Office of Cannabis Oversight is self-reported and non-comprehensive, according to the program manager, who declined to share that data with the Long Beach Business Journal.

Applicants to the city’s social equity program have long asked the City Council to reconsider its policy on non-storefront delivery services. Its low startup costs, they argue, make delivery-only retail the most attainable business type for entrepreneurs with limited financial resources.

The cost associated with starting any of the types of cannabis businesses currently allowed in the city, from navigating the licensing process to procuring real estate in an area zoned for cannabis, is what kept Zepeda from moving forward after he first joined the city’s cohort of social equity applicants in 2019. “If you have capital, you have money, you can easily cut through the red tape,” he said, adding that many wealthier investors simply hire consultants to help them navigate the process. For him, however, starting his own business “just wasn’t attainable.”

The City Council has been discussing an amendment to the cannabis ordinance, adding licensing provisions for delivery-only businesses and shared manufacturing facilities, since last year. Adding these license types, advocates hope, will ease entry to the industry for disadvantaged entrepreneurs. The change is expected to go to council for further review in July, according to the city’s cannabis oversight office.

To work around the barriers posed by the delivery-only ban at the moment, Zepeda partnered with Catalyst Cannabis Company, which holds several dispensary licenses in the city. Catalyst CEO Elliot Lewis provided the funds to start the business, which he estimates to be around $200,000, to support underrepresented entrepreneurs like Zepeda and others in the equity program. When Zepeda approached him, he said he was ready to make a move as soon as possible.

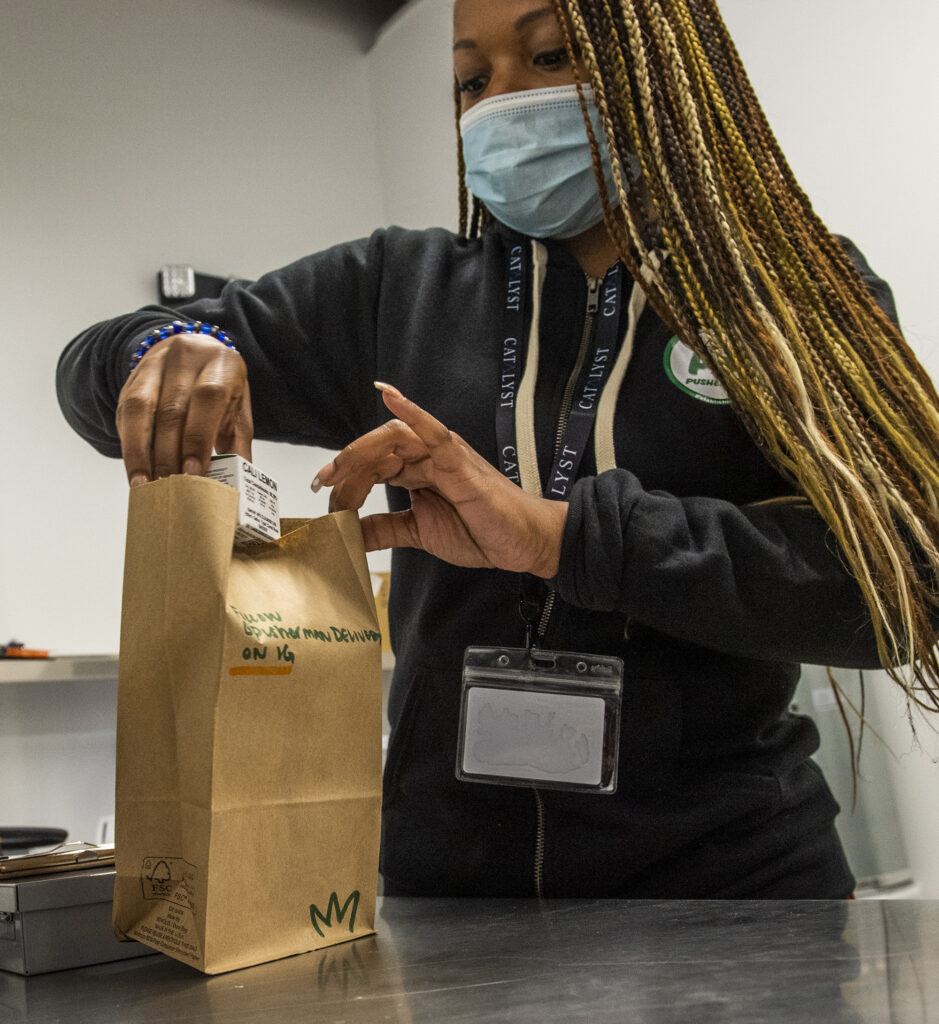

“To be totally honest, I didn’t put that much thought into it,” Lewis said about his decision to front the startup costs. “I said: let’s figure out how to do it.” His company, he noted, has placed an increased focus on social and racial equity in the local cannabis industry. “We want to be on the right side of the issue.” Jazmere Johnston, one of Zepeda’s co-founders, said that for her, the opportunity to help build a business from the ground up will be advantageous no matter where her career path takes her.

Johnston is currently in the process of applying for a manufacturing license, which she wants to use to make edible cannabis products. “I think it’s a great opportunity to learn,” Johnston said. “To put good back in our community.

”Despite the lower barrier to entry, delivery businesses aren’t without their challenges either. Only a handful of Long Beach dispensaries are currently using their license to deliver, largely because of the additional cost associated with delivery services and the high level of competition from licensed and unlicensed companies delivering into Long Beach from neighboring cities, said Long Beach Collective Association President Adam Hijazi.

Between labor costs, insurance premiums, cars and marketing expenses, “to actually run a full-on delivery, it can be very expensive,” Hijazi said. Still, he said, he supports the city’s plans to offer delivery-only licenses to lower-income applicants and those with previous cannabis-related convictions, the target demographic of the social equity program.

“For the city to be able to provide these opportunities for equity applicants is a great first step,” he said. Having more Long Beach-based delivery services is also likely to benefit licensed cannabis businesses as a whole, he noted. “The more licensed delivery you have, the more people can participate in the legal market.”

Zepeda acknowledged that building a client base large enough to make his business profitable will be a challenge, but it’s one he’s willing to take on. “This is my only avenue now, so I’m going to take what I can, make it happen,” he said. One day, Zepeda hopes to own and operate his own brick-and-mortar dispensary. “Hopefully, this is just the beginning,” he said.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to reflect that there are 32 dispensaries in the city, not 16, and also that the delivery-only licenses will go to the City Council for further review, not a vote.