Aviation and aerospace roots run deep in Long Beach—about 80 years to be exact. The sector has ebbed and flowed through the decades but has remained a constant force in the city. In the past, it was military and commercial aircraft. Today, companies have their sights set higher: Earth’s orbit and beyond.

In 1940, construction began on an 11-building Douglas Aircraft facility on what is now the 220-acre Douglas Park. Business was booming due to World War II. At one point, some 160,000 workers were assembling planes in Long Beach, including many “Rosie the Riveters.”

The war’s conclusion led to a cut in government contracts and the loss of thousands of jobs. Still, plane production continued in Long Beach under the name Douglas—bombers, Globemasters and eventually commercial airliners with the DC-8 and 9.

In 1967, Douglas merged with McDonnell Aircraft Company to form the McDonnell Douglas Corporation, which continued the city’s aerospace and aviation legacy with the production of the DC-10, the C-17 Globemaster III and more.

In the mid-1990s, Boeing bought McDonnell Douglas for $13.3 billion and rebranded its airliners. But in 2006, Boeing ceased production of its commercial craft in Long Beach, leaving only the C-17 in production in the city with a small fraction of the workforce that once pumped out as many as one aircraft every hour.

The C-17 operation was shuttered in 2015.

Though airplane production in Long Beach is gone, Douglas Park today is home to dozens of industrial buildings, several of which are adding their own chapters to the city’s aerospace history. Over the last five years, Long Beach has become a growing hub for rocket manufacturing and small-satellite launch companies.

The employment pool in Los Angeles County is highly desirable for tech companies. Long Beach, with a university of its own and its rich aerospace history, is an ideal location for these up-and-coming companies. Also, industrial real estate is virtually nonexistent across the county, particularly in the South Bay area, so the redevelopment of Douglas Park was able to draw in many companies looking to expand.

“I’m proud to see the growth that our aerospace, rocket and satellite industry has had over the last several years in Long Beach,” Long Beach Mayor Robert Garcia said. “There’s no doubt that investment in supporting this industry in the months and years ahead will help us strengthen and build back the Long Beach and regional economy.”

Here is a look at four innovative aerospace operations that now call Long Beach home.

Virgin Orbit

In 2015, Virgin Galactic—the human spaceflight and transportation arm of Sir Richard Branson’s empire—moved into its new home in one of the first phases of Douglas Park Development. In 2017, the Long Beach facility transitioned to become the home of Virgin Orbit, a new branch of the company dedicated to a new method of launching smallsats into orbit.

Virgin Galactic continues its operations outside of Long Beach.

While most rockets launch from a stationary ground platform, the Virgin Orbit team has developed a method similar to military aircraft weapons systems: the company mounts its 70-square-foot LauncherOne rocket under the wing of the firm’s Boeing 747 jet, aptly named Cosmic Girl. When the plane reaches 35,000 feet, LauncherOne is deployed, propelling itself through the Earth’s atmosphere to deliver its smallsat payload.

The company’s first launch attempt on Memorial Day last year failed because of a breach in a high-pressure line carrying cryogenic liquid oxygen, causing the engine to stop providing thrust. But Virgin Orbits’ second attempt was another story.

“It was unbelievable,” President and Chief Executive Dan Hart said in an interview. “Absolutely superb.”

Cosmic Girl’s second mission was not merely a test flight, Hart said. After much discussion with NASA, the company upped the mission’s ante and put a 10-satellite payload into its LauncherOne system.

“Scientists and students had spent years developing these satellites, so the sense of responsibility was pretty heavy on the team,” Hart said. “It was a lot of work—long hours, solving lots of problems along the way. But as the flight works out, knowing we are traveling somewhere, getting to space, it’s an incredible combination of fatigue and euphoria.

“When we released all 10 satellites in perfect orbit, everyone on the team had this incredible grin on these tired faces,” Hart added. “It was really beautiful to behold.”

With the successful launch and delivery of multiple satellites, Virgin Orbit is pushing forward, Hart said. The company has three more flights slated for 2021 and Hart said he expects to double the number of missions in 2022.

Depending on demand, Hart said Virgin Orbits’ current capability is about 20 launches per year, which is only hampered by manufacturing limitations. If demand were to exceed those limitations, Hart said, the company could tap into other resources to “easily” double production. Other than manufacturing limitations, the only other cap on LauncherOne missions is the number of times a 747 can take off each year, Hart said.

In a Jan. 18 tweet, Former Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Air Force Will Roper said the Virgin Orbit technology is “the satellite equivalent of keeping an ace up your sleeve.”

“This is a big disruptor—and hopefully a deterrent—for future space conflicts,” he tweeted.

Virgin Orbit has a wide array of contracts with various missions attached to each. The Department of Defense, NASA, the Royal Netherlands Air Force, a consortium of Polish universities and numerous other public and private organizations have all signed on with Virgin Orbit, Hart said.

Most of the company’s contracts are for missions to deliver payloads into Earth’s orbit, Hart explained. But the firm is working with one group on a potential mission to Mars and has had some discussions about a Venus mission, he said.

When Virgin Orbit was first established in Long Beach, the company had about 230 employees in one building. Since then, the firm has expanded into a second building and boasts more than 500 employees.

“Long Beach has been an aerospace center for many years,” Hart said of the company’s decision to be based in the city. “There is such talent. We have brought in a number of people right out of school or early in their career. And it’s wonderfully diverse, energetic, creative and youthful. It’s a unique place to live.”

SpinLaunch

One Long Beach aerospace company is pioneering a new method of smallsat ground launch that would literally hurl its payload into space using kinetic energy. Founded in 2014 by Chief Executive Jonathan Yaney in Sunnyvale, the company is developing a ground-based launch system that uses a large electrical mass accelerator to provide the initial thrust, propelling smallsats into orbit at hypersonic speeds.

SpinLaunch relocated its headquarters to Long Beach in January 2019, where it took over a new 140,000-square-foot industrial and office building with about 30 employees and grand plans.

“Long Beach has become an important hub for … aerospace, innovation,” Yaney said, noting that the move has allowed him to expand his company in a region where industrial real estate is hard to come by.

Over the last two years, thanks to various investors and funding sources, including a recent contract with the Department of Defense for a prototype, Yaney said SpinLaunch has quadrupled its staff as it pushes forward with development.

Yaney said his team has made strides in technology development and advancement of its launch facilities over the last year. While not ready to share details of its progress, Yaney said the company will soon be announcing milestones associated with its Spaceport America-based suborbital launch platform.

Aside from the ability to expand, Yaney said he was drawn to Long Beach because of the area’s work pool, Douglas Park’s proximity to Long Beach Airport and walkable amenities such as dining and shopping.

“[The city] has historically played a key role in Southern California’s history of aviation and aerospace and is experiencing a rebirth with New Space,” Yaney said of the industry’s recent commercialisation after years of governmental monopoly.

Rocket Lab

Long Beach’s most seasoned rocket manufacturer, Rocket Lab, was founded in 2006 by New Zealand engineer Peter Beck. The aerospace manufacturer became a U.S. company in 2013, setting up its headquarters in Huntington Beach.

But the Orange County beach city was too far removed from prospective employees in Los Angeles County, Beck said, which was a major factor for the company’s move to Long Beach at the start of 2020. Additionally, like Virgin and SpinLaunch, the company signed a lease for a brand new building in Douglas Park and was able to build out the interior to their specifications, Beck said.

While Virgin and SpinLaunch are using—or developing—new technologies to deliver payloads into space, Rocket Lab is using traditional rockets built in Long Beach and launched from land-based pads in Virginia and New Zealand. Combined, both complexes are licensed for up to 130 launches per year.

In 2017, the company launched one rocket. In 2018, three rockets. In 2019, six.

“[We were] on track to maintain that cadence in 2020 before COVID-19 led to statewide and New Zealand national lockdowns, which temporarily halted launch operations,” the company said in an email. Still, the company managed seven launches in 2020.

Rocket Launch has 12 launches slated for 2021, including a moon mission for NASA.

“The only other people who launch more than us are countries,” Beck said.

Over the course of 17 missions, Rocket Lab has successfully delivered more than 97 satellites into orbit, Beck said, including the Nov. 19 “Return to Sender” mission, which deployed 29 smallsats.

“We have a private mission to Venus and a bunch of other interplanetary missions that we get to announce soon from various customers,” Beck said.

In addition to its successful payload delivery, “Return to Sender” marked Rocket Lab’s first attempt at “first stage recovery.” After the first stage of rocket flight, a portion of the rocket separates as it enters the second phase. Rocket Lab successfully retrieved the first stage component, which represents a major milestone in making its Electron a reusable rocket and allow the company to increase launch frequency.

But 2020 wasn’t all success for Rocket Lab. In addition to the turbulence brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, the company’s Fourth of July mission that featured payloads from Canon Electronics, among others—and dubbed “Pics or it Didn’t Happen”—failed to reach orbit and deliver its payload of seven satellites. A single faulty electrical connection was determined to be the cause of the failure.

Rocket Lab has about 100 production and assembly staff in Long Beach to build its rockets and staff its mission control. But among multiple facilities around the world, the company has 530 employees.

Rocket Lab, unlike the other Long Beach-based companies, has also branched out beyond launches and is producing components for the satellites themselves. The latest addition to the satellite division came in March 2020, when Rocket Lab announced the acquisition of Toronto-based Sinclair Interplanetary.

Relativity Space

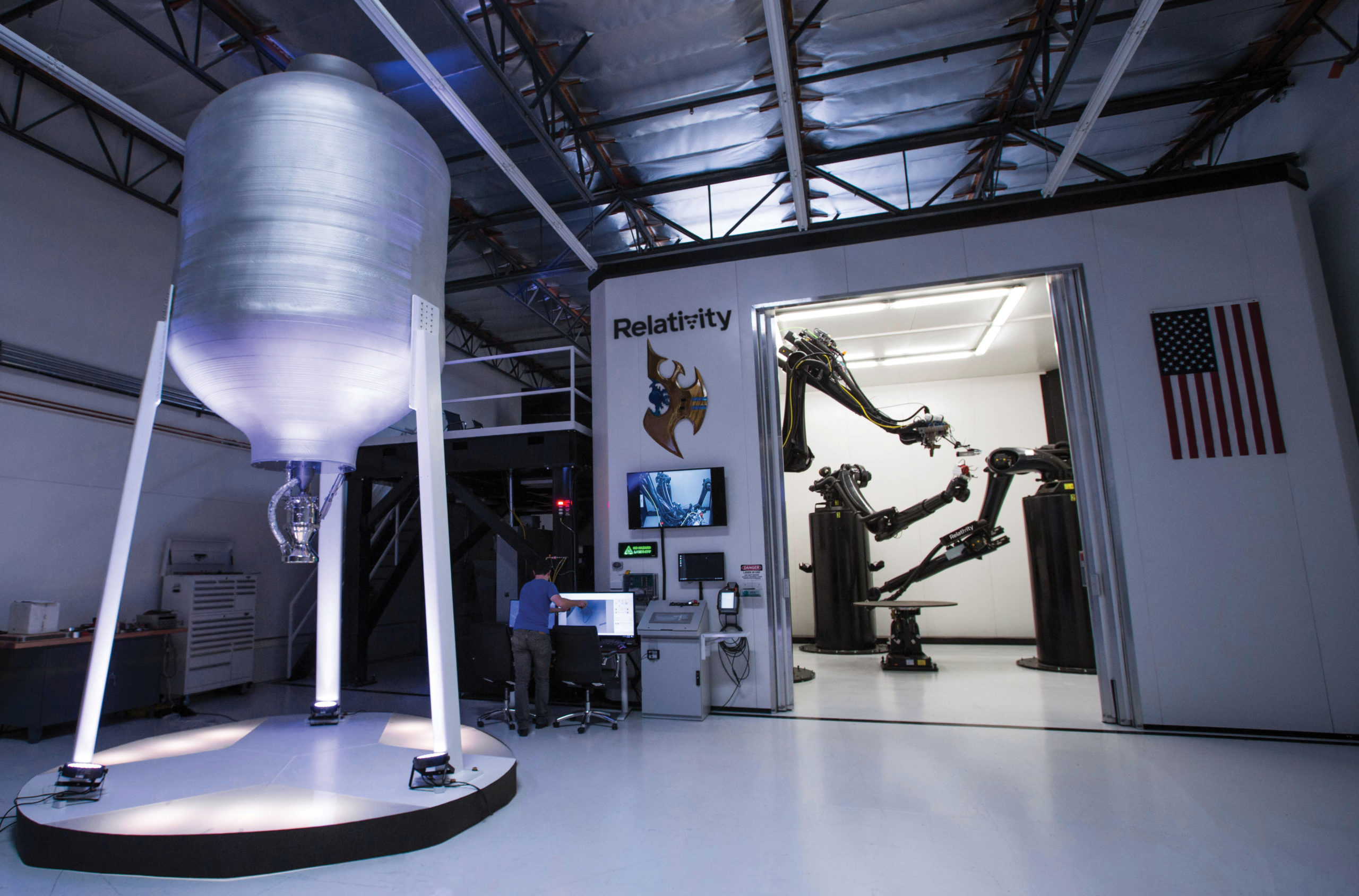

The new kid on Long Beach’s proverbial space block is Relativity Space, founded in 2015 by Tim Ellis and Jordan Noone in Los Angeles. Like Rocket Lab, Relativity is in the business of producing traditional rockets used for smallsat deliveries. But while 3-D printing has been used by Rocket Lab and the aerospace industry at large for years in parts production, Relativity has taken it a step further.

“We’re currently building the Terran 1, which is the first entirely 3-D printed rocket,” said Caryn Schenewerk, the company’s vice president of regulatory and government affairs. “We’re building humanity’s multi-planetary future.”

To print entire rockets, Relativity created Stargate, a system that uses laser beams to melt metal wire and form each component. The wire is made of a metal developed by Relativity.

Whereas Virgin Orbit and Rocket Lab’s vehicles can carry payloads of smallsats between 500 kg (about 1,100 pounds) and 300 kg (about 660 pounds) respectively, the Terran 1 is capable of delivering payloads of up to 1,250 kg (about 2,756 pounds). The rocket will still be carrying smallsats, but they will be on the larger side of the spectrum, sometimes nearly 500 kg.

Relativity is still in the development phase, with tests of its engines taking place at NASA’s Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. The company is constructing its launch site at Cape Canaveral in Florida and is slated for its first launch later this year, which will be a demonstration mission, Scherewerk said.

Schenewerk said Relativity also is working to set up a second launch site at Vandenberg Air Force Base on the West Coast within the next year.

For the next few years, Relativity’s missions will remain in the single digits, Schenewerk said. But with the capability of building a vehicle from start to finish in 60 days, she said the company will be positioned to be part of a rapid response launch, a term used by Space Force to describe rapidly deployed craft for various missions.

Sales for Relativity’s service have been “robust,” Schenewerk said, noting two recent contracts with NASA and global security and aerospace company Lockheed Martin.

The company moved into its new home at Douglas Park last summer, while the pandemic was wreaking havoc on most industries. But most of the company’s employees were well equipped to work at home, Schenewerk said, giving the company time to work on the build-out of its new facility and to bring its printers online.

The flexible work environment stemming from the pandemic, Schenewerk said, also has helped the company handle its quickly multiplying growth at its new home.

“We’ve more than doubled in size in the last year,” Schenewerk said, noting that the company has grown from around 100 employees before its move to Long Beach to around 280 now. “We’ll be in the 500-employee range by the end of this year is the expectation.”

To accommodate its growth, Schenewerk said the company is working with city officials to identify opportunities for expansion within Long Beach but would not disclose any details.

Schenewerk did say that the company is working with Pacific Gateway, Long Beach’s workforce development arm, to tap into the area’s diversity.

“We’re building rockets but we’re also trying to build a company that thinks about the inclusive future of aerospace for the workforce that is engaging in these exciting endeavors,” she said. “Long Beach has a long history of aerospace and aviation and there is a great opportunity to work with the city to continue that history.”

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story stated the C-17 plant was shuttered in 2013 and that SpinLaunch has a $45 million contract with the Department of Defense. The plant was shuttered in 2015 and the dollar amount of that contract has not been disclosed.