Crime is increasing, and it’s increasing at a rate that Long Beach Police Chief Robert Luna is not comfortable with, to say the least. To combat the surge of crime, Luna told the Business Journal he needs more resources – additional officers to make up for the cuts his department sustained during the Great Recession.

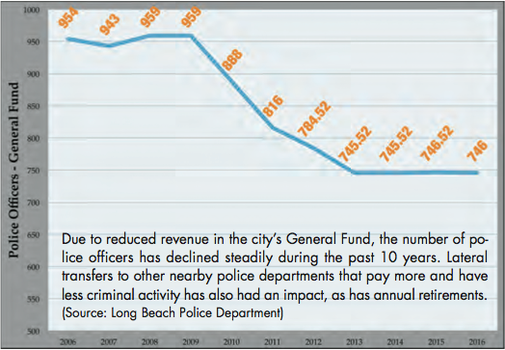

The department lost 351 budgeted positions since 2007, about 200 of which were sworn police officers, according to Luna. The remainder was civilian positions.

In 2015, violent crime increased 18.8 percent over 2014, Luna said. Property crime increased 15.4 percent. The current crime rate is still low in terms of historical averages, Luna noted, but the double-digit increase that occurred in just a year is cause for concern. “In 31 years in law enforcement, I’ve never seen this drastic turnaround or U-turn in crime stats – the double-digit increases,” he said.

Police Chief Robert Luna, pictured in his office, wants to restore his department’s South Division, which was cut due to the Great Recession. If a sales tax increase proposed by the City of Long Beach passes in June and his department receives revenues from the measure as promised by Mayor Robert Garcia, restoring the division would be his first priority. (Photograph by the Business Journal’s Larry Duncan)

While Luna said he couldn’t prove it definitively, he thinks there’s a correlation between recent legislation and increased crime in Long Beach and throughout California. “What has happened over time is you start putting Proposition 36 together with AB [Assembly Bill] 109, and then you couple that with Prop 47, and then it’s like, whoa, what just happened,” he said. “It’s almost like no one thought of putting all these together, what would happen from that perspective.”

Proposition 36, the Substance Abuse and Crime Prevention Act of 2000, allowed non-violent drug offenders to enter probationary programs in lieu of prison. Assembly Bill 109, in order to reduce populations in state prisons, sentenced non-violent, non-sexual and non-serious criminal offenders to county jail and probation rather than state prison. Proposition 47 reduced certain non-violent felonies to misdemeanors unless the defendant had prior convictions for murder, rape, sex offenses or gun crimes. The 2014 proposition applied to criminals already in the prison system, enabling resentencing and early release.

As a result of these initiatives, thousands of prisoners have been released early throughout the state, Luna said. L.A. County has the largest portion of these people, he added.

A February report from the Public Policy Institute of California analyzed data from the FBI outlining crime rates in 66 California cities with populations of more than 100,000 during the period of January to June 2015, compared to the same time period in 2014. Of those cities, 49 experienced increases in violent crime, and 48 percent had increases in property crime. Thirty-four cities experienced double-digit increases in violent crime, and 24 in property crime, the report stated.

Luna noted that crime in Long Beach began increasing around the time Proposition 47 was approved. “Sometimes somebody can make an argument with statistics and say, ‘Well, this is just one year. Maybe it’s an anomaly,’” Luna said. “Well, if you look at the first quarter of 2016, we’re actually doing worse now than we were last year. We still are [seeing] double-digit increases currently from where we were last year.”

Luna reflected, “That’s not a good sign. It’s not a good sign at all.”

In the first quarter of 2016, there were twice as many murders – eight compared to four – as in the first quarter of 2015. Overall, violent crime increased by 10.3 percent. Property crime increased by 11.9 percent.

“Different kinds of crimes are going up in different parts of the city,” Luna said. “For example, when you’re talking about some of our more violent crimes – homicide and shootings and robberies – that is predominantly in our central part of our city, the west side of our city and some portions of the northern part of our city, primarily along a lot of our corridors.”

Property crimes like burglary and auto theft are primarily increasing in East Long Beach, Luna said.

The cuts that the Long Beach Police Department (LBPD) has sustained have reduced the number of special units dedicated to proactive fieldwork. “For example, in investigations, we used to have night detectives that went out and focused on auto theft,” Luna said. “They were doing nothing but proactive work.” But then the department’s budgeted staff was decreased. “Six detectives and a sergeant, boom, went away. Their support staff went away,” he explained. “When this team [originally] came aboard, within a year that [auto] crime rate reduced significantly. When they went away, what was one of our biggest volume crimes? Auto theft. That’s one perfect example.”

Criminals are aware of the police department’s staff reductions, and what specialized units have been hit. “They do [know], because they’re out there more and they’re stealing 12, 15 cars a week, and it’s kicking our butt,” Luna said.

Another example – the gang unit. “We still have an investigative gang unit, but the field component of that gang unit, which was two different teams to cover seven days, poof, went away,” Luna said. “Is it impacting us? Absolutely.”

The police department is also being impacted by a decrease in the price of oil. Its motorcycle team specializing in traffic enforcement is funded through Proposition H, a tax of 25 cents per barrel of oil paid for by oil producers. That team is down to about eight people instead of the 16 positions it previously had.

“In 2015, our fatality traffic accidents went up about 85 percent,” Luna said. “The reason they went up is because our citations, our moving traffic violations, went down about 22 percent. . . . Unfortunately, there’s a direct correlation between traffic enforcement and both fatalities or injury traffic collisions.” Injury traffic collisions increased by 6 percent in 2015, he added.

Other factors may be playing into the increase in crime, as Luna pointed out. “In our world, jail is always a last alternative when a police officer goes out somewhere. But you have got to have alternatives,” he said. “If you think of all the massive de-investments in mental illness and substance abuse treatment over the years, and you couple that with what we talked about – letting more people out of jail – again, that’s a good argument to why crime is at double-digit increases.”

Law enforcement throughout the country is contending with public trust issues, and negative dialogue, which is likely contributing to action among legislators that may compound some of the crime problems currently worsening in California, according to Luna.

“Without pointing out specific names, if you start looking at what a lot of these people [legislators] are voting on, they are listening to the overreaction of an anti-law enforcement, anti-incarceration movement that’s happening across the country,” Luna said. “That’s what the loudest noise is out there right now, and they’re legislating to that noise.”

He continued, “Law enforcement has got very little voice right now. The pendulum’s going to swing the other way eventually. Why? Because of this: people are going to see the victims of crimes start mounting up, and they’re going to get pissed, and they’re going to say, ‘I’m tired of this.’”

What’s Needed To Combat Increasing Crime

The police department covers 25 beats within the City of Long Beach, 24/7. “We have pretty good coverage, typically, on a day. But the question that’s going to keep coming up is: do we have enough? And I’m going to tell you, we don’t,” Luna said.

“We have degraded our services so much that there are fewer officers on the street today than there have been in the last five years,” Luna said. More sworn police officers and civilian personnel are needed. Using a football analogy, Luna said he needs both starters on the field and players on the bench. “Everybody gets focused on the police officer in a black and white [vehicle] working in uniform, handling calls for service. But in order for that officer to be more effective, you need people behind the scenes to make that work so that individual stays in the field much longer.”

Luna said he hasn’t publicly stated how many police officers he needs to combat increasing crime. “I don’t believe that’s the responsible thing to do as the chief of police,” he said.

“I’ve got to be honest with you. If I had my personal choice, I’d take the 351 people I lost over the past several years, because we need every single one of them to fulfill the expectations this community has of us,” Luna said. He added that he understands the city can’t afford that – but if he were to bring the department back to how it was functioning before the cuts, that’s what he would need.

To return to 2007 staffing levels for sworn police officers – which at the step one level costs on average $148,000 [including benefits] – it would cost nearly $30 million, according to Brandon Walker, the police department’s finance administrator and acting CFO.

Measure A, the sales tax increase on the June ballot, wouldn’t come close to paying for that number of people, because the revenue it stands to generate (about $48 million per year) would also go towards infrastructure and fire needs. But it would help.

“In regards to this tax that people are talking about, how many police officers does that get us? My figures, in dealing with city hall, is about a dozen,” Luna said. “Does it get us enough? It does not. But we have to start somewhere.”

The police department’s entire South Division was lost due to budget cuts, and it’s this unit that Luna hopes to restore as a first step. Currently, that division is being covered by the West Division, and by officers from other divisions when necessary. In fact, officers dedicated to certain divisions often have to fill coverage gaps in other divisions, Luna noted.

Recruiting New Officers: Challenges And Competition

The Long Beach Police Department went five years without having any police academies to hire and train new recruits. While the police department was able to start having police academies a couple of years ago, the rate of graduation and successful retention following field training has paced only slightly ahead of losses from attrition, either in the form of retirements or lateral transfers to police departments in other cities with more competitive pay and benefits, and more attractive pension plans.

“Our attrition rate is approximately 35 [people] per year,” Luna said.

According to Luna and Michael Beckman, deputy chief overseeing LBPD’s support bureau, finding and retaining recruits is a challenge. For example, the number of qualified individuals is vastly smaller than the number that apply, and qualified recruits are often scooped up by other police departments that were either faster to hire them or offer more competitive wages and benefits. Plus, running academies strains the police department’s already-stretched resources.

The police department used to have in-house recruiters, but recruitment is now a function of the city’s civil service department, according to Beckman. “We basically support their efforts,” he said.

The applicant pool for the current ongoing academy class was 2,000 people. The pool was whittled down to 50 individuals. Since the academy started, eight people have dropped out, leaving 42.

The process for selecting academy recruits involves a written test, oral interviews, a physical ability test, an intensive background check, a psychological interview and test, a polygraph examination and a medical exam, Beckman said. After applicants have completed all these processes, police department leadership review their information in a blind process in which they are unaware of the person’s identity.

“There are several factors that are impacting our ability to recruit, select and hire, much like other agencies are experiencing,” Beckman said. “For example, the diminished number of qualified applicants who can actually get through the entire process, [and] the diminished number of applicants who reflect our diversity in Long Beach. We historically have had difficulty recruiting female applicants, people of color – both male and female – and also people from LGBT community,” he explained. “You’ll find that as a pattern at other agencies.”

On the low end, the dropout rate for an academy class is 13 percent. On the high end, it’s 43 percent, Beckman said. After recruits graduate and enter a year of probationary field training, on average about 5 percent drop out or are let go because they aren’t cutting it, according to Luna.

In Class 87, the class prior to the current academy group, there was a pool of 4,600 applicants. The academy class started with 35 recruits, and 24 graduated. Of those, 15 individuals passed field training.

Academies take approximately six months, so the police department is able to run only two per year. Each academy requires active duty police officers to step away from their ongoing duties to train recruits.

“When we run an academy, [Beckman] actually has to go beg the deputy chief of patrol and say, ‘I need three or four bodies [officers],” Luna said. “So they take four bodies out of patrol, put them at the academy to do this training, leaving four holes in patrol that the deputy chief of patrol now has to figure out now how to meet minimum staffing.” This staffing constraint is a major factor, in addition to funding, in why the department doesn’t run concurrent academies.

“Keep in mind, LAPD [Los Angeles Police Department] and LASD [Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department] have both gone on record . . . that over the period of the next couple of years they want to hire thousands of new deputies and officers,” Beckman said. “Those folks come from the same candidate pool that we’re looking at. But here’s the kicker. They’re so large, both of those agencies, that they have staff and facilities accessible where they can run academies almost on a monthly basis, whereas we can only run one or two [per year].”

Beckman noted that the length of time it takes to train and hire new police officers, as well as challenges in recruiting them, is one faced throughout the law enforcement industry.

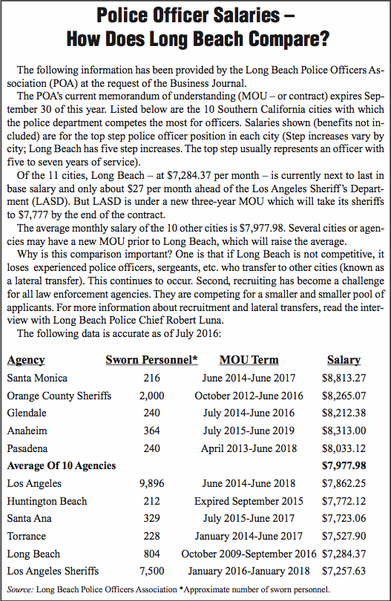

When it comes to salaries and benefits, LBPD is not as competitive as other agencies in the region, Luna pointed out, adding that this is, however, a union matter. “That’s why, unfortunately, we’re starting to lose a lot of people, because agencies around us pay more than we do,” he said. [For more information refer to adjacent chart.]

For example, “We’ve lost seven or eight people to the Anaheim PD [Police Department] recently,” Luna said. He added that there are many police chiefs working for other police departments who were former command officers or deputy chiefs within LBPD.

The way the department’s pensions are structured may deter people from other police departments to transfer to Long Beach and may in some cases also incentivize officers within LBPD to transfer to other departments.

New officers for the Long Beach Police Department receive a “2 percent at 50 pension plan” – meaning they may retire at age 50 and receive 2 percent of their top salary per year for life as a pension. Other local police agencies have a 3 percent at 50 pension plan, and officers working for those agencies would have to be bumped down to the 2 percent plan if they transferred to Long Beach, Beckman explained. In essence, this eats into the police department’s competitiveness when recruiting.

Other police departments actively recruit LBPD officers. At the recent Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach, multiple police departments, including LBPD, had recruitment booths at the event. “We actually had recruiters out there at the Grand Prix trying to recruit the people we had recruiting for Long Beach PD.… They came over and were trying to recruit our police officers,” he said.

The reduction in specialized units within the police department, as well as the reduction of budgeted higher-level positions, makes it more difficult for police officers to get promoted or move within the department, Luna noted. As Beckman put it, “There’s no where to go up.” Other police departments haven’t faced those kinds of cuts, and present more opportunities, Luna added.

“How many people do you know that have to stand before community groups like we did last week when we had four people get shot, one murdered?” Luna reflected. “And people are saying, ‘Hey, there aren’t enough of you out here. You didn’t get here fast enough. You’re not making enough effort to investigate this case. Stop the madness out here that’s going on.’”

Luna said he is not advocating for the tax initiative. But he is advocating for the needs of his police department, which are the needs of the community.