In light of Community Hospital’s closing in 2018 and subsequent plans to reopen the facility through a public-private partnership between the City of Long Beach and for-profit health care company Molina, Wu, Network LLC, members of the Long Beach City Council have proposed options to take pressure off the city’s strained emergency departments.

During the council’s March 19 meeting, 5th District Councilmember Stacy Mungo proposed the city look into community paramedicine concepts, a request that was forwarded to the council’s public safety committee for further review.

“There are a lot of community paramedicine programs taking place all over the state, and I feel that Long Beach is a model city; and I think that it’s important for all our residents, experts and leaders to have the opportunity to weigh in on what’s going on,” Mungo said.

What Is Community Paramedicine?

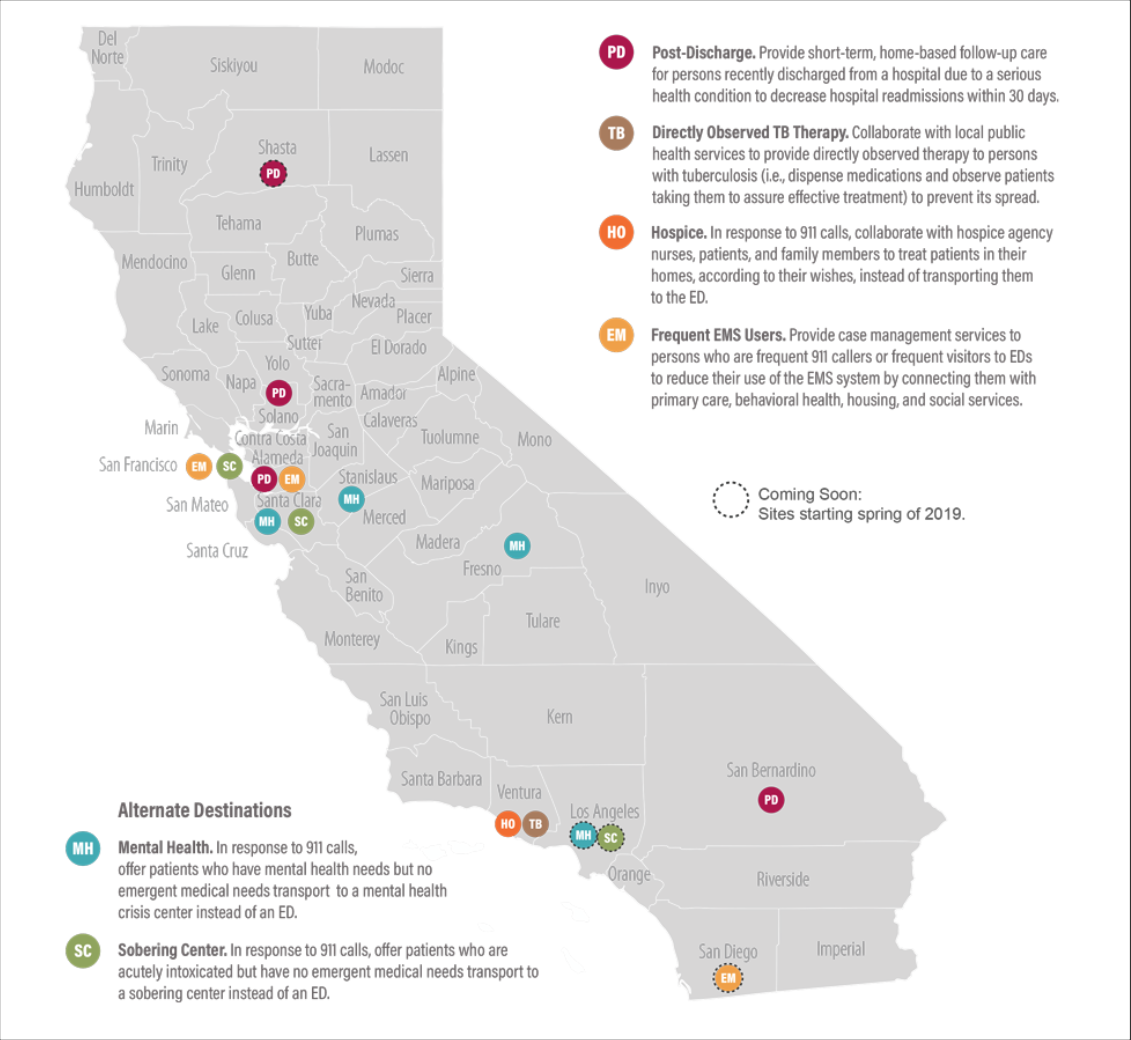

Currently, there are 12 active community paramedicine pilot projects across California, with four more projects set to kick off this spring. Spanning the state from Shasta County to the City of San Diego, the projects all have one thing in common: they give paramedics more authority.

“The old paradigm is basically: you call, we haul,” Dr. David Ghilarducci, president-elect of the Emergency Medical Directors Association of California, said of the traditional role of paramedics responding to a 911 call. Once picked up, patients are transported to the closest emergency department. “They’re often crowded with patients who probably could get better health care in other settings,” he said.

That’s where community paramedicine comes in. One concept, coined “alternate destination” seeks to expand the authority of paramedics to make a call on the spot: does the patient need to be treated in an emergency department, or would they be better served in a different environment, like a sobering center or an urgent care facility?

“We generally believe that health care is very fragmented in the United States, and that a lot of people don’t have access or know how to access the health care system. And so, they often use 911, probably inappropriately,” Ghirardelli explained. “Obviously, it has to be done safely, and a lot of patients need to go directly to the ER. There’s no doubt about that. But we think we can safely select out the few that don’t need to go there. We think ultimately it’s a more sustainable model for health care delivery.”

Alternate destination concepts, which are broken into three categories (sobering center, mental health and urgent care) are just three of the seven community paramedicine concepts that have been tested in pilot projects across California. Short-term check-ups on patients who were recently discharged from an emergency department are another concept in trial. So is linking frequent users of emergency medical services (EMS) to providers of non-emergency services that care for underlying physical, psychological and social needs.

Because these paramedicine projects are in the pilot phase, every year the California Emergency Medical Services Authority (EMSA) has to re-apply for a waiver that allows the programs to continue. This is because the “scope of practice” for medical professions is enshrined in state law and cannot be expanded without permission from the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD).

“California is one of three states that has the ability to create these pilot projects,” Sandra Shewry, vice president for external engagement at the California Healthcare Foundation (CHF), noted. “In most states, if you want to change the scope of practice for a health professional, you have to just take it into the political process immediately. California has this ability to create this safe harbor, where you can do these pilot projects, have them independently evaluated, look at the data.” According to Shewry, the other two states with similar options are Iowa and Minnesota.

Have The Pilot Projects Been Successful?

Because of their pilot status, community paramedicine projects are subject to more scrutiny than other health care services, according to Janet Coffman, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco’s School of Medicine and the lead evaluator of the community paramedicine programs under EMSA’s oversight.

“There’s 100% review of all community paramedicine visits [and] transports to alternate destinations,” Coffman said. “Each of the sites is very committed to reviewing and learning and ensuring that the care that’s provided is of high quality.”

Coffman’s research group has repeatedly reviewed data produced by each individual program to determine which have been a success, which need improvement and which haven’t worked out. “I think they’ve been pretty successful overall, with the exception of urgent care,” Coffman said.

One of the seven community paramedicine concepts that have been tested in California involves transporting patients to urgent care centers rather than emergency departments if paramedics on the scene determine their medical needs to be acute, but not life-threatening.

For example, a patient who twisted their ankle during soccer practice may still call 911, especially in the evening, when their family doctor’s practice is closed. “Urgent care can be really great for that,” Coffman pointed out. “Because you need attention pretty quickly, but you don’t need all of the more sophisticated equipment that you have in emergency departments.”

Coffman noted this is especially true for low-income patients, who may have limited access to transportation – making an ambulance the only way to access care – or a job that doesn’t allow them to take time off for doctor’s appointments. “Lower income folks do tend to end up in the emergency department a bit more,” Coffman said.

Despite the benefits of urgent care outlined by Coffman, all three projects that focused on urgent care centers as alternate destinations have concluded. “They didn’t have a lot of patients that met the eligibility criteria to be treated at the urgent care centers with whom they were partnering,” Coffman explained. As a result, only a small percentage of patients could be diverted to urgent care centers and, of those who did, many were declined or eventually rerouted to an emergency department.

The pilot project also identified a larger issue with urgent care centers as an alternative to emergency departments: they’re not licensed by the state. “So it’s not like a hospital, where you can say: if you’re licensed by the State of California as a hospital, you have to provide these certain services and any hospital should be able to provide them. Urgent care, it’s not regulated, so there’s a lot of variation,” Coffman said.

Still, she thinks urgent care centers provide necessary access to health care, especially in communities that are underserved by more traditional medical providers, like hospitals or physicians’ offices. However, to be an effective alternative, urgent care centers must offer extended hours, she explained. “For urgent care to be successful, particularly in low-income communities, you have to have night and weekend hours so that people who can’t take time off work during the day – without losing pay – still have access.”

During a Long Beach City Council meeting on April 2, 9th District Councilmember Rex Richardson asked city staff to look into incentives that could bring more urgent care services to neighborhoods with limited access to acute care facilities.

“Urgent care centers are traditionally located somewhere near emergency rooms,” Richardson pointed out. “If you look at a map of our city and where our urgent care centers exist, there are some large glaring gaps.” In an effort to close those gaps, Richardson asked city staff to come up with incentives for urgent care providers to open centers in these underserved communities and keep them open after hours to maximize utilization. “We would take a lot of pressure off our emergency rooms, if we utilized wellness preventative care and urgent care centers.”

Has There Been Opposition?

Rerouting patients to urgent care centers is not the only community paramedicine concept that has struggled in the pilot phase. A project providing short-term care to patients recently released from emergency rooms in Butte County saw the rate of hospital readmissions increase among heart failure patients, according to a February 2019 update on the pilot projects conducted by Coffman and her team. In response, the project – which is the largest of its kind in enrollment numbers – changed its protocol to provide at least one home visit per patient, the report stated. Under the previous protocol, some patients only received a phone call to follow up on their discharge from the ED.

Butte County’s increased rate of readmissions among certain patients is one reason the California Nurses Association (CNA) objects to community paramedicine, according to Stephanie Roberson, the association’s director of government affairs. “With respect to the post-discharge pilot, it hasn’t gone well,” she said. “The point of the post-discharge pilot is to reduce the rate of rehospitalization. That has not happened.”

According to Coffman’s February 2019 update, patients with chronic conditions enrolled in all five post-discharge, short-term follow-up programs showed lower 30-day readmission rates than historically recorded at participating hospitals. The report further stated that the project saved approximately $1.3 million in potential medical costs, most of which would accrue to Medicare, as well as potentially saving hospitals fees on excessive readmissions.

More broadly, Roberson said, members of CNA are concerned about the safety of their patients, mainly because they aren’t confident in paramedics’ ability to correctly assess medical needs on the spot. “No disrespect to the profession – that is paramedics and EMT– we do not believe that they have the education and training necessary to perform what we believe are primary care functions,” she explained.

Instead of rerouting patients to alternate destinations that might not be suited to treat the full scope of a patient’s emergency needs, Roberson said CNA supports efforts to set up rapid medical evaluation systems and add drug and alcohol counselors to emergency departments. “Our members obviously feel the pressure too,” she said. “But there’s got to be a way for us to institute policy that balances the health and welfare of the patient, and making sure that hospitals run in a more efficient manner. We’re all for that, but not at the detriment of our patients.”

As for community paramedicine, Roberson said CNA will continue to oppose any bill that aims to implement some or all of the concepts currently tested in California. “We oppose this across the board,” she said. “OSHPD has extended these pilots over and over again. To what end? When do we call it and say: this should not be implemented statewide?”

What’s The Future Of The Project?

If legislators did decide to implement the new scope of practice for paramedics statewide, there would still be plenty of work to do, Shewry said. “Once the scope of practice is embraced by the legislature as appropriate, there will be a whole series of policy questions that need to be resolved,” she noted. Questions would include funding sources for additional hours worked by paramedics, staffing requirements for alternate destinations and new emergency response protocols. “In terms of overcoming opposition or concern, I think it’s really [about] shining a spotlight on the data and sitting and talking with people,” she said.

For Long Beach to implement a pilot program, city staff would have to select one or several community paramedicine concepts to implement, draw up a protocol for the responding agencies and submit an application to EMSA. The application may take several months to be approved, and EMSA’s current waiver runs out in November.

Additionally, legislative efforts to move community paramedicine out of the pilot phase and change the state law on paramedic’s scope of practice are underway. “For Long Beach to file an application today, without knowing what the outcome of regulations or legislation is going to be, is a risk,” Lou Meyer, who manages the community paramedicine pilot program for EMSA, told the Business Journal.

According to Long Beach Fire Chief Xavier Espino and Health and Human Services Director Kelly Colopy, both agencies are interested in exploring their options, but have not arrived at any recommendation yet. “Community paramedicine for us is an interesting alternative, but we still need to research it quite a bit,” Espino said.

Councilmember Mungo requested a report within 120 days and said she will be meeting with residents and stakeholder on the issue in the coming weeks. “The more efficiently we can provide services and program linkages, the more we can assure tax dollars are being spent most effectively,” Mungo noted. “I’m just asking for a review of the possibilities, not necessarily proposing any one of them at this time.”