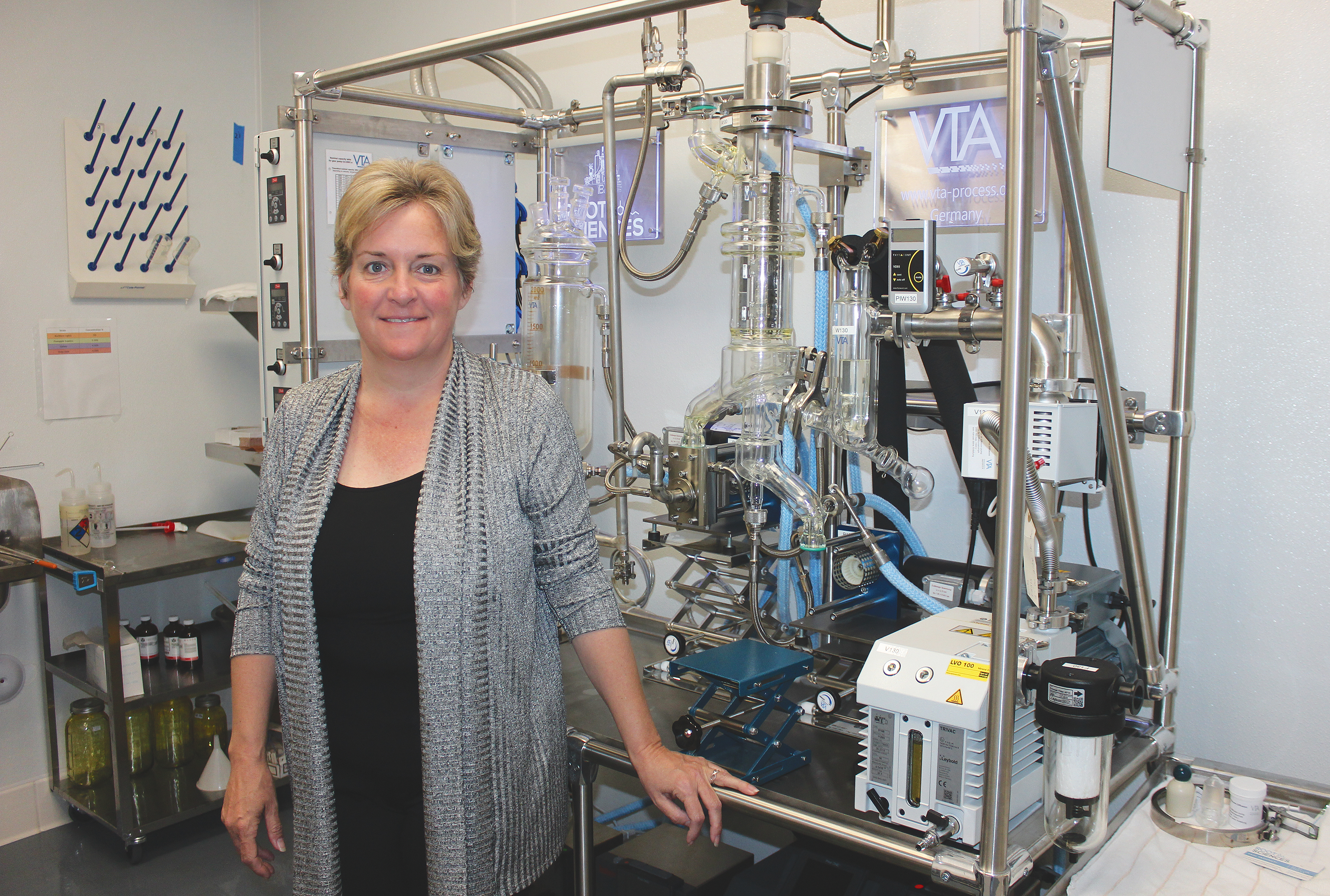

With stainless steel countertops, high tech equipment and the occasional can of cake pan spray, Stacy Loucks’ TKO Edibles is open for business. But recently, TKO has been struggling. Before the legalization of recreational cannabis in January 2018, the company, like many of its peers, operated in a legal grey zone.

Since becoming a fully-licensed, legal manufacturing business in the City of Long Beach on December 24, 2018, TKO Edibles hasn’t produced a profit, Loucks explained. State and local taxes as well as facility and packaging requirements have driven down margins. “It’s dramatic, because our margins are so much smaller now. Regulation has made everything very expensive,” Loucks said.

Now, the Long Beach Collective Association (LBCA) and individual cannabis businesses are lobbying the elected officials to reconsider the city’s 6% tax rate on the gross receipts of manufacturing and distribution businesses in the industry. If taxes remain the same, they say, Long Beach stands to lose two of the industry’s most profitable sectors altogether.

“For Long Beach, there’s a huge opportunity to benefit from the booming cannabis industry, and they’re just going to miss out on it if they’re not competitive and they don’t provide an environment where cannabis businesses can thrive,” Omer Saar, president of the Feelgood Sales Group, told the Business Journal. Saar’s company submitted an application for a distribution facility in Long Beach that is still pending. For now, Feelgood has opted to use a location in Los Angeles instead. Just a few miles to the north, the City of Los Angeles offers a 1% tax on distribution and testing, and a 2% tax on manufacturing.

Cliff Harrison, co-owner of the largest dispensary in Long Beach, The Circle, said he had initially planned to add distribution to the cultivation and retail facility, but decided against it based on the city’s tax rate. Instead, they also use a distribution facility in Los Angeles. “Although it’s a big inconvenience, we chose to use the distribution out of the other city because of the huge tax burden here,” Harrison said, adding that he would reconsider plans for distribution from Long Beach if taxes were lowered.

In Fiscal Year 2018, the city reported no tax revenue from distribution and only $500 in revenue from manufacturing. Licensed manufacturing businesses are required to pay a minimum tax of $250 per quarter. In 2018, just one business paid this fee over two quarters. In FY 2019, the first full fiscal year of legal adult-use cannabis, the city is expecting to take in $22,250 in tax revenue from these two industry sectors, assuming successful applicants and current license holders start and continue operations. This figure is dwarfed by the $2,329,341 in revenue dispensaries are expected to bring in during the same time frame.

Businesses like TKO Edibles, those in the distribution and manufacturing sector of the cannabis industry, can produce a groundswell of tax revenue for cities. Dispensaries handle small volumes of product at a high value. Additionally, the total number of dispensary licenses in Long Beach is capped at 32. Distribution facilities handle high volumes of product to be sent to numerous dispensaries in cities across the area and pay taxes on their gross receipts. “The distribution businesses are the largest revenue-generating businesses,” Richard Lambertus, chief operating officer of Seven Point Management, told the Business Journal.

Lambertus and Saar are part of a group that has lobbied city staff and elected officials to review tax rates, building requirements and licensing processes that they say place an undue burden on certain sectors of the industry. “There’s some things that just don’t make sense,” Saar said. Both described their interactions with city staff as pleasant, and said the city’s licensing department did what they could to help businesses through the process. But, they say, a lack of knowledge about the industry and the number city departments involved has made the licensing and approval process tedious.

“The city has had some difficulties understanding some of the complexities, specifically related to cultivation,” Lambertus said. But it’s not just cultivators. Saar said some building requirements on distribution facilities pose a security risk. Mandated windows have been a major sticking point for businesses across all sectors of the industry. “You’re required to put a window in a distribution facility, where the window has no function,” Saar explained. “It’s actually a problem, because now people are seeing into a cannabis business that’s a sitting duck for being robbed.”

Cannabis businesses have to comply with a number of state requirements placed on all commercial buildings, as well as regulations specific to the industry and local ordinances. During its April 9 meeting, the Economic Development and Finance Committee of the Long Beach City Council discussed the option of a 24-month pilot program “to expand the tax-base on non-retail cannabis businesses by streamlining processes, adjusting tax rates, and providing incentives.” In addition to reviewing local regulations and policies, 5th District Councilmember Stacy Mungo suggested the city might lobby to change regulations in Sacramento. “The requirements have been burdensome,” she noted.

In a unanimous vote, the committee asked city staff to study the feasibility of a 24-month pilot program, including a review of tax rates in other Los Angeles County municipalities, and present their results to the city council within 30 days. “Folks are in the pipeline, they want to invest here, they want to create jobs. For some reason, the process is slowing them down,” 9th District Councilmember Rex Richardson said during the meeting. “There’s economic opportunity here. We have some goals in terms of tax revenue; let’s exceed them.”

Richardson also pointed to the city’s Cannabis Social Equity Program, which was designed to “address the long-term impact that federal and state cannabis enforcement policies have had on low income communities in the City of Long Beach,” according to the Office of Cannabis Oversight’s website. Richardson pointed out that because of the low staffing levels necessary to operate a dispensary, opportunities for employment and social equity largely rested in the remaining sectors of the industry, such as cultivation, distribution and manufacturing. “What I’d like to see is us take a look at the reasons why these businesses haven’t taken off,” Richardson noted.

Loucks said she was supportive of the social equity program, but has been forced to automate her production process to cut costs. “We couldn’t afford to have as many employees,” Loucks said. “We have this great social equity program in Long Beach and the whole idea is to hire people from the local area, give them jobs, give them a living wage, and we can’t.”

Local entrepreneurs are urging the city to move quickly or risk losing out permanently. The facilities necessary to distribute and manufacture cannabis products at a large scale are expensive to set up, and once settled, businesses are unlikely to move their operations somewhere else. “If you lose the distribution and manufacturing businesses, they’re not coming back,” Lambertus warned.