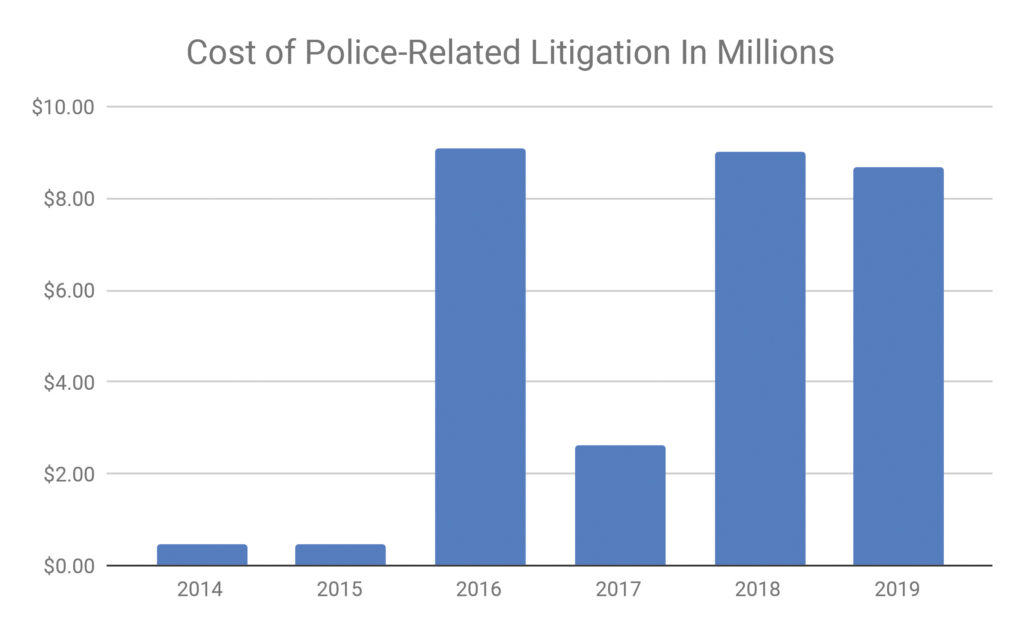

In the past five years, the City of Long Beach has spent at least $30.3 million on litigation related to officer-involved shootings, police use of force and in-custody deaths, according to data provided by the city attorney’s office. This total does not include staff salaries and the cost of outside counsel or experts hired by the city. A vast majority of this total cost, which includes payouts on verdicts and settlements, as well as attorney’s fees awarded to plaintiffs, was accrued between January 1, 2016 and August 1, 2019.

The cost of police-related litigation totaled less than $500,000 in 2014 and 2015, respectively, before soaring to over $9 million in 2016. Since then, costs have remained in the millions each year.

This is due, in part, to higher verdicts issued by juries in recent years, according to Long Beach Police Commander Erik Herzog and City Attorney Charles Parkin. While it’s hard to pinpoint exactly why juries have awarded higher dollar amounts in recent years, both Herzog and Parkin have formed theories based on their experience with cases litigated by the City of Long Beach.

Parkin’s staff often speaks to jurors after a verdict has been issued to better understand the factors that influenced their decision. “Juries are becoming more sophisticated,” Parkin noted. “They look at how many shots were fired, and they may say: we think the first two shots were OK, but shots three and four were not.”

Herzog suggested that emotions have played an increasingly important role in court, leading to higher payouts, a flame he believes to be fanned by attorneys looking for their cut on a profitable settlement or verdict. “Look at some of the payouts for traffic accidents: juries are just giving a lot of money based on emotions now. It’s not just our industry,” Herzog pointed out.

Cases involving allegations of police misconduct or excessive use of force by police officers often involve a lot of difficult emotions, Deputy City Attorney Howard Russell told the Business Journal. This, he noted, is especially true for officer-involved shootings that have resulted in a person’s death. “It’s very, very difficult for everybody in the process,” Russell said. “The family members who have lost a decedent as well as the officers. They don’t go to work in the morning planning to take a life.”

As mandated by court and in the interest of avoiding a million-dollar verdict, the city attorney’s office attempts to settle cases, offering plaintiffs a certain amount to settle their case. The dollar amount offered in settlement negotiations is calculated based on previous settlements and verdicts in similar cases, and any offer over $50,000 has to be approved by the city council. “Officer involved shooting cases can be difficult to settle because of the numbers involved,” Russell explained. “The plaintiffs themselves – the people, not their attorneys – read the papers and see big verdicts and big settlements and think: I want that for my loved one, too.”

Of the $30.3 million in verdicts, settlements and attorney’s fees awarded in police-related cases against the City of Long Beach, $21.8 were awarded in cases of officer-involved shootings.

Throughout the litigation process for each case, the city attorney’s office has a challenging line to walk. Settlements can reduce the financial harm incurred by the city, but can be perceived as an admission of guilt by the officers involved, Parkin said. “They feel as though we don’t have their back, we’re not defending them,” he explained.

“The primary [question] is always: do we think our officers did the right thing, based on the law and based on policy? And: what’s best for the city?” Russell said.

It is difficult to draw conclusions on police conduct by comparing annual payouts or measuring up the cost of settlements and verdicts to the City of Long Beach against the cost incurred by other cities, Russell noted. “There’s a lag time between when the event happened and when the trial takes place,” he explained. “If a shooting happened today, it probably wouldn’t end up in front of a jury for a year-and-a-half to two years, at a minimum.”

Three of the five cases in which litigation concluded this year were filed based on incidents that took place in 2016. The remaining two pertained to incidents that occurred in 2017. In the past five years, the city attorney’s office has been involved in litigation based on incidents going as far back as 2009.

The demographics and political leanings of an area also impact potential verdicts, Russell noted. Juries in more conservative communities may issue lower verdicts in cases related to police conduct, he explained. “If you compare just the awards, the dollars awarded, Orange County is going to be less than L.A. County as a rule, San Diego County is probably going to be less than Orange County,” Russell said.

As a result, Herzog said, the Long Beach Police Department (LBPD) doesn’t change its policies solely based on the cost of litigation incurred by the city in a specific case or year. “We don’t look so much at the payout, but we are constantly looking at: how can we fix our tactics, how can we fix our training? How can we continue to improve and evolve?” Herzog explained.

At times, however, individual cases do change the practices and policies of the LBPD, Herzog noted. He referenced the case of Marcella Byrd, a 57-year old African American woman diagnosed with schizophrenia, who was shot and killed by LPBD in 2002, after reportedly stealing a cart full of groceries and flashing a knife at responding officers.

“That changed how we [act] as a department,” Herzog said. “Over the years there are numerous examples of ways we’ve looked to get better based on [feedback from] the community, and not just in our community, but things that have happened in other agencies.”

As a result of the Byrd case, LBPD now sends out mental evaluation teams (METs) to incidents involving suspects with potential mental or behavioral health challenges, Herzog noted. METs consist of an officer who has received special training in dealing with these kinds of situations as well as a clinician from the L.A. County Department of Mental Health.

In addition, officers now receive additional training in de-escalation and communication techniques and a wider range of non-lethal equipment such as pepper gel or rubber bullets. Additionally, officers have access to behavioral health services themselves, Herzog said. “If we want our officers to treat people right, we have to treat them right as well,” he explained. “It’s been very successful in our department. We have a lot of officers reaching out.”

Despite these efforts, a case that bore a striking resemblance to Byrd’s case recently resulted in a $9 million verdict against the City of Long Beach. This was the largest verdict ever issued against the city in a police-related case, according to Russell. A jury awarded this record amount in the case of Sinuon Pream, a 37-year old woman with a history of mental illness who was shot and killed by LBPD officers following an altercation during which she reportedly “brandished a knife,” according to a report compiled by the L.A. County district attorney’s office.

The county attorney’s office found that the officers “acted in lawful self-defense and defense of others.” Parkin said his department was surprised by the size of the verdict. “We talk to the police department about it and try to, as best we can, learn from those [cases] on a go-forward basis,” he said. But, he noted, “if the police officers followed the policies and the procedures, and did everything right, we should be defending our employees for doing the job they’re supposed to be doing.”

A new California law, Assembly Bill 392, creates new standards for police use of force, effective January 1, 2020. “Stephon Clark’s Law,” named after an unarmed 22-year old African American man who was shot and killed by police officers in Sacramento in 2018, requires that police use deadly force only when “necessary.” Previously, state law had allowed the deployment of deadly force by police officers when deemed “reasonable.”

Herzog said his department has already implemented new policies to comply with this stricter legal standard and is currently working on new training materials to prepare officers for the change. “Well before the law even got signed, we knew things were coming down [the pipe] and we’ve been proactive in trying to monitor that and update some of our use-of-force language to meet that [standard],” Herzog noted.