When the coronavirus spread to the U.S., millions were forced to stay home from work and school. With little notice, colleges and universities nationwide were forced to shift their learning models to a fully digital space.

The transition, at first, seemed temporary. But as colleges and universities have worked through the challenges to build a system that allows for learning exclusively online, officials now say remote instruction will likely become a permanent fixture of higher education.

The early difficulties that professors and administrators faced in implementing such a major shift, though, were real.

“Pre-pandemic [online] offerings were minimal at best,” Lee Douglas, vice president of academic affairs at Long Beach City College said. “It wasn’t really that widespread.”

The transition to 100% online instruction was challenging for students, Douglas said, as well as educators. “It was, I’ll be very honest, a traumatic experience for many.”

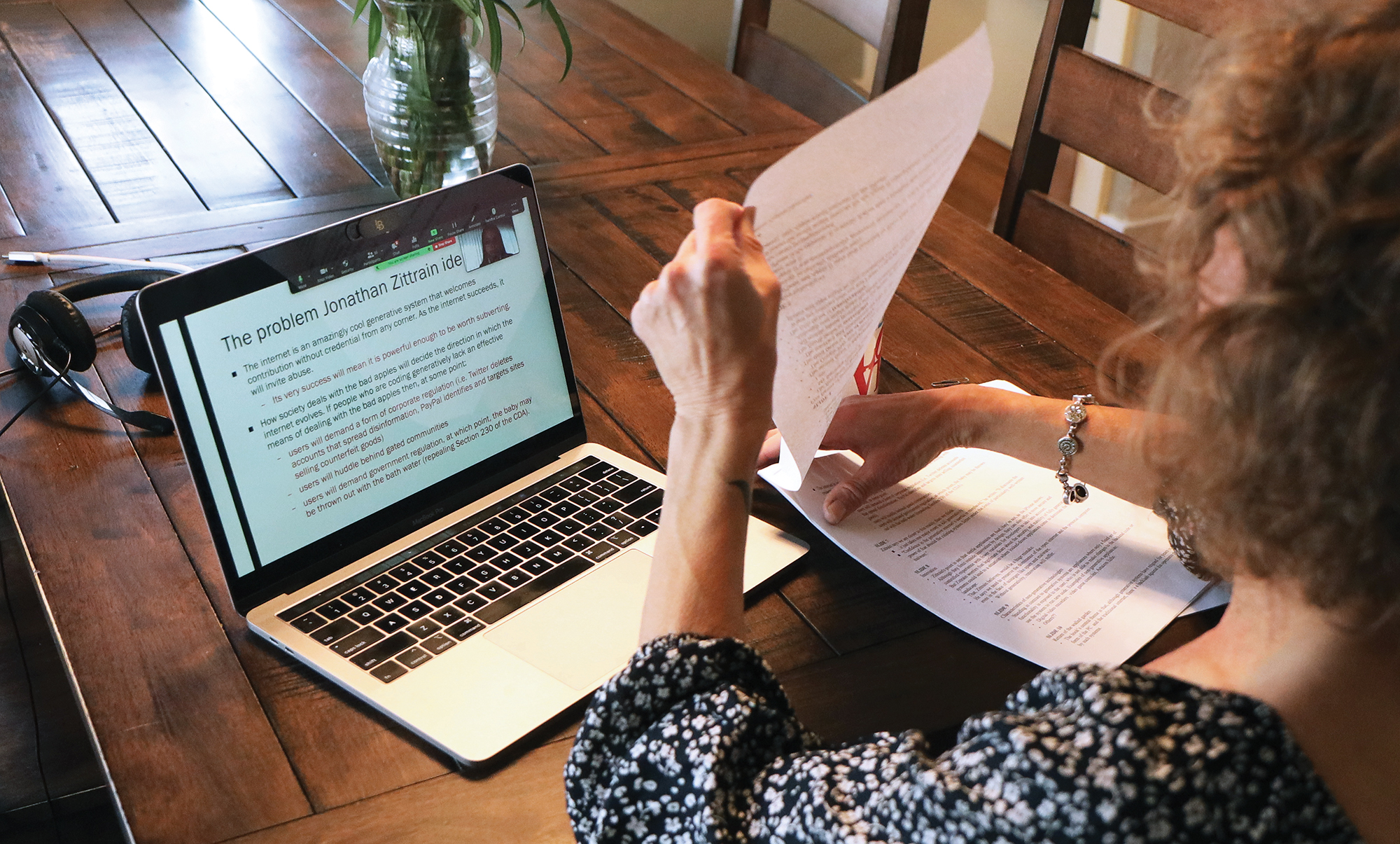

Prior to the pandemic, William Jeynes, a professor of education at Cal State Long Beach, said he assumed his lack of experience with teaching online put him in the minority. However, when the school set up Zoom tutorials for teachers, he quickly realized the vast majority of his colleagues were as new to the format as he was.

Another assumption Jeynes had, “and it turned out to be wrong, is that in terms of technological ability, my students were ahead of me,” he said. “Many of them were, but what surprised me is how many students I had to assist technologically.”

Despite the early challenges, both educators agree there are many benefits to online learning. The primary benefit amid the pandemic, of course, was the ability to continue teaching students during a time of turmoil that kept people physically apart.

Another major benefit of online education is the flexibility provided to both students and teachers, Douglas said. Prior to the pandemic, asynchronous online classes (those without set meeting times) were the most common form of online class. Before and during the pandemic, the asynchronous format allowed students to learn at their own pace, on their own schedule.

“Many of our students are working, they’ve got family responsibilities—they just have full lives,” Douglas said. “The opportunity to take online classes allows them to … take care of those responsibilities, and still complete their educational goals.”

Even synchronous online classes (those with fixed meeting times) provide more flexibility for students and faculty by eliminating travel time, Douglas noted. For students at Cal State Long Beach, commutes often include frustratingly extensive searches for a parking spot, Jeynes said.

On the flipside, the digital divide among students became more apparent amid the pandemic and the shift to a virtual education, Douglas said. Many students lacked the technology required for online learning, including laptops, tablets or regularly accessible Wi-Fi.

“Clearly, there are some homes that are higher in socioeconomic status than others,” Jeynes said, adding that the issue is close to his heart having been raised in New York’s inner city by his single mother.

“I’m concerned they’re placed at a greater disadvantage than they would be if they were simply doing in-person classes,” he said.

Schools from elementary through college took steps to address technological inequalities by providing thousands of students with items free of charge. Cal State Long Beach, for example, received $5 million in CARES Act funding to purchase laptops, tablets and hotspots for students.

But even when you account for the digital divide, the online format still hasn’t been a panacea. It does not lend itself to various types of classes, particularly those that require hands-on training and experience that cannot be gained virtually such as the trades, sciences and nursing, Douglas said. These classes are often much smaller and continued to meet during the pandemic, with proper safety measures such as masking and distancing, he added.

Based on the continued demand for online courses, Douglas said the benefits clearly outweigh any challenges as far as students are concerned. Two years into the pandemic and the course breakdown at LBCC is about 50% in person, 50% online, he said.

Douglas said it is hard to know what to expect in the future, but he is certain demand for online courses will remain well above pre-pandemic levels. As it is, online courses fill up faster than in person classes, he said.

“I would say we’ll likely end up at 55% face-to-face, 45% online,” Douglas said. “But we’re monitoring what the students are saying to us with their registration. Many have gotten accustomed to the online learning environment.”

At Cal State Long Beach, Jeynes said his students have made it clear there is high demand for online courses. He said he hopes the administration gives up any notion that the university should return to the previously normal mix of the vast majority of courses only being offered in person.

“It’s an unrealistic goal,” Jeynes said. “All these students have experienced online as a result of COVID and … we’re going to have more students who prefer online than before. If we don’t go with the trend, we run the risk of being left behind.”

Long Beach City College is actively encouraging teachers—for in-person as well as online instruction—to utilize Canvas, an integrated online tool used by dozens of colleges across the country. The platform allows students to stay up to date with their grades and assignments and allows for the integration of various tools for students and teachers alike.

Cal State Long Beach recently began the transition away from its in-house platform, BeachBoard, to Canvas. Early adoption of Canvas began this semester, with all courses being on Canvas by fall 2023, according to the university website.

“The model that called for universities to develop their own software, in a lot of cases, led to really interesting tools being developed that weren’t supported for the long term,” Canvas Senior Director Ryan Lufkin said. “By going with a third-party vendor, you get the benefit of not only cutting edge tools that are constantly being improved, but they’re also supported long term.”

Since the onset of the pandemic, adoption of Canvas by universities has quadrupled, according to Lufkin.

Early in the pandemic, the shift online was rudimentary, with many teachers attempting to “shoehorn” the traditional classroom experience into the virtual space, Lufkin said. But after a year of primarily online learning, teachers have begun intentionally designing lessons for the digital environment, including having assignments, materials and tests built into the virtual classroom and leveraging engagement tools such as discussion boards, Lufkin said.

“The bar in technology-enhanced learning has been raised, probably for good at this point,” Lufkin said. “We continue to add features and functionality.”

Canvas was built with an open architecture, Lufkin said, which makes plugging in other products such as Zoom a seamless process.

Aside from adopting platforms like Canvas, colleges and universities are taking steps to encourage the broader use of virtual learning. One area LBCC is examining is the integration of technologies into the classroom that allow for classes where some students are physically in the room while others tune in remotely, Douglas said.

“That technology is available and we’re looking into a couple different [ones],” Douglas said. “It allows us a great deal of flexibility in terms of how we offer instruction.”

Flexibility has become a part of many people’s lifestyles, Lufkin said, which will continue to drive demand for virtual—fully online and hybrid—courses permanently moving forward.

Jeynes, for his part, said he was very strongly against online learning prior to the pandemic, but his experience over the past two years has transformed his view. While he is still opposed to asynchronous online classes, he said the online format has been a pleasant experience for his synchronous courses.

As far as students’ grades are concerned, Douglas said the shift online has not had a negative effect.

“One of the fears was that students would not succeed in an online environment and that our course success rates would fall,” Douglas said. “But we’ve not found that to be true. It’s almost equivalent.”