Craig Beck, the newly appointed director of public works for the City of Long Beach, and Sean Crumby, deputy director and city engineer, visited the Long Beach Business Journal office to answer questions about infrastructure needs. One question focused on technology and innovation, which has a price tag of $70.6 million for “critical infrastructure related to technological advancement, public safety, disaster recovery and ongoing cyber security needs.”

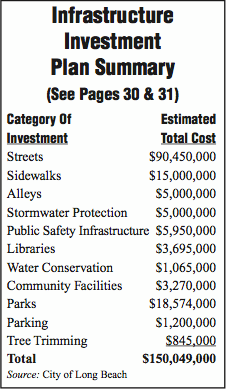

(Click here to download a list of how the first $150 million collected from additional sales tax revenue, if Measure A passes in June, would be spent.)

“Why is $40 million of that $70.6 million set aside for ‘handheld radios for public safety?’ That doesn’t make sense. How many radios do we need?” Beck and Crumby were asked.

Beck replied: “The FCC [Federal Communications Commission] required the city to go to a different frequency. They took away our frequency and forced us to a new bandwidth. So we have to change our whole communications [system].” The change has been in the works for years and is directly associated with first responders being able to communicate with one another and with other agencies during an emergency.

Pictured is Lewis Street in California Heights. Many of the streets in the that neighborhood look similar to the above, and the sidewalks are no better. (Photograph by the Business Journal’s Larry Duncan)

The Business Journal staff quickly realized with that answer that unfunded mandates from the state and federal government represent a considerable portion of the city’s infrastructure costs. For example, the fire department lists 33 infrastructure items totaling nearly $125 million. Twenty-four (24) of them are associated with government mandates, including station upgrades due to Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requirements.

In fact, most residents are unaware that of the 300-plus items totaling $2.8 billion in capital improvement program needs, a majority of the improvements are triggered by unfunded mandates or code changes. In other words, city staff has no choice but to follow new requirements from agencies such as the Air Quality Management District and the Regional Water Quality Board, or from laws or regulations such as Assembly Bill 1881 (the water efficiency state code), AB 32 (reduction of greenhouse emissions) and the ADA. Beck stressed that of course staff wants to make all the changes, many of which target quality of life issues, but that sufficent money is not available.

Beck stressed that it’s important for residents to understand that currently there is very little money in the General Fund for infrastructure. It’s the General Fund that pays for public safety, libraries, parks and recreation, etc. Much of the capital improvement budget is “segregated” into various funds such as Tidelands or Gas, he pointed out. Money in those funds is restricted. “That’s always a difficult message to deliver to the community as a whole . . . I think there’s somewhere in the neighborhood of 60 different funds in the city,” Beck said.

He said that if voters approve the tax measure, all of the money raised from the increase goes directly into the General Fund. Instead of $6 million as is budgeted for infrastructure in the current fiscal year, the General Fund will be $50 million or more annually over the next six years, and half that amount for the following four years, allowing staff to chip away at the lengthy list of projects. (For a better understanding of how the money is “segregated,” review the adjacent “Sources of Funds 10-year snapshot” provided by Beck.)

A year ago, March 24, 2015, the city completed and submitted to the city council a “State of Our Streets” assessment that examined every inch of major and local roadways in the city – 768 miles worth. In order to bring all the streets to an excellent condition, it would take $420 million in 2015 dollars, according to the report.

Unfortunately, due to a lack of money, it was one of only a few assessments completed. The tab for the street assessment was $1 million, which equates to a mile of street that could have been paved. “I’m a big proponent of planning saves you money, but it’s one of those things we have to weigh constantly,” Crumby said. Beck noted, “It’s hard to get council to say, ‘Here’s a million dollars go do a plan’ instead of ‘Here’s a million dollars go fix the street.’”

“It’s common for cities to do facilities master plans, too,” Crumby cited as another example. “Long Beach does not have a current facilities master plan that would go and assess all the roofs in all the facilities and structures. That’s something that we need to do as well.”

In lieu of a thorough assessment in each of the infrastructure categories, staff has provided its best estimates to arrive at the $2.8 billion amount. That, along with public safety issues, led Mayor Robert Garcia to propose the sales tax increase. Whether the infrastructure cost estimate is 10 or 20 percent higher or lower is irrelevant since the tax will raise only roughly $400 million over its 10-year history – far from what is needed.

Another major asset that needs to be addressed are the city’s bridges – more than 100 of them. The estimated price tag? $365 million [government funding may be available to cover part of the cost]. It’s not just structural issues; ADA regulations impact bridges as well. Beck noted that the Davies Bridge, the bridge on 2nd Street at the south end of Naples, “is in real bad shape. If you park underneath it by the Boy Scout area, there’s concrete falling from the bottom of the bridge.”

Crumby stated that “code compliance constantly changes. . . . ADA is a prime example for that. As the law evolves, we have to do more. If bridges haven’t been touched for 20, 30, 40 years – the laws were different back then. We need to have wider sidewalks, the slopes change, all of those things change.”

Beck added: “I remember in 1990, when the city first put together an ADA plan, it was roughly $40 million in need. We have more than $40 million just in sidewalk cuts in the city today.”

When government alters regulations, it can significantly impact costs, as illustrated with the following example concerning the city’s storm drains.

An estimated $292 million is needed for storm drains, which have requirements attached through the 1973 Clean Water Act. But according to Crumby, the Act “wasn’t effectively enforced or mandated until about 10 years ago.” Cities must obtain a clean water permit by developing a master plan program. Long Beach recently received its second such permit. Crumby said costs for the program “are shooting through the roof. We used to only be concerned with getting water off the streets, and getting it in to rivers, or bays or beaches. That’s still a priority, but when the water gets there, it has to be clean. So we have to clean all the water. . . . the whole program is rapidly changing.”

The duck pond at El Dorado Park, which uses more than 6.4 million gallons of water, is one of the items in need of repair. According to city officials, the pond is a health hazard and is leaking. The pond is among the items listed for repair on the first $150 million raised from the tax measure. However, the city has applied for grant money through the Water Quality, Supply and Infrastructure Improvement Act of 2014. City Engineer Sean Crumby said the city is “aggressive” in going after grants for infrastructure needs. The city may know this month if the $1,754,000 grant request is approved. (Photograph by the Business Journal’s Larry Duncan)

Last year, according to Beck, the permit issued by the Regional Water Quality Control Board cost the city $785,000. This year it’s $1.2 million. That’s just one permit for one program in one city department imposed by a state or federal agency. But there’s more about how state and federal mandates continue adding costs to cities.

When the city received its first permit, it was required at that time to put filters in all the catch basins. “So we went and spent a bunch of money on putting filters on all the catch basins,” Crumby said. “We spent money on maintenance, cleaning these things out, and so on. The second permit comes out and now they don’t like filters. They want treatment devices at the outlets. We’re still going by the filters because we haven’t put in the treatment devices.” The changes came from the water quality control board. When asked if the boardmembers just keep changing their minds, Crumby responded, “It’s evolving. Just like the ADA, it’s constantly evolving.”

As far as prioritizing the more than 300 infrastructure projects, Beck said, “When you see the list, when you see what’s on the list, I don’t see anything that isn’t a priority.”

He added: “Part of municipal government’s responsibility is to address community needs. There are a whole lot of interest groups in Long Beach, and what we’re trying to do is address a portion of those interest groups. We may not be able to do a brand-new park, but at least we can do some park facilities, or we’re able to do some dirt alleys, certainly not all. We’re doing our best to touch on these categories. I don’t have an alley assessment, but I can tell you a dirt alley is the worst.”

What’s Beck’s take on the tax measure? He explained the need this way: “Long Beach is well over a hundred years old and she is starting to show her age, and I think we’re looking to see an infusion to bring Long Beach back to the glory that it used to be.”