With mega ships hauling considerably larger cargo volumes, the San Pedro Bay ports are facing new challenges of having to load and unload containers faster and more efficiently than ever before to prevent massive congestion.

Among a multitude of ways to potentially solve this problem, one idea is to develop an “inland port,” a concept that has been around for nearly a decade and which is now being seriously reconsidered by stakeholders, according to international trade experts and port officials.

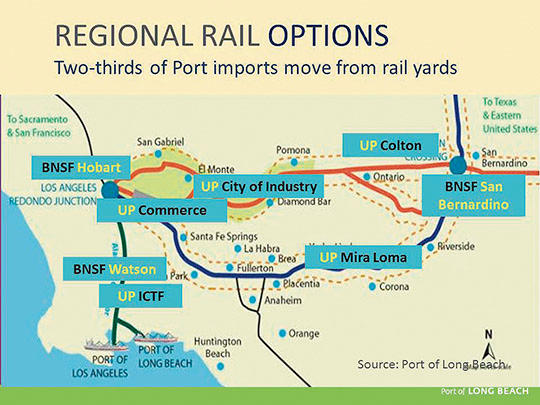

(This map, provided by the Port of Long Beach, shows rail options throughout the Southern California region, with two thirds of imports moving through rail yards. According to industry officials, an “inland port,” if justified for using short-haul rail service, would have to be centrally located in the Inland Empire, either in San Bernardino or Fontana.)

Though there are various versions of inland ports throughout the country, the main premise locally is to develop a logistics center in the Inland Empire, expanding distribution and warehousing operations miles away from the local seaports.

Cargo containers would be shuttled there by short-haul rail, sorted and then distributed throughout the region. Likewise, such facilities would energize inland markets by creating a direct connection for inbound and outbound cargo.

The main benefit locally is that it would make the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles more competitive and efficient by alleviating congestion and reducing truck trips on local highways.

Still, for such a plan to move forward, the business case would have to be made that an inland port is not only needed but that it would be financially beneficial for all parties in the supply chain. Other considerations would also have to be taken into account, such as labor costs, environmental impacts, jurisdictional limitations and land use restrictions.

The last time stakeholders took a serious look at the inland port concept was in 2008, when a report for the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) found that the idea, although plausible, was unwarranted at the time.

The report concluded that, although an inland port would have benefited the local region, “efforts required to overcome the implementation barriers wouldn’t be justified, especially when the region has other, more pressing needs for goods movement resources.”

However, a lot has changed since then, said John Husing, an economist who specializes in international trade in the Inland Empire, and who has recently been hired to conduct a new study on the feasibility of developing an inland port.

“It’s an idea that’s been reactivated and a serious look is going to be taken at it,” he said.

The key reason the concept is being revived is that imported cargo containers are not only being shipped in larger quantities on larger ships but are also being stowed differently, changing the way terminals digest container flows, said Mike Christensen, senior executive lead in supply chain optimization for the Port of Long Beach.

“It’s almost like a tsunami of unsorted boxes compared to the relatively measured flow of containers that came out of the smaller vessels,” he said. “So we’re having to look at every option of how we can make this supply chain work more smoothly.”

B.J. Patterson, CEO and president of Pacific Mountain Logistics, LLC, a warehousing and distribution company in Ontario, said developing an inland port might now make financial sense as larger cargo volumes have the potential to cause major congestion and a truck driver shortage.

“I think up to this point it’s been very difficult to make the economics of it work, but now we’re getting to a volume that appears that we have got to do something to relieve the congestion at the port,” he said. “Particularly with the issues with driver capacity and not having enough drivers, we’re going to have to do something to increase the competiveness of the inland areas, and I think the best way to do that is probably an inland port.”

Patterson, a member of the International Warehouse Logistics Association (IWLA) and the Distribution Management Association (DMA), said that industry representatives are considering locations in Fontana or San Bernardino for an inland port that would be centrally located in the Inland Empire.

Tom O’Brien, director of research at the Center for International Trade and Transportation (CITT) at California State University, Long Beach (CSULB), said there are inland ports functioning in other parts of the country but whether they are successful and make financial sense really depends on the type.

In Texas and Chicago, for instance, cargo handling facilities that bring “value-added services” to inland locations at crossroads of trade lanes in rail or truck corridors, have been “fairly successful,” he said. However, the concept of merely “moving port operations out further” is more challenging, O’Brien said.

The main drawback to such an inland port in the past has been that moving cargo twice or “double loading” comes with added costs, creating trade-offs in the supply chain.

“You can eliminate some very congested areas if you move your activity out,” he said. “But are you increasing turn times for trucks? Are you increasing costs moving the goods in time of the market? Those are all part of the equation.”

One of the costs associated with an inland port is labor, O’Brien said.

While building an inland port would create more jobs in the inland area, dockworker union members may argue that they have jurisdictional authority over the work, he said. It’s unclear whether union representation could be expanded. On the other side, shippers might find it more beneficial to handle goods outside of the port to reduce labor costs.

Another obstacle is convincing inland community members that building warehousing and distribution facilities, which would add rail and truck traffic, would be beneficial to them, O’Brien said.

“In some cases there is going to be strong community interest in where the facility is located and how much truck and rail traffic it generates,” he said.

Also, rail lines, which already have thin profit margins, would have to commit to investing in short-haul service, Christensen pointed out.

Union Pacific and Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) Railway, the Port of Long Beach’s Class 1 rail partners, both derive their revenue from long-haul service, which offsets the costs of the more expensive short-haul trips, he said.

While the port has budgeted $1 billion toward rail infrastructure upgrades, with only 20 percent allocated, most of the funds are going to increase on-dock and near-dock rail capacity and other local rail infrastructure projects. Investing funds outside of the port would be a bit more challenging, Christensen said.

An inland port could be financed, however, through a public-private partnership, he said, adding that such a financial arrangement would be more complicated and would take a strong justification for private equity to come into play.