Federal research has concluded that drug prices are increasing. And perhaps unsurprisingly, liberals and conservatives are at odds over what to do.

Congressional documentation shows that the cost of Mylan’s EpiPens, a life-saving injectable form of epinephrine that stymies allergic reactions, has increased by more than 500% in the past decade. The cost of insulin, a generic drug crucial for treating diabetes, more than tripled between 2002 and 2013.

After the drugs Isuprel and Nitropress, which are used to treat heart conditions, were purchased by Valeant Pharmaceuticals International Inc. in 2015, their costs increased by 525% and 212%, respectively, overnight. In 2015, Turing Pharmaceuticals LLC purchased a drug used to treat parasitic infections, which are deadly for AIDS patients and pregnant women, and raised the price from $13.50 per pill to $750.

Legislators are asking why.

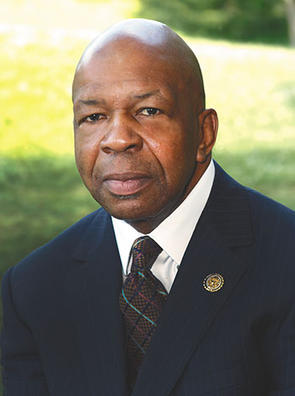

Primarily led by Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Elijah Cummings, Congress has for the past several years been leading the charge to investigate price increases of medicines crucial to the health of the American people.

In a statement to the Business Journal provided by the press department of the U.S. House of Representatives, Cummings said: “Congress cannot continue to sit on the sidelines while drug companies take advantage of American families. Time and time again, we have seen companies hauled before us, but they ignore our outrage and never lower their prices. Now is the time to take decisive legislative action to curb the rising costs of prescription drugs and stop drug companies from bilking the American people.”

Cummings, who is the ranking member of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, has called to task executives from companies like Mylan, Turing and Valeant, who each subsequently announced price reductions, generic drug versions or rebates for their drugs.

Rep. Elijah Cummings is the ranking member of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. He is an advocate for transparency in pharmaceutical costs, and believes drug companies are “bilking the American people.” (Official photograph courtesy of U.S. House of Representatives)

In the case of Valeant, a memorandum from the committee dated February 2, 2016, indicated that CEO Michael Pearson “purchased Isuprel and Nitropress in order to dramatically increase their prices and drive up his company’s revenues and profits.”

The memo continued, “The documents obtained by the Committee demonstrate that Valeant identified goals for revenues first, then set drug prices to reach those goals. Valeant employed this strategy for both Isuprel and Nitropress, generating gross revenue of more than $547 million and profits of $351 million in 2015 alone. In contrast, Valeant’s research and development expenses for Isuprel and Nitropress were ‘nominal.’”

Key takeaways from the September 21, 2016, hearing on the rising price of EpiPens by the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform were, according to the committee’s website, that “the ACA [Affordable Care Act] has exacerbated the costs of prescription drugs as consumers shift to high-deductible plans,” but also that “a lack of transparency exists in the drug-pricing market and Mylan’s finances and figures did not add up under scrutiny.”

Another takeaway was there is a lack of competition for epinephrine injectors, which is necessary to lower costs. “FDA could not reveal how many applications for new entrants into the epinephrine auto-injector market are pending or how long those applications have been in process,” the committee’s webpage states.

In 2015, at the request of Cummings and Sanders, the U.S.Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) inspector general investigated sudden price hikes by generic drug manufacturers. The resulting report, released in December 2015, was titled “Average Manufacturer Prices Increased Faster Than Inflation For Many Generic Drugs.”

From 2005 to 2014, “For the top 200 generic drugs, 22 percent of the quarterly AMPs [average manufacturer prices] exceeded their inflation-adjusted baseline AMPs,” the report found. However, a previous report analyzing the cost of generic drugs between 1991 and 2004 found that a higher number – 35% of reviewed quarterly average manufacturer prices for generic drugs – exceeded the inflation-adjusted baseline for price increases. So there has been a 13 percentage point improvement in this area since the last report.

Sharon Jhawar, Pharm.D., corporate vice president of pharmacy for Long Beach-based SCAN Health Plan, wrote in an e-mail to the Business Journal, “Drug prices have risen an average of nearly 10% over the 12-month period in May 2016 – a time when the overall inflation rate was just 1% in the U.S.” She continued, “The irony here is that these ballooning drug prices have come at a time when Big Pharma is under more scrutiny than ever from consumer watchdog groups and American lawmakers.”

Jhawar noted the increase is in part due to the introduction of specialty drugs to the market. As reported by the Business Journal last year, Gilead Sciences Inc.’s hepatitis C drugs Sovaldi and Harvoni, which cure hepatitis C in most patients, cost more than $1,000 per pill. Treatment plans total $84,000 to $175,000, depending on the individual.

According to Jhawar, specialty drugs account for 33% of all drug spending in America but are used by just 1% to 2% of all patients. “According to a study published in the ‘Journal of the American Medical Association’ in August, for each person in the United States, $858 was spent on prescription drugs, compared with an average of $400 per person across 19 other industrialized nations,” Jhawar wrote.

In recent years, elected officials at the state and federal levels have put forth legislation designed to give the government oversight or negotiating power in the price of pharmaceuticals. Many of those efforts have failed.

According to a spokesperson from the U.S. House of Representatives, Cummings has introduced various bills aimed at improving the cost of drugs for Medicare Part D beneficiaries, requiring drug companies to report price increases exceeding 10% to DHHS, shortening the exclusivity period for biologics from 12 to seven years, and others. None were passed by the House.

Introduced in 2015, Cummings’ Prescription Drug Affordability Act would, according to a spokesperson, “improve Medicaid and Medicare, enhance transparency, encourage competition, and make prescription drugs more affordable for everyone.” The bill still has not come up for a vote.

In California, the recent ballot initiative Proposition 61, which was backed by Sanders, would have restricted the price state agencies could pay for drugs, tying the amount to what the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs pays. The proposition failed.

In August, California Sen. Ed Hernandez removed his drug price transparency bill from consideration after it was amended in the state assembly. “I introduced SB 1010 with the intention of shedding light on the reasons precipitating skyrocketing drug prices,” he said in a press release at the time. “The goal was transparency, making sure drug companies played by the same rules as everyone else in the healthcare industry. Unfortunately, recent amendments have made it more difficult for us to accomplish our fundamental goal.”

In January, California Assemblymember David Chiu, who represents the east side of San Francisco, yanked his proposed Pharmaceutical Cost Transparency Act from consideration by the state legislature when it became apparent he didn’t have enough votes to support it. The bill would have required pharmaceutical manufacturers to file a report with the state for drugs costing more than $10,000 per course of treatment.

State Assemblymember David Chiu authored legislation, which he yanked from consideration earlier this year, that would have created transparency for the highest priced prescription drugs in California. The bill did not get enough support from his colleagues in the state legislature. Pharmaceutical companies have the ears of many legislators, he believes. (Official photograph courtesy of Assemblymember Chiu’s office)

“I introduced a bill in the context of enormous price increases in many drugs across the spectrum, the most notable example being the drugs that treat hepatitis C,” Chiu told the Business Journal. “When I first came into office two years ago, Gov. Jerry Brown had to propose a $300 million increase for hepatitis C drugs that cost $1,000 a pill – close to $100,000 for treatment, retail. And the $300 million increase to the budget for that one drug alone would have only helped about 3,500 patients in a state where we’re seeing three-quarters of a million Californians at some point in the future being afflicted with hepatitis [C].”

Chiu called his proposal modest. “My bill would have only applied to the most expensive drugs – drugs that cost more than $10,000 a treatment – and asked pharmaceutical companies to help us understand the basic cost structure,” he said. “The industry tells us that their drugs are priced high because they need to recoup their research and development costs. Studies we know of show that the pharmaceutical industry spends 19 times as much on marketing and advertising as they do on research and development.”

Chiu continued, “And so we wanted to understand for those companies that produced the highest-priced drugs, . . . what were their aggregate research and development costs? What did they spend on manufacturing? What did they spend on marketing and advertising? And what were their profit margins?”

The pharmaceutical industry has opposed and defeated every solution to the rising cost of prescriptions that have been proposed, Chiu said. When asked if the industry has the ear of many of his colleagues in the state legislature, he said, “Absolutely.” He also pointed out that the pharmaceutical industry spent $130 million to defeat Prop 61.

Other governments, including some with regulated health care systems that negotiate prices with the pharmaceutical industry, have far lower costs for prescriptions, Chiu pointed out. In Great Britain, for example, the cost of curative hepatitis C drugs is about a third of the cost in the U.S., he said.

“I am open to a wide range of options,” Chiu said. “I think that drug manufacturers need to work with all of the other stakeholders in health care to figure out how we clamp down on costs.”

Chiu reflected, “I think, short of government controlling the price of pharmaceutical drugs, transparency would go a long way at shedding light on what’s really happening and allow policymakers and the public to make informed decisions in the next round of policymaking to address drugs.”

Some in the medical community believe that government is not the solution to rising pharmaceutical costs, but that it is the problem. Dr. Thomas LaGrelius, a Torrance-based concierge physician, is a self-described “free marketeer” who takes this position. He is president and chair of the National Concierge Physicians Professional Association and has served as president of the local Los Angeles County Medical Association chapter and as a delegate for the California Medical Association. He visits Washington, D.C., twice a year to meet with leadership from the House of Representatives to advise them on health care policy.

“The federal government is involved in all the pharmaceutical problems, and they have created millions of pages of regulations that you can’t even read,” LaGrelius said. “I mean, it takes an army of attorneys to get anything done in the United States anymore. We need to eliminate regulations that are creating difficulties for people to quickly start a competing company to make EpiPens at a quarter of the price they’re being sold for by the only one that makes them.”

Because epinephrine injectors like the EpiPen can be manufactured as generic drugs, someone will eventually step in and fill the consumer need for a cheaper, generic version of the drug, LaGrelius said. “I assure you, someone is going to be making EpiPens much cheaper very soon if government lets them,” he said. Strict government regulations are the main roadblock to this happening, he argued.

“If we had a free market that worked like we used to, none of this would exist. Prices would be low,” LaGrelius said.

Specialty drugs like Harvoni and Sovaldi are priced high because they cost an immense amount to research and develop, according to LaGrelius. But their high cost is also due to the relatively short patent time for drugs allowed by the federal government, he argued. “What I would do as a free marketeer is I would extend those patent times way out so that the pharmaceutical industry could recover their investment over a period of 50 years, rather than 10,” he said. That, he contended, would lower costs for consumers.

“Very few people understand how a market economy works. And it’s the only kind of economy that works,” LaGrelius said. In contrast, regulated economies like the Soviet Union never work, he added. “We were headed that direction very rapidly. Now we have a chance – a chance, a slim chance, in my opinion – of turning that around if Trump actually sticks to his guns and the Republicans actually have some cajones. We’ll see.”

Within President-elect Donald Trump’s proposed health care reform, outlined on DonaldJTrump.com, is the following plan: “Remove barriers to entry into free markets for drug providers that offer safe, reliable and cheaper products. Congress will need the courage to step away from the special interests and do what is right for America. Though the pharmaceutical industry is in the private sector, drug companies provide a public service. Allowing consumers access to imported, safe and dependable drugs from overseas will bring more options to consumers.”

The indicated desire to remove barriers could signal a reduction in government regulations like LaGrelius is advocating for – a more traditionally Republican approach. On the other hand, Democrats like Cummings and Chiu show no signs of ceasing their efforts to create government oversight to get a handle on drug costs.

“At some point, I think the American public will get fed up with the sticker shock and the fact that citizens, small businesses, the largest companies and everyone in between are struggling to pay for health care and we need solutions,” Chiu said. “And I don’t think this issue will die off until we have some relief from skyrocketing drug prices.”

Which way will the pendulum swing? As both Chiu and LaGrelius said: we will see.