Coyotes have become an increasingly noticeable fixture in Southern California since the 1970s, when the animals began moving into neighborhoods, running through streets and backyards gobbling up trash, pet food and pets themselves. Since a coyote attack resulted in the death of a young child, Kelly Keen, in Glendale in 1981, wildlife researchers and government agencies have struggled to identify urban coyotes’ behavioral patterns and a plan to manage them. In doing so, these entities have had to toe an emotionally charged line between upset residents concerned with public safety and equally concerned animal rights activists who believe coyotes deserve protection, too.

That’s the urban coyote narrative as related by Robert Timm, Ph.D., the retired director of the University of California (UC) Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources’ Hopland Research & Extension Center, who has spent his entire career studying and teaching about wildlife. He has often lent his expertise to agencies when wildlife and human interactions become problematic, as has been the case with urban coyotes for the better part of the past four decades.

The City of Long Beach recently released a new Coyote Management Plan at the direction of its city council following a string of recent sightings and pet deaths. (Image by Christopher Bruno)

Recently, Timm provided formal input to the City of Long Beach’s Animal Care Services Bureau, an arm of the Long Beach Department of Parks, Recreation & Marine, when it was developing a new Coyote Management Plan. The Long Beach City Council directed animal care services to come up with a new plan this August after a rash of reported sightings in the Lakewood Village neighborhood in the northeastern part of the city, as well as other areas.

Coyotes may have originated in the Great Plains or Southwestern United States, and are now found in the 48 mainland states of the U.S., and throughout Canada and Mexico, Timm said in an interview at the Business Journal offices. Some argue that coyotes are moving into urban areas because humans have taken over their habitats, which may be true in some cases, he explained. Still, they are much more abundant now than they have ever been.

“The difficulty is there is so little research on coyotes in suburban and urban areas because it is so hard to do,” Timm said, explaining that there are too many variables at play, such as how coyotes tend to traverse private property lines and have even been known to use sewer systems like highways.

Robert Timm, Ph.D., is the retired director of the University of California’s Hopland Research & Extension Center. He has authored reports and organized symposiums about urban coyotes, which have become a fixture throughout Southern California and the United States. (Photograph by the Business Journal’s Larry Duncan)

“The problem is that coyotes, when they live in suburban [and] urban areas, typically find ample food resources and sometimes are intentionally fed by people,” Timm said. “Sometimes it’s unintentional – people just don’t realize that wildlife are making use of the groceries, pet foods, pets, and the garbage and the compost piles, while everybody else is asleep.” These are all attractants for coyotes, as are bodies of water such as ponds, birdbaths or pools.

“What happens is there is this habituation process that is pretty predictable,” Timm said, referring to a process by which coyotes become used to urban environments and the people and their pets that occupy them. “It’s a series of about seven steps where they get increasingly bold.”

These steps of behavioral escalation were first published in 1998 by Timm’s colleague, Rex Baker, a now-retired professor from California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, who recently collaborated with him to provide input to the City of Long Beach on its Coyote Management Plan. In 2007, Timm and Baker co-authored a report entitled “A History of Urban Coyote Problems” through the University of Nebraska. Baker’s steps include:

1. Increased coyote presence on streets and in yards at night;

2. An increase in coyotes non-aggressively approaching adults and/or taking pets at night;

3. Coyotes present on streets or in parks and yards during morning or afternoon hours;

4. Coyotes chasing or taking pets in the daytime;

5. Coyotes attacking or taking pets while they are on a leash or near their owners, and coyotes chasing joggers, bicyclists, and other adults;

6. Coyotes present around children’s play areas, schools or parks in the midday hours;

7. Coyotes acting aggressively toward adults in midday hours.

“One of those steps is they start attacking and killing pets,” Timm said. “When they start doing that in the daytime, then it becomes very problematic and some of those coyotes are eventually going to become aggressive toward people.”

Ted Stevens, manager of Long Beach Animal Care Services, told the Business Journal that of the 96 pet attacks associated with coyotes so far this year, 47 were confirmed to be attacks by a coyote. In some instances, Stevens’ staffers may have been called to pick up a deceased animal that was apparently mauled or eaten. In these instances, the city considers the pet death to be linked to coyotes.

The majority of these incidents involved cats, although some involved dogs. Cats make easy prey for coyotes, which Timm said eat just about anything from rats to fruit to snails. “They actually will kill dogs, and they will kill dogs larger than they are,” he said. “They will sometimes gang up on dogs. I have seen pictures people have shared with me from Orange County of German shepherds that were badly mauled, and even pit bulls, sometimes. Little dogs and middle-sized dogs are no match for them at all.”

The city has seen an increase in coyote sightings and pet-related incidents during the past two years, Stevens said. He noted that, since assuming his position four years ago, coyotes have consistently had a presence throughout the city. “It kind of moves around the city to different areas,” he said of coyote activity. “Last year was the Belmont Shore area and Seal Beach, which is [also] our jurisdiction. This year it was Lakewood Village, the 5th District by the airport. And a couple months ago, Naples.”

Ted Stevens is the manager of Long Beach’s Animal Care Services Bureau. He oversaw the development of the city’s Coyote Management Plan, and has discretion to authorize the lethal removal of coyotes from neighborhoods in certain situations. (Photograph by the Business Journal’s Larry Duncan)

There have been no recorded coyote bites or attacks on people in Long Beach this year, or in any city records for previous years, Stevens said. But, in addition to pet attacks, news of bites and attacks in other cities may be putting residents on edge, he speculated. “Obviously we had our issues here, but because of what happened in Irvine this summer, everyone is kind of feeling like we’re next.”

According to Niamh Quinn, Ph.D., the area vertebrate pest advisor for the University of California South Coast Research and Extension Center, there were six recorded coyote bites on humans in Irvine this year.

In Los Angeles County, there have been 14 coyote bites on humans reported thus far this year, a public information officer for the L.A. County Department of Public Health told the Business Journal via e-mail. The representative noted that the county records bites only in cases where skin is broken, and does not keep data on non-bite attacks for any animal species.

Coyote attacks on children are not uncommon, according to Timm. “There have been lots of attacks on small children, many of which have been interrupted by an adult who happened to be present and prevented the child from having serious injury or maybe even being killed,” he said. “There is pretty strong evidence, and I think it probably is true in the Kelly Keen case, that coyotes regard small children as prey items. They are small enough.” Keen is the only known human fatality associated with a coyote attack.

In order to prevent coyote behavior from escalating to such an aggressive degree, Timm and Stevens both emphasized that it is necessary to educate the public about coyote attractants and to implement hazing measures. The City of Long Beach Coyote Management Plan, released in October, places heavy emphasis on these components.

The plan contains three main pieces, including public education about how to coexist with coyotes, enforcing regulations that prohibit feeding wildlife, and “ensuring public safety by implementing tiered responses to coyote behavior.”

The city’s plan places strong emphasis on hazing coyotes in order to deter them from habituating or developing aggressive behavior. Hazing is meant to instill weariness or fear of humans in coyotes via such methods as yelling, using noisemakers, throwing projectiles like cans or sticks, or even spraying them with hoses.

“If the coyotes are not terribly habituated around people, hazing may in fact delay further habituation, or it may cause them to be somewhat more weary of people,” Timm said. The longer coyotes remain in urban areas, which are quite noisy, the more difficult it is to get them to respond to hazing techniques, he noted.

“Rex’s [Baker] own experience in the neighborhood he lives in out in Corona was some of the coyotes that were out there early on could be shooed away fairly easily by noises,” Timm said. “Then, as the coyotes habituated further to the environment and got used to the fact that being in suburbia is kind of noisy at times, it was less and less easy to get a reaction out of them. Even when shooting .22 [rifle] blanks at them, it at some point didn’t faze them any more,” he recounted. “They gradually learned that they owned the neighborhood and were quite comfortable.”

In a recent experiment in Colorado, teams of volunteers regularly went out to local greenbelts and parks where coyotes had been spotted to haze them, and initially had good results, Timm said. “They said the coyote sightings became fewer and fewer, so they thought it was pretty successful,” he explained. “After about four or six weeks, they stopped the hazing, and two weeks later a father with two small children was attacked by coyotes.” He concluded, “Those animals were already bold enough that the hazing didn’t make an impact on them, other than they knew how to avoid the people who were doing the hazing.”

A previous city coyote management plan rolled out in Long Beach in 2014, Stevens said, and the tiered response system has since been updated to allow coyote removal – trapping and euthanizing a coyote – at a lower behavioral threshold. “We lowered what constitutes a higher aggressive coyote and lowered the threshold for trapping,” he said.

Now, if there are three confirmed incidents of pet deaths or aggression towards people within two weeks, “targeted lethal removal may be implemented,” according to the plan. If a particularly severe single incident occurs, Stevens may elect to execute lethal removal without more documented incidents, he said.

Under the city’s plan, any documented attack on a human would result in lethal removal of a coyote.

The city has yet to trap and kill a coyote due to aggression, Stevens said. But animal care services does occasionally have to pick up deceased coyotes that have died of natural causes or from being hit by vehicles, and it sometimes has to euthanize sick or injured coyotes. “We have picked up somewhere around maybe four to five in the past few months that have either been dead or we have had to euthanize because they were injured,” he said. Annually, his department picks up anywhere between one to two dozen coyotes in Long Beach and Seal Beach.

Previous attempts to manage coyote populations in some areas in L.A. County, including Griffith Park, have shown that removing and killing a few coyotes from an impacted area can deter the animals from coming into contact with humans and pets for months, or sometimes years, according to Timm.

“When they start to become pretty bold around humans . . . if you don’t start thinking about removing a few animals selectively, I am not sure what else reverses the behavior at that time,” Timm said.

Stevens would advocate for removing a coyote only if its behavioral threshold met those identified as level “orange” or “red” in the city’s plan, which are defined by multiple pet attacks in a certain time span or an attack on a person. “If we see one start reaching this aggression level, we will remove a handful of them and try to target the ones that are causing the problems,” he said.

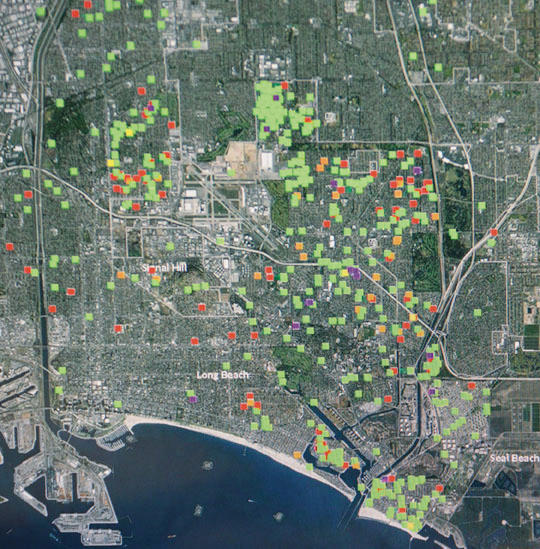

This map of Long Beach and adjacent cities shows recorded coyote sightings and related incidents as of October 27. This year, many sightings were clustered in the Lakewood Village neighborhood, shown at upper center, which is bordered to the north by Del Amo Boulevard, south by Carson Street, west by Lakewood Boulevard and east by Bellflower Boulevard. Green boxes indicate coyote sightings, red indicate a suspected coyote attack, orange represent pet attacks, purple denote a coyote “threat,” and yellow represent stalking incidents. The map is available at tsdgis.longbeach.gov/ACSActivity/coyote.html. (Map from Long Beach Animal Care Services)

Some animal rights advocates argue that coyotes should never be killed. Others argue that when coyote attacks have occurred, only the offending coyote should be killed. But that’s incredibly difficult to execute, Timm said. “It’s hard to determine who the bad actors are, because they all look alike to the average person,” he explained. DNA may be removed from deceased pets and compared to a coyote to determine if the right one has been caught, but “that’s very hard to do,” he said.

“Quite frankly, it becomes political so fast,” Timm reflected. “Most biologists have biological answers, but we don’t have enough training in politics or sociology to be able to manage it.”

On the one hand, there are owners of pets who have been attacked or killed, and concerned residents who are emotionally distraught at the prospect of living with coyotes in their neighborhoods. “I think the driving force is the people who are having pet loss, because that is the large number of people who are seriously impacted as families and as individuals psychologically,” Timm said.

On the other hand, “You always have some groups of folks who have plenty of money and lawyers who say, ‘We don’t want any coyotes killed for any reason at all. This is inhumane,’” Timm pointed out.

The Long Beach City Council, mayor and city staff members who were present at the August 11 city council meeting know these viewpoints are in no short supply in their city, as representatives from each side spent hours debating at a meeting that lasted until around midnight.

The result of that meeting was directing Stevens and his staff to come up with the Coyote Management Plan, which Stevens said took a “a balanced, fair approach.”

Timm, who still lectures and does some consulting work, said that, even after 27 years working in the UC system, there’s only one thing he knows for certain about the behavior of coyotes. “I have started telling students, there is only one rule about coyotes: there are no rules about coyotes.”