When Daniel Tapia, owner of Long Beach’s 4th and Olive Bistro and Wine Bar, worked as a sommelier and beverage manager at a Beverly Hills restaurant, he says he was pushed out due to his disability. The retired Navy submariner uses a cane to walk.

Instead of filing a lawsuit against his former employer, Tapia said he decided to channel his frustration into making a positive impact: starting a restaurant that focuses on hiring disabled employees, particularly veterans.

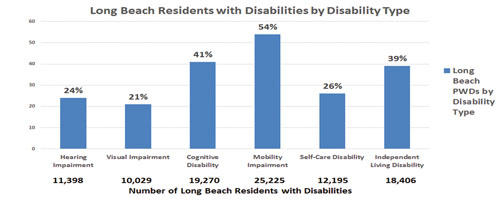

About 46,000 Long Beach residents have one or more disabilities. Source: Chart provided by RespectAbility.

Now, after its first year of business, 4th and Olive has approximately 15 employees; five of whom are disabled and eight of whom are veterans. According to RespectAbility, a national nonprofit organization dedicated to the empowerment and advancement of people with disabilities, Tapia is providing much-needed opportunity. Jennifer Laszlo Mizrahi, RespectAbility’s president, said that 34% of individuals with disabilities in the U.S. are employed. The number is even lower in Long Beach. According to a RespectAbility study, which draws on data from the U.S. Census, only 21% of residents with disabilities are employed.

“Business owners are reluctant to hire people with disabilities because they think it’ll be costly or time-consuming or distracting,” Philip Kahn-Pauli, RespectAbility’s policy and practices director, said. “But the process of integrating a person with a disability into your workforce can be straightforward and cost very little money.”

The disproportionate number of unemployed individuals with a disability relative to the total disabled population in Long Beach spurred the RespectAbility team to implement a project in the city, according to Kahn-Pauli. The organization found that 46,000, or roughly 10%, of the population in Long Beach is impaired. This falls below the national average of approximately 20%, according to statistics from the U.S. Census. But, despite their lower representation, more people with disabilities in Long Beach are unemployed compared to the national average.

The organization obtained its data through the American Community Survey, a yearly analysis conducted under the U.S. Census Bureau. It measures demographic information from the same areas evaluated by the census every 10 years. The Long Beach Health Department does not keep its own record of individuals with disabilities but references figures from the census.

Daniel Tapia, owner, 4th & Olive Bistro and Wine Bar. (Business Journal photograph)

Through a $25,000 grant from the Knight Foundation, which supports the city’s efforts to increase economic growth, RespectAbility is taking steps to ensure the workforce in Long Beach is more accessible to individuals with disabilities. According to Kahn-Pauli, the organization defines a disability as any impairment that impacts someone from entering the workforce and living independently.

“We look at physical and mental disabilities,” Kahn-Pauli explained. “A disability can include mobility impairment and limb loss, but we also look at mental health. About half of the population with a disability has a non-visible one. This covers autism, as well as intellectual and learning disabilities.”

RespectAbility broke down disabilities in Long Beach into categories: 24% of residents are affected by a hearing impairment, 21% by a visual impairment, 41% by a cognitive disability and 54% by a mobility impairment. In addition, 26% of the local population has a condition that makes it difficult to perform self-care tasks, such as bathing, dressing and eating, and 39% are impacted by a disability that prevents them from living independently. This includes the capacity to perform tasks such as preparing meals, using the phone and conducting housework, according to the U.S. Census definition. Many people have more than one disability, which places them in multiple categories, Kahn-Pauli said. This is why the percentages add up to more than 100%.

The RespectAbility team is taking a systematic approach to provide support for disabilities. After the organization received the grant in May, staff began the process of conducting research and forming local partnerships to improve early intervention and diagnosis. Some of the partner organizations include Long Beach Unified School District, Long Beach City College, AbilityFirst – Long Beach Center, Pacific Gateway Workforce Investment Network, as well as the mayor’s office. AbilityFirst is a California-based nonprofit that manages programs promoting progress in the disabled community. Pacific Gateway is a public agency serving Long Beach, Signal Hill and the area surrounding Los Angeles Harbor. It connects adults and youth to job opportunities, and employers to skilled workers.

“Our effort has been to work with local partners to identify key barriers and try to develop new strategies to overcome them,” Kahn-Pauli said. “Some of them match up with national barriers in terms of stigma and lack of understanding of disabilities. Some are physical like public transit access and getting in and out of buildings. Wheelchair users need other mobility aids to enter the workforce.”

Tapia said he has found that people with a disability are stereotyped as “unhip” and “uncool.” Or that sometimes, able-bodied people with helpful intentions take those intentions too far, which in Tapia’s perspective is almost as damaging.

“Some people think we need anyone’s help to do anything,” he said. “My body is already limiting my choices, I don’t need anyone else adding to that. I push my employees as hard as I would somebody with an able body. My job is not to baby them, my job is to open doors for them and let them do with [an opportunity] what they can.”

RespectAbility featured Tapia’s restaurant in its #RespectTheAbility campaign, which highlights companies that employ or are run by people with disabilities. When conducting interviews with Long Beach community members about desired resources, Kahn-Pauli found that many expressed a need for more role models in the disabled community.

“Something we heard from both the provider side and from self-advocates is that there’s a great need for mentorship opportunities,” he said. “The experience of having a disability can be very isolating. You might not have many role models to look up to.”

To address the “hunger” Kahn-Pauli found among parents of disabled children for more information, RespectAbility released a comprehensive catalogue of resources. These include family support organizations, employment services for adults, and college support organizations. The guide is also available in Spanish, which addresses a necessity unique to Long Beach, according to Kahn-Pauli.

“The majority of students with disabilities in Long Beach Unified [School District] are Latino,” he said. “This brings up issues like the need for early diagnosis and intervention as well as cultural conceptions of disabilities.” Kahn-Pauli clarified that RespectAbility does not identify someone speaking English as a second language as disabled. But, he said, a language barrier can pose a significant challenge for a parent in determining whether or not a child has a disability.

According to Kahn-Pauli, the organization’s key focus areas for improvement in Long Beach are employer engagement, the transition from school to work, and increasing early intervention and diagnosis from kindergarten through 12th grade. He noted that many students who drop out of school do so because they have an undiagnosed disability.

“This is the first segment of what we’d like to be a long-term project,” he said. “We want to see disabled students at Cal State Long Beach and Long Beach City College find pathways to internships and we want to develop a yearly parent resource fair. We’d also like to identify local partners who will take over the reins for us.”