The 220-acre Douglas Park, an office, industrial and retail business park adjacent to the Long Beach Airport, is a bustling center of commerce for the City of Long Beach. Companies representing a diverse array of industries call the campus home, from automotive parts suppliers to health care providers, engineering firms and more. But one of the sectors with the largest presence in the park has deep roots in the history of the land itself: the aerospace and aviation industry.

A C-47 crosses Lakewood Boulevard as it prepares to land on Runway 25R at the Long Beach Airport. In October 1962, Douglas Aircraft completed its $7 million, nine-story, 83,000-square-foot administrative building and an adjacent (pictured at left) three-story, 304,000-square-foot engineering and product development building. They stood for about 45 years until they were razed to make way for the development of Douglas Park. (Boeing photograph)

In the summer of 1940, Donald Douglas, president of the fast-growing Douglas Aircraft Company, and his vice president, Carl Cover, flew to Daugherty Field (now the Long Beach Airport) to inspect a potential site for an aircraft manufacturing facility. After a quick visit with city officials, Douglas and Cover agreed to purchase the 200-acre site at a cost of $1,000 per acre. Construction on the plant, Douglas’s third in Southern California, began in November of that year.

At the groundbreaking, Douglas made a statement that he couldn’t have known would not only describe his endeavor, but that of the future development of Douglas Park in the following century: “To do this important job we’ll need many new buildings, much new machinery and a lot of new men. All three are necessary, but the most important single factor is manpower, for without men and ideas, buildings and machinery are just steel and concrete.”

Douglas Aircraft constructed an 11-building facility encompassing about 1.42 million square feet of windowless covered work space for the wartime production of military aircraft, from bombers to cargo planes. Many of the employees at the finished plant were women, giving rise to the popular imagery of “Rosie The Riveter.” Peak wartime employment was 160,000 workers.

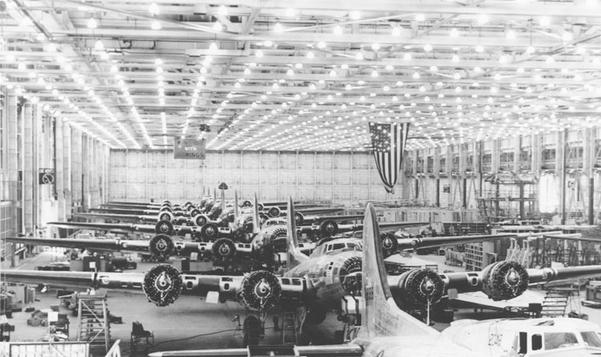

The C-47 “Skytrain,” a military transport craft, was the most well-known of the planes built at the Long Beach plant during World War II. The planes were used long afterward, seeing action in the Korean War and the Vietnam War as well. The second-most produced aircraft at the plant during the war was the B-17, a bomber with four engines. At the height of the production effort at Douglas’s Long Beach plant, the facility was turning out one plane per hour.

Following World War II, thousands of Douglas Aircraft company employees were laid off as government contracts were slashed. Women employees were encouraged to quit in order to give remaining jobs to veterans returning home. But the factory continued to turn out planes for the military, including the B-66 bomber and the C-124 Globemaster II (a predecessor to the C-17 Globemaster III, which Boeing ceased production of a few years ago).

This 1987 photograph shows the expansive production facilities of McDonnell Douglas that are now Douglas Park. (Boeing photograph)

In 1957, Donald Douglas Jr. took over Douglas Aircraft Company from his father. Under his leadership, production at the Long Beach plant shifted to commercial airplanes, beginning with the DC-8. The firm invested $20 million in a plant for the aircraft on the east side of Lakewood Boulevard, which opened in 1957. The 176-passenger plane made its maiden flight from the Long Beach Airport on May 30, 1958. The DC-8 and its subsequent versions held a 14-year production run in Long Beach.

In 1961, Douglas Aircraft split into two divisions, with the Aircraft Division based in Long Beach. The company built a new $7 million facility consisting of a nine-story administrative building and a three-story building for engineering and product development off of Lakewood Boulevard. The firm had developed a veritable corporate campus, and production of another commercial liner, the DC-9, soon commenced. The aircraft had a 17-year production run.

Production of commercial aircraft coupled with the development of new facilities resulted in growing expenses for Douglas Aircraft Company, which ultimately resulted in the company’s merger with McDonnell Aircraft Company, leading to the creation of the McDonnell Douglas Corporation in 1967.

The merger allowed the development of new aircraft in Long Beach to gear up at an energized pace. The plant began manufacturing the DC-10, a commercial aircraft capable of carrying 380 passengers. The first took off from Long Beach in 1970.

The economy took a hit in 1975, leading to companywide staff cuts and the transfer of employees from other Southern California plants to Long Beach and Huntington Beach. McDonnell Douglas continued to manufacture commercial airplanes. It also entered into a contract with the U.S. Air Force in 1977 to produce aerial refueling tankers and military transports, the latter of which ultimately were scrapped by the Carter administration.

The late 1980s were a time of prosperity for McDonnell Douglas, and brought about the C-17 Globemaster III, a massive cargo plane that was manufactured in Long Beach until just a few years ago. In the 1980s, the company also began producing the MD-80, a more fuel-efficient commercial liner that turned out to be an entry point into the market of the People’s Republic of China. Subsequent models of the plane were built through the 1980s and ’90s.

In 1985, McDonnell Douglas expanded in Long Beach yet again by increasing the size of its facility by two million square feet to accommodate production of the C-17, DC-10, MD-80 series and MD-11. Another $45 million building was constructed at the southwest corner of Lakewood Boulevard and Carson Street, as well as an office facility built directly across the street, opening in 1989. The latter still stands today.

The 1990s proved to be more challenging for McDonnell Douglas, as the company contended with a worldwide recession, rising fuel prices and reduced passenger loads on commercial flights. In 1990, the New York Times pointed out that the end of the Cold War meant the erosion of military contracts for the company, which the newspaper reported was steadily losing money. In Long Beach, 8,000 workers of the site’s 49,000-person workforce were laid off.

In 1996, Boeing bought McDonnell Douglas for $13.3 billion in stock, the New York Times reported, and the Long Beach Division of Boeing Commercial Airplanes was born. Boeing quickly assessed production lines in Long Beach and decided to rebrand the MD-95 jetliner as the Boeing 717-200. Contracts for the 100-passenger short-range twin jet were made with AirTran Airways of Florida, Hawaiian Airlines and others. The Long Beach facilities also became the site of commercial services support for Boeing customers and owners of McDonnell Douglas heritage aircraft.

During a three-year production run, Douglas Aircraft’s Long Beach plant produced 3,000 B-17s under license from Boeing Aircraft to support the WWII effort. The plane’s sturdy, four-engine design gave it superior range, speed and reliability. (Boeing photograph)

In May 2001, according to a 2006 article by the Orange County Register, Boeing cut 2,100 people from the workforce of 3,500 who were working on the Boeing 717-200. The company ceased production of the aircraft in 2006, by which time the number of workers in the program had already dwindled to 800. Two hundred of those were given the opportunity to transfer to the C-17 production line, which ultimately shuttered in 2015.

During the 65-year aircraft production history of the sprawling campus, more than 15,000 aircraft were built on the site, according to Boeing. By 2006, this chapter had been all but closed. Shortly thereafter, Boeing put the majority of its property surrounding Lakewood Boulevard up for sale. In 2008, a company called Long Beach Studios announced it would purchase the former 717-200 manufacturing plant to build a massive movie studio, but the deal fell through when the recession hit.

Following this loss to the city, then-Mayor Bob Foster, the city council and city staff partnered with Boeing to create a plan for the site, which went through multiple iterations until it was ultimately decided that it would be zoned and billed as an opportunity for a business park. The majority of the property was ultimately purchased and developed by Irvine-based Sares-Regis Group.

Although the site cannot claim to boast the same kind of employment numbers as it had at its peak in World War II, Douglas Park has risen from the dust of aviation history to become a new vision for Long Beach commerce – one with a varied workforce, community amenities, and international brands innovating for the future of several industries, including, yes, aviation and aerospace.

Editor’s note: The historical information in this article was sourced from the following publications produced by the Long Beach Business Journal: McDonnell Douglas 50th Anniversary in Long Beach, December 1990; McDonnell Douglas/Douglas Aircraft Company 1st 75 Years, 1995; and Salute to Boeing Southern California, November 2003.