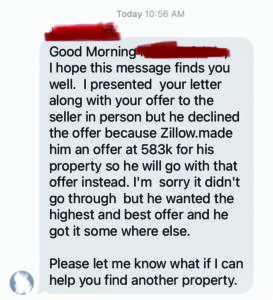

In early October, Natalie Hernandez got a text message from her real estate agent with disappointing news: The prospective first-time homebuyer had, once again, been outbid.

But this time, there was a twist. The seller of the North Long Beach house hadn’t gone with another young couple or a typical investor. Instead, Hernandez had been beat out by Zillow.

“It was devastating,” Hernandez said in a phone interview.

She had been in the market for more than a year and made about eight offers. The rejections didn’t get easier with time.

“It was really hard to get to the point where I even wanted to put an offer on a house,” she said. “I wasn’t just going to eight houses and bidding on all of them.”

Since then, Hernandez has successfully purchased another North Long Beach home. She and her partner received the keys earlier this month.

Zillow, as those who closely follow real estate news are already aware, has not fared as well. The company announced early last month that it would close Zillow Offers, the arm of its business that buys and resells houses like the one Hernandez sought.

“We’ve determined the unpredictability in forecasting home prices far exceeds what we anticipated,” Zillow Group co-founder and CEO Rich Barton said in a Nov. 2 statement, “and continuing to scale Zillow Offers would result in too much earnings and balance-sheet volatility.”

The news highlighted a small sector of the residential real estate industry that gained more attention during the COVID-19 pandemic: iBuying. Over the past decade, companies have sprang up whose sole business is buying homes online, sight unseen, and reselling them for a profit. Meanwhile, more established companies in the real estate sector, like Zillow and Redfin, have expanded their businesses to include iBuying as one of a number of other services.

The appeal for people looking to sell a home is obvious. iBuying services offer a quote—often priced to be competitive with what a house could fetch on the open market—and allow the seller to dictate closing and move-out dates. For many sellers who have used iBuyers, a major appeal is also the fact that it can all be done without anyone ever stepping foot inside the home—an aspect that became especially important during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Eva Mannoia, for example, sold her five-bedroom, two-and-a-half bathroom Laguna Hills home to the iBuying company Opendoor earlier this year.

Like many other families, Mannoia and her husband found themselves looking for more space during the public health crisis. But she was wary of the idea of people touring her house.

“I have a child with special medical needs,” Mannoia said, “so I didn’t really want to have people in my house, looking around, during a pandemic.”

A friend told her about iBuying, and she got quotes from Zillow and Opendoor.

“Opendoor’s [price] was vastly higher” than Zillow’s, she said, “and the process was almost uncannily easy. We could time it perfectly, and not a soul stepped foot inside.”

When asked if Mannoia was concerned about getting a higher price, she said Opendoor’s offer—$1.06 million—was higher, by roughly six figures, than three different agents estimated they could sell the house for on the traditional market.

“It worked very effectively for us. We happened to be in an excellent market where—they wanted to have inventory, there were very few houses available, the size of our house was exactly right, kind of thing,” she said. “So they were able to give us a very, very good offer on it, and in fact, when they sold it, they held it on the market for 45, maybe 60 days, and they sold it for less than they paid us for it.”

By going with Opendoor, Mannoia’s family didn’t have to spend all that time waiting for their house to sell. They were able to move into their new 4,100-square-foot house in Mission Viejo with minimal overlap in ownership.

Still, Mannoia said she recognizes the process may not work out as well for everyone. It’s always possible that sellers who go with iBuyers and don’t list their properties publicly are leaving money on the table—which could be a concern for people who want to get the highest possible price.

iBuying companies, for their part, see the routine hassles that people face in selling a house—cleaning, staging and coordinating open houses, which all comes before an escrow process that could include significant repairs and concessions to a buyer—as part of an antiquated system.

“We think consumers, regardless of their circumstances, want a more certain, hassle-free way to buy, sell and move,” said Andy Swanton, West General Manager for Opendoor. “Opendoor takes the complex traditional home transaction—a complicated and broken process—and makes it a simple and convenient way for homeowners to sell their house.”

“In our view, the end state for the real estate market will be a simple, certain and fast transaction,” Swanton added, “powered by technology.”

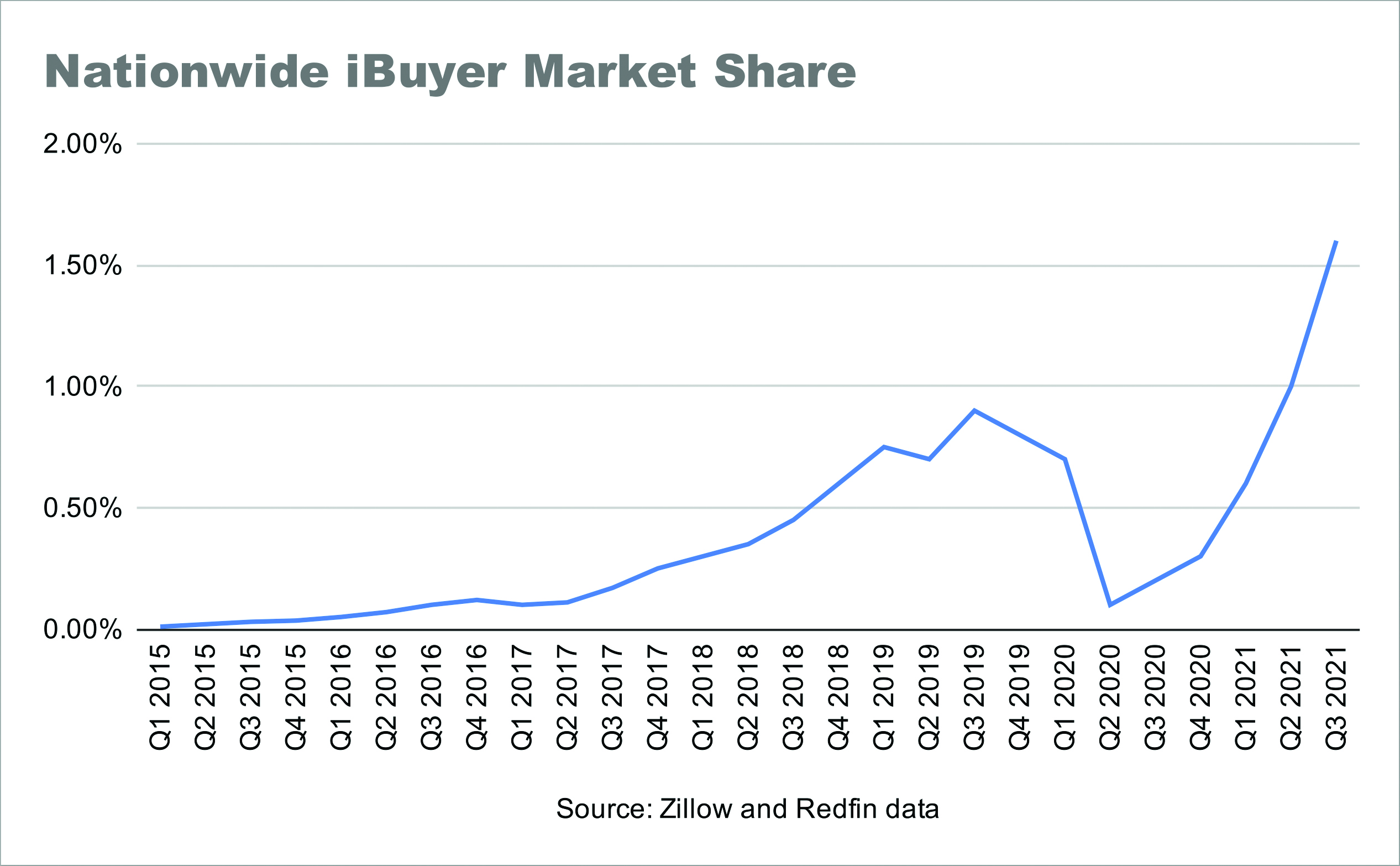

But iBuying still has a long way to go before it represents a significant share of home sales.

An analysis that Zillow published in September, which looked at iBuying purchases from the four largest companies, found that those transactions represented 1% of the overall U.S. market in the second quarter of this year. The Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim market was in line with that number, at 1.2%.

An analysis that Zillow published in September, which looked at iBuying purchases from the four largest companies, found that those transactions represented 1% of the overall U.S. market in the second quarter of this year. The Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim market was in line with that number, at 1.2%.

While those shares are small, they still represented a significant rise from the prior quarter, when 0.6% of home purchases nationwide and 0.8% in the LA area were by iBuyers.

Zillow, at the time, used the analysis as evidence that iBuying had a strong future ahead.

But two months later, the company announced a net loss of $328 million in its third quarter, leading to the decision to wind down Zillow Offers and cut 25% of its workforce. Some of the financial challenges outlined in the company’s third quarter report included having purchased homes at higher prices than they’re likely to sell for and capacity constraints that pushed sales of already purchased homes further into the future.

“We have offered sellers a fair market price from the start, but have also been clear that the business only becomes consistently profitable at scale,” Barton, Zillow’s co-founder and CEO, said in a statement. “With the price forecasting volatility we’ve observed and now must expect in the future, we have determined that this scale would require too much equity capital, create too much volatility in our earnings and balance sheet, and ultimately result in a far lower return on equity than we imagined.”

So where does this all leave the future of iBuying?

Representatives of other iBuying firms were quick to point out how their business models differ from Zillow’s.

Chris Edwards, for example, is the Southern California portfolio manager for Redfin’s iBuying arm, called RedfinNow. Edwards acknowledged that determining fair market value is far more difficult in some areas than others—and RedfinNow accounts for that.

He said Phoenix, where homes are relatively homogenous, is one of the easier markets to price.

“In other markets, like Southern California and San Francisco, it’s more difficult to value homes,” Edwards said. “There’s so many different factors—view and neighborhood and floor plan and schools. Properties are really different around here, and there are a lot of older homes, so it is a challenge.”

“But I think the strength of Redfin is that we have real estate experts,” he added. “This whole RedfinNow product—it’s not an automated offer. We have the Redfin Estimate, but we don’t use an algorithm to come up with an offer price. We have investment specialists who look at every offer that comes in and do a valuation and come up with a fair market value. By putting experts at the front of the process, we feel like we have good control of the offers that go out the door.”

Edwards, along with folks at Opendoor and Offerpad, said they believe their companies are poised for success with iBuying.

But Richard K. Green, director of the USC Lusk Center for Real Estate, isn’t so sure.

Green said that while the premise of iBuying is a solid win for sellers, it’s unclear how anyone makes a sustainable business out of it. Title insurance, property taxes and transfer taxes are all extra costs involved in a sale that may cut into a potential profit margin—and that’s assuming a house goes up in value.

“But that doesn’t always happen,” Green said. “If you’re caught at the wrong time, it can really bite you, and we saw that with Zillow.”

Zillow’s “algorithm is better than others—they have a lot of information,” Green added. “They’re sort of like—they and Redfin are both very good, like Google, constantly making their algorithm better, constantly upgrading it. If they can’t figure it out, I don’t know how other people can figure it out.”

Still, he said, “to some extent, I’m rooting for these guys to do well because the cost of buying and selling a house with all these commissions involved is absurdly high.”

Not everyone, though, is rooting for them.

Hernandez, in North Long Beach, said her experience shows how iBuyers can make an already tough market even more difficult for first-time buyers. Zillow outbid her and her partner by $43,000—a significant sum given the couple’s $560,000 maximum budget.

Records show the house sold Nov. 12 for $585,400, with a Zestimate—Zillow’s home value algorithm—of $552,900.

“I think Zillow and Redfin—iBuyers—shouldn’t be in the market, because they are an unnecessary player,” Hernandez said. “It’s a very competitive housing market. I’ve already been beat out by regular investors, out-of-town kind of buyers, and so Zillow—even if they don’t control, what do they say, more than like 2% of sales—they still cause housing prices, I think, to unnecessarily rise.”

But Green, at USC, said he’s heard that argument, and the data doesn’t support it.

“That is using anecdote to draw conclusions, which is what people do all the time,” he said. “It’s like saying, ‘I have cancer, and there’s a transmission box next to me, so maybe the transmission box caused my cancer.’ But when, in fact, systematic studies are done: No, they don’t cause cancer.”

Still, Green said, he understands the impulse.

“It’s hard for buyers to get in the market right now, so they’re looking for a villain,” he said. “If they want a villain—not that I would call it a villain, but 2.5% mortgage rates explain a lot about why the market looks the way it does.”

“Mortgage money is free right now because the expected inflation rate and mortgage rates are about the same,” Green continued. “Money is free, so it’s not a great surprise that there are a ton of people out there wanting to buy.”

While iBuyers may make a difference at the anecdotal level—one-off sales like the house Hernandez tried to buy—Green said their overall market share is so small, and the business model so tenuous, that “I just don’t think it matters very much” in the bigger picture of real estate.

For Hernandez, though, those anecdotal, one-off sales are still worthy of concern.

“It’s important to acknowledge, because there is a very local effect,” she said. “Folks see it on the news, and they’re like, ‘Oh, well who is really affected by that?’”

“It’s really happening in North Long Beach,” Hernandez said. “When it’s in our neighborhoods, it’s important.”