According to fire professionals locally and across the country, every minute that passes, a fire doubles in size. Response time is therefore crucial to saving lives and property.

In Long Beach, the fire department’s response time increased significantly over a 10-year period and, according to the department’s “2015 Year-End Statistics” report, was meeting national standards on less than half of its calls for service. For example, in 2005, 72.8 percent of emergency calls were within the standards set by the National Fire Protection Association. In 2015, that percentage dropped to 46.1 percent.

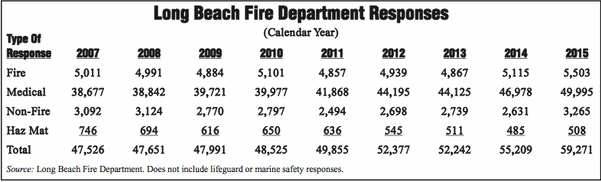

Fire Chief Mike DuRee says that as resources have been reduced due to budget cuts, calls for service have increased, straining the system and increasing response times. See top of next page for a nine-year comparison of calls for service. (Photograph by the Business Journal’s Larry Duncan)

Much of the reason for the slower response time is due to the reduction in equipment and personnel. Since 2007, as a result of the downturn in the economy, the department, according to Fire Chief Mike DuRee, has taken five engine companies, one fire truck company and one paramedic rescue ambulance out of service. There are also 84 fewer sworn firefighter positions and 15 fewer civilian positions.

Asked about the current situation, DuRee said, “It’s important to put it in perspective. Year after year, in a 20-year historical cycle, we see about a 2 to 5 percent call volume increase per year. At the same time, year after year, we take units out of service. In 2007, we took Engine 18 out of service on the east side. Our [citywide] system is dependent on all the parts. Just because you’re stationed in a specific geographic location, doesn’t mean you only run calls for service in that geographic location. Engine 18 at any given time could run a call to North Long Beach or downtown or wherever we need it. So when you take Engine 18 out of service, it requires the surrounding companies to fill the hole.

“I use this analogy: It’s like a baseball field. You put nine players on the field and, because of the salary cap, or whatever, you have to pull the shortstop off the field. Now you’re playing with eight players on the field. Can you do it? Yeah, you can do it. Based on your data, analytics and what your expectations are, you shift the players around a little and cover the hole. Then you take the first baseman out. So you can imagine you get to a place where . . . there’s a big hole to cover. Meanwhile call volumes continue to go up. That’s the situation we’re in today.”

The department responded to about 5,500 fires last year, ranging from trashcan fires to the recent full-blown fire at the Royal Buffet restaurant in Bixby Knolls.

“Royal Buffet is a great example,” DuRee said. “It becomes a third alarm assignment and I’ve got 15 fire engines over there, three trucks, all the battalion chiefs, and meanwhile all I have are three fire engines citywide to run [other] calls. I have no forced multiplication capability. So now we have rely on L.A. County, Orange County, L.A. City, and that’s a big issue.

“I’m a big believer that the fire service is here to preserve the economic continuity of the city and of the business community. I use the example of Lucille’s all the time. We had a small fire in the hood system at Lucille’s in Towne Center. The team got there fast, in four minutes, off the rig and, because we were staffed adequately, they go inside to put the fire out. It was up in the hood system that goes through the attic. There was extensive damage, but they put the fire out quickly.

“The fire was small in the grand scheme of things, but it was significant because it shut down the restaurant. The insurance company came in that night, they got a contractor and spent all night working on it. The next day they are open for lunch. If we showed up minutes later, the economic impact would have been devastating.

DuRee said if the tax measure passes, he would hope to restore the budget he once had, stressing that he still has the equipment that was taken out of service, but he needs the bodies to operate the equipment.

“The important thing is this,” he said, “it would be irresponsible for me to say, ‘I want to flip the switch, put five engines, a truck and a rescue in service.’ Would I like to do that? You bet. But whatever we do this point going forward, if new revenue comes in to the city, I have to be responsible with that so that five years down the road we don’t run the risk of having to take it out again. We want to be responsible and sustainable. We have to do it one at a time and see what’s happening with our system, and then go from there.”

At the time of the interview, DuRee did not know what his department’s share of the tax money would be, but he did indicate what his priorities are.

“Engine 8 would be the first thing I would put back in service,” DuRee said. “It was the last thing we took out, so it’ll be the first thing we put back. Second, I would restore Rescue 12, in North Long Beach. Third would be Engine 17 over in Stearns Park. Then right on down the list. To be realistic, even if we got new revenue and I was able to restore one thing, to put Engine 8 back in service, it will have a positive impact citywide. These are all city council directions. If there was new revenue coming in, if this [measure] were to pass, council will determine how much gets allocated and for what purpose.”

DuRee said the cost to restore a fire engine is $2.2 million, which is for personnel costs since he already has the fire engine. “That includes four personnel per day, so twelve bodies.”

In years past, finding people to hire through an academy class was not a problem. The last class, for example, had more than 5,000 applicants taking the written exam to get on the list for a future academy. But DuRee cautioned there may be some recruiting challenges ahead. “With the economy starting to get better, Los Angeles County, Los Angeles City and all 31 departments in the L.A. County region are starting to hire again,” he said. “So, unless we get to that list quick and scoop the best of the best off of the top and get them in to our academy, we run the risk of losing them. That’s what happened with our second class. A lot of the people that we reached out to said, ‘thank you, but I’ve already been picked up by another department.’”

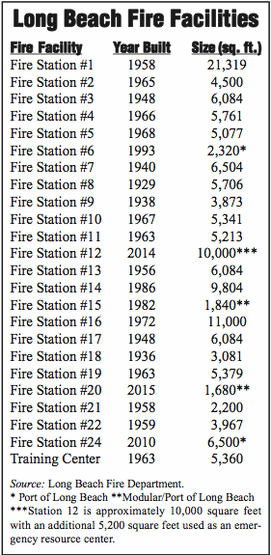

The top photograph is Fire Station 8 on 2nd Street in Belmont Shore, built in 1929, and above is Fire Station 9 on Long Beach Boulevard in Bixby Knolls, built in 1938. If voters pass the tax measure, Fire Chief Mike DuRee said the first priority is to return Engine 18 to the Belmont Shore station, eliminated several years ago due to budget reductions. The station also requires moderate upgrades totaling about $450,000, many mandated by the Americans with Disabilities Act. Station 9, which totals less than 4,000 square feet and is squeezed between commercial buildings, needs to be relocated and expanded at a cost in today’s dollars of about $10 million. (Photographs by the Business Journal’s Larry Duncan)

DuRee added that the current academy class, which is about halfway through its 16-week course, includes transfers from other departments, including two from Austin, Texas, two from Cal Fire [California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection] and three from San Diego. “We’re still attracting firefighters from other places,” DuRee said. “Long Beach is a destination city for the professional fire service. It’s a big department. There are a lot of opportunities for promotion, professional growth and development. It’s an aggressive fire department with a good reputation and it’s an appealing place for people.”

Once a class graduates, its members enter a one-year probationary period. “We start an academy with 24 people. Typical attrition in the academy itself? We’ll lose four to five people. They either opt out or drop out.” The annual attrition for the department is 12 to 15 people, DuRee said.

Currently, the department has about 460 sworn personnel. That includes firefighters, firefighter paramedics, captains, engineers, battalion chiefs, and seven managers, according to DuRee. There are another 40 people associated with the ambulance pool and about 50 civilians in the department. It does not include marine safety, which is paid from the Tidelands Fund.

The capital improvement project list prepared by the city’s public works department lists 33 items for the fire department, estimated to cost about $125 million. The list includes fire station upgrades – much of it related to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) – and station relocations. The fire chief was asked to explain the eight relocations listed, each with a price tag ranging from $8 million to $13 million.

“Let’s use Station 7 at 2395 Elm Ave., as an example,” DuRee said. “When it was built, there was nothing there except dairy farms to the north. Now it’s a residential community. So, is the station placed in the right place given the call volume and all the analytics we run now? No. It should be out on Long Beach Boulevard or it should be on Atlantic to give us a faster way to get us where we’re going. And it’s incredibly disruptive if you have a fire station plopped in the middle of your neighborhood. We would like to one day move that station to a place that will enhance our capability, but also get it out of that neighborhood so it’s not as disruptive.

“Station 12 is a great example, because that was at 65th and Gundry, right in the middle of a residential neighborhood. We relocated it out to Orange and Artesia. The response profile for the crew has gotten way better because they’re out on a busy thoroughfare. It’s become an anchor of the community now.”

He added that a lot of the renovations are “predicated on the need to update the stations to gender neutrality. We have a mixed-use workforce, and stations were not built for the people that we have today, nor the equipment that we have today, so we need to update.

“We’ve done the very best we can over the years with the dollars that we’ve received, which are really not much. Our number one priority is running calls for service, but these are things we need to address. These stations are starting to fall apart. Case in point: Station 4. We go in to make it gender neutral. We make new bedrooms and bathrooms, and while we’re there, we replaced the HVAC system. Go up on the roof, and it is completely rotted through on half of the roof over the apparatus floor. OK, well now we have to replace the roof. There’s another $100,000. This is what happens when you have buildings built back in the ’60s.”

According to DuRee, the list of infrastructure projects, and the complementary resources needed to properly serve the city, its residents and businesses are not a wish list. “These are items that must get done and will get done, it just depends on how long it’s going to take.”

DuRee stressed that every 911 call is an emergency situation for the person making the call. “When someone picks up the phone and calls 911,” he said, “at that moment, they’re having the worst moment of their life. We approach every one of the calls the same.”