In the early morning hours of Feb. 8, 1971, the earth below the San Fernando Valley began to rumble. The Van Norman Dam nearly collapsed, threatening to unleash the contents of the reservoir on the thousands of homes below.

But for those who still remember the Sylmar earthquake half a century later, the images that remain are those of two hospitals decimated by the 6.6 magnitude temblor. The destruction of the Veterans Administration and Olive View hospitals in Sylmar accounted for 49 of the quake’s 64 victims.

Twenty years later, another destructive earthquake hit Southern California. The Northridge quake with its 6.7 magnitude killed 72 people, caused over $20 billion worth of damage, and led to the evacuation of eight area hospitals after water pipes broke and the power went out.

The Sylmar earthquake led to the 1978 founding of the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, which regulates the seismic safety of hospitals. And later, after the Northridge quake, the California Legislature passed a number of new laws around building safety, including the Hospital Seismic Retrofit Program of 1994, which is still in effect, with its requirements becoming more stringent every few years.

Over the next 10 years, California hospitals, including all of the hospitals in Long Beach, will have to make changes to the structure of their buildings to conform to the standards set following the Northridge quake—costly changes.

Struggling to come up with the funds, hospitals are now asking the state to reconsider some of the requirements that were written into law over 20 years ago.

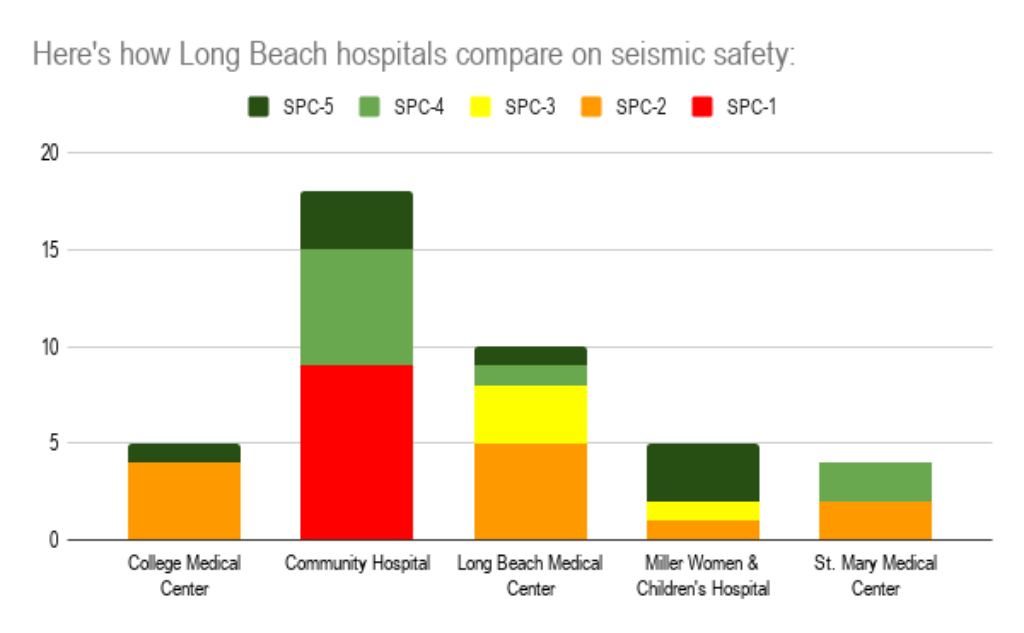

Since the passage of SB 1953 in the year of the Northridge quake, the state’s agency for health planning and development has rated individual buildings on hospital campuses based on their ability to withstand a major earthquake.

Buildings in the lowest structural performance category, SPC-1, had to be retrofitted or replaced by 2008, although hospitals could apply for exceptions to that deadline, in some cases extending it to 2025. To meet these requirements means that a building is no longer at a significant risk of collapse in the event of a major earthquake.

Except for Community Hospital, which is expected to complete retrofits by 2025 as required, all Long Beach hospitals currently meet this standard.

In 10 years, however, hospitals will come up on another deadline, requiring them to bring any building that houses inpatient services into compliance with an even higher standard.

This is where hospitals, represented by the California Hospital Association, are pleading with the state to reconsider its calculations.

According to the 2030 standard, hospitals have to be “reasonably capable” of providing inpatient services after a hypothetical—but, according to scientists, inevitable—major earthquake event.

The necessary retrofits and replacements come at a significant cost. A 2019 study conducted by the RAND Corporation and funded by the hospital association, estimated the total cost of statewide compliance to be between $25 billion and $105 billion, depending on how many hospitals choose retrofitting instead of replacement to meet the new standards.

These figures include the cost of updating “non-structural performance categories,” such as fire sprinkler systems, in addition to structural changes such as adding steel beams or wrapping concrete in carbon fiber to make buildings more earthquake-resistant.

Some operators have also pointed out that the fact that all hospitals in California must complete their construction work by the 2030 deadline, two years after Los Angeles is expected to host the Olympics, could create a surge in demand for construction services and supplies, further driving up the cost of compliance.

To bring down those costs, hospitals are asking state regulators to reconsider whether every hospital building that houses inpatient services needs to be capable of providing a full range of those services after a major earthquake.

Elective procedures—while an integral part of a hospital’s inpatient care services—likely wouldn’t have to be provided in a disaster zone, immediately after a major earthquake, said Jan Emerson-Shea, vice president of external affairs at the California Hospital Association.

“Does it really make sense to have every service that a hospital provides be able to operate?” she asked.

Which types of hospital care could be considered non-essential after an emergency and therefore be exempt from seismic requirements is still to be determined, said Emerson-Shea.

The hospitals’ plea has found the support of at least one California legislator, who has introduced a “spot bill” to address the issue in the current legislative session.

State Assemblyman Joaquin Arambula, D-Fresno, a former emergency room physician who represents Fresno and the northern part of the Central Valley, this year introduced a bill that would require hospitals to submit, by 2023, a list of each building, detailing the specific services provided.

While the bill is likely to change over the course of the legislative session, in its current form it would provide better understanding of the types of services each individual hospital provides and where they are housed, laying the groundwork for the potential exceptions sought by the hospital association.

“At minimum, we need an assessment,” Emerson-Shea said.

Last year, a bill that sought to establish a committee that would identify alternatives to hospital care in the event of a major disaster, authored by State Senator Anthony Portantino of La Canada Flintridge, was amended numerous times and eventually died in the assembly.

For now, local hospitals are drawing up plans to meet OSHPD’s requirements as they stand today.

Community Hospital, the only hospital in Long Beach whose campus still includes buildings that are considered at significant risk of collapse in a major earthquake, is in the process of retrofitting its facilities to meet the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development’s 2030 standards within the next five years.

An early estimate put the overall costs of retrofitting the hospital, which was built in 1924 and sustained only minimal damage as a result of the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, at $60 million, according to construction manager Ben Grubb.

While Grubb hopes a recent request for proposals will result in a lower overall project cost, the hospital’s age and location on a faultline have made meeting seismic compliance standards especially tricky. “We’ve got every curveball you could probably imagine [thrown at us],” Grubb said.

The hospital just recently reopened, offering only a portion of services for now, after being shut down for several years due to seismic safety concerns.

Dignity Health’s St. Mary Medical Center, the oldest acute care hospital in Long Beach still in operation today, counts two buildings that will need to be replaced or retrofitted by 2030, including the Bauer Tower, which houses the main hospital patient units.

The hospital’s original building, erected in 1923, was destroyed in the Long Beach earthquake of 1933, then rebuilt in following years by the founding nuns, the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word.

Dignity Health did not provide comment on the status of its compliance plans, nor did leadership at College Medical Center, which will need to bring four of its buildings into compliance by 2030.

Plans for a retrofit of MemorialCare Miller Children’s & Women’s Hospital Long Beach were approved by OSHPD last year and will cost the hospital approximately $20 million to perform, according to Chuck Coryell, executive director of plant operations.

Funding for retrofits at Miller Children’s & Women’s Hospital comes from a variety of sources, including state bonds that were approved by voters in 2018, but are exclusive to pediatric facilities.

When it comes to retrofitting or replacing the five Long Beach Medical Center buildings that would become incompliant in 2030, including the hospital’s main tower, there are currently no state funds available to support the project, according to Chief Operating Officer Ike Mmeje.

“It’s an unfunded request,” Mmeje said. It’s too early to say what the full scope of the project will be and how much it will cost, Mmeje said, but funding it will be a significant challenge the Long Beach Medical Center and its operator MemorialCare will have to grapple with.

“That’s us and every other hospital in California,” Mmeje said.