Increased demand has sent crude oil prices above $70 per barrel, well above budgeted projections for oil producers who were wary after a turbulent 2020. The strong and stable prices will allow producers such as the city of Long Beach and Signal Hill Petroleum to begin drilling new wells, according to local industry leaders.

For fiscal year 2020, Long Beach budgeted for an anticipated $21.4 million in oil revenue based on a per-barrel price of $55. However, demand plummeted early in the pandemic amid stay-at-home orders, which resulted in a $7.2 million shortfall, according to Bob Dowell, director of Long Beach Energy Resources.

The city, which partially owns nearly 2,400 active and inactive oil wells, budgeted for $35 per barrel for the 2021 fiscal year, which began Oct. 1. West Texas Intermediate and Brent crude oil, meanwhile, were selling for $73.74 and $74.88 per barrel, respectively, as of July 6, according to Bloomberg.

But higher prices do not always translate to more revenue, Dowell said.

“Many times, when you see increases in oil prices like we’re seeing now, expenditures go up,” Dowell said, noting how increased activity in well workovers and drilling usually follow increasing revenue.

California Resources Corporation, which operates most of the city’s wells, set a conservative investment strategy for 2021, Dowell said. The company halted drilling operations in April but will likely resume in September, he said.

Without new drilling, Long Beach oil production decreases 7-10% annually, Dowell said. In 2020, city wells produced 8.5 million barrels of oil. Since new drilling did not occur, the city expects to generate around 7.9 million barrels this year.

Most of Long Beach’s oil is produced at its THUMS Islands operations just off the coast, which pump from the Wilmington Oil Field. Even with new drilling activity, the oil field’s production decreases around 5% each year. Based on the rate of decrease compared to the cost of operations, Dowell said Wilmington will reach the end of its economic life in 2035—possibly sooner or later depending on prices in the coming years.

Once operations are no longer viable, the city is on the hook for more than $140 million for the proper abandonment of the wells. The state, meanwhile, will have to pay more than $900 million. The city’s unfunded liability for abandonment is more than $90 million but, despite the challenges of the past year, Dowell said he fully expected to be able to cover the full cost when the time comes.

The city also is responsible for mitigating former well subsidence—the gradual sinking of land area that occurs after oil has been extracted, which requires the injection of fluids—to the tune of $186 million. According to Dowell, the city already has set aside sufficient funds.

Despite not drilling since 2019, Signal Hill Petroleum, which operates hundreds of active and inactive wells in the small city, production has remained flat, according to Executive Vice President and COO David Slater. The company expects to produce around one million barrels this year and anticipates restarting new drilling in the fourth quarter, Slater said.

“From our perspective, looking at geopolitics, supply and demand, economies reopening, prices are more likely to go up than go down,” Slater said. “But we have no crystal ball.”

Global oil production has not kept up with demand, Daniel Yergin, vice chairman of IHS Markit, an information provider, recently told CNBC. The price of oil could very well break the $80 per barrel mark for the first time since October 2014, he added.

Rapidly increasing demand outpacing supply has caused gas prices to jump, particularly in Southern California, which often sees increases thanks to the required summer blends, Slater said. Demand is actually higher now than pre-pandemic, he added.

With most of its wells a stone’s throw from residential and commercial buildings, safety remains paramount to Signal Hill Petroleum, Slater said. Even while significantly reducing operational spending amid the pandemic, the company focused on maintaining its infrastructure. With more revenue coming in, the company is redoubling its infrastructure investment.

“We have several fairly significant infrastructure projects underway right now,” Slater said. “We do a high level of integrity testing of all our pipelines and facilities to ensure they are in good working order.”

Overall, Slater said the company is in great shape and is working on a number of deals to acquire smaller operators. For legal reasons, Slater did not provide details on the potential acquisitions.

While the industry appears to be thriving, oil producers—including Signal Hill Petroleum and the city—always have one eye on state and federal legislators. Slater said there are a number of active bills that would impact the industry. He declined to identify specific bills but said the company supports some and opposes others based on cost-benefit analysis.

“We are working hard to be a partner in achieving climate goals and support renewable energy in all forms,” Slater said. “But we also are very staunch advocates for having a diverse energy supply until the potential renewable energy replacements are robust and reliable.”

Some of the legislation is pushing toward renewable energy too quickly, while simultaneously pulling back on fossil fuels, Slater said. But renewable energy production has not scaled up to a level to replace traditional fossil fuels, he said, which creates concerns about blackouts due to energy shortages, especially during warmer summer months.

Californians already pay a premium for fuel and energy, according to a California Center for Jobs and the Economy report. Electricity prices in the state are 65.2% above the national average and remain the sixth highest in the nation.

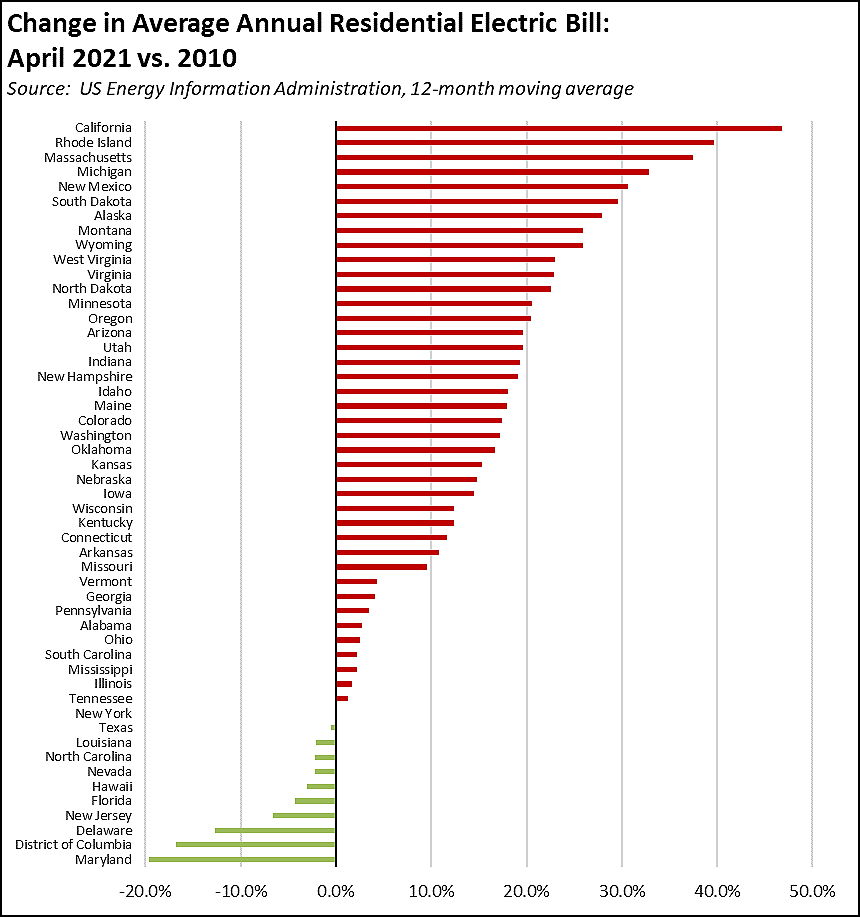

From 2010 to April 2021, the average annual residential electric bill in California increased $46.8%, compared to an average 5.9% increase in other states, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Since 2010, electricity cost increases in California have far outpaced other states, with costs actually dropping in 10 states and remaining unchanged in New York.

Commercial and industrial electricity prices are even worse, coming in at 79.6% and 128.4% over the national average, respectively.

As of July 1, California’s fuel tax increased $0.006 for a total of $0.511 per gallon, keeping the state’s fuel taxes the highest in the country. After a 10 cent increase from May, the state’s average gas price in June was $1.26 per gallon above the national average, the highest in the country. At $4.21 per gallon, the state had the second highest diesel price just behind Hawaii.

Even with strong prices and forthcoming drilling, Dowell could only describe the oil production industry in Long Beach as “surviving.” In the past, the city was supported by contracted service providers mostly based in the LA Basin. Today, after many businesses moved or shuttered, Dowell said a lot of services are provided by companies as far away as Bakersfield.

California Resources Corporation filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in August and has since restructured and downsized operations, Dowell said. Similar actions by other companies are inevitable as society moves closer to the end of extraction activities, he added.

“Stronger prices help, but overall we’re one of the more heavily regulated industries to start with,” Dowell said. “Between the legislative side and the business aspect, it’s becoming more and more challenging. But we’re hanging in there.”