This May, youth and young adults from throughout Long Beach will have the opportunity to participate in Long Beach’s first citywide participatory budget process.

Participatory budgeting, known as PB, is a democratic process that empowers residents to decide how to spend public dollars—in this case, $300,000 of funds from Measure US, which Long Beach voters approved in 2020. Measure US provides annual funding for public health, climate change efforts and children and youth services and programs across the city.

To kick off the process, a specific set of nonprofits—those that provide summer youth projects and programs in Long Beach for youth aged 8 to 24—were invited to submit ideas to support the city’s youth strategic plan. The deadline for those groups to submit ideas is today.

Potential ideas can range from summer camps to academic mentoring, financial literacy, housing support and beyond—as long as they aid the goals of the youth strategic plan, which include supporting health and wellness, planning for the future, and providing community care, housing and transportation. They must also fall in the range of $10,000 and $75,000.

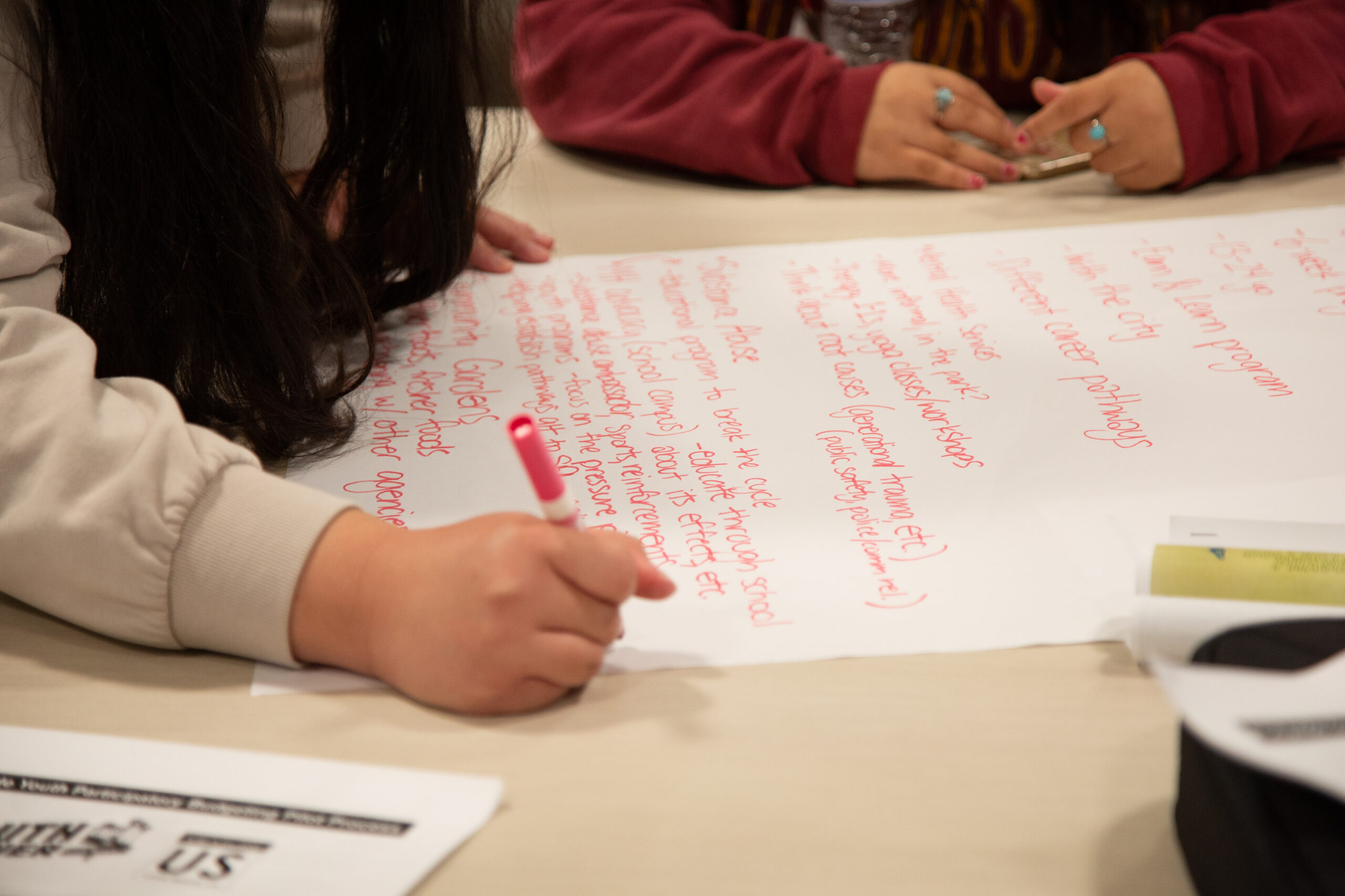

Throughout April, budget delegate teams will work to develop submitted ideas into proposals before a 10-day process in May in which youth ages 13 to 26 who live, learn, work or play in Long Beach will be eligible to vote for the summer programs.

Winning proposals will be determined based on the number of votes received. Funds will be disbursed to those with the most votes until the money runs out.

Information about each proposal will be available both online and through an in-person voter fair, and each person will have four votes and can submit one vote per project. Ballots will be offered in English, Spanish, Tagalog and Khmer.

While participatory budgets typically focus on infrastructure, the Youth Power PB Long Beach campaign focuses on programming, and it will be facilitated by the Invest in Youth Coalition in partnership with the city of Long Beach, the Long Beach Office of Youth Development and The Nonprofit Partnership.

Participatory budgets are designed to build capacity among organizations and individuals around political participation, but in this case, the youth piece is particularly important, explained Cal State Long Beach professor Gary Hytrek, who is serving as a consultant and evaluator.

“We know from research that youth who are engaged politically and socially are much more likely to be engaged as adults,” Hytrek said. “We know that our communities are more healthy. They’re safer. They’re better communities when residents are engaged in the public life.”

Initiated in Brazil in 1989, participatory budgets were first introduced to the United States in 2009, and are now practiced in over 7,000 sites around the world.

Work has been ongoing since 2013 to implement participatory budget processes in Long Beach, when the Long Beach Coalition for Good Jobs and a Healthy Community held a series of meetings for City Council members, their staff and community organizations to learn about the PB process.

In the spring of 2014, Councilmember James Johnson launched the first Long Beach PB pilot process, when residents of the 7th District voted on how to spend $200,000. By the summer of 2014, then-Councilmember Rex Richardson initiated a fully-developed PB process in the 9th District.

Two additional pilot PB processes were held from April through June 2015, in Council Districts 1 and 3—in District 3, Councilmember Suzie Price conducted a youth program, the second youth PB process in the U.S.

It’s clearly a process that works, said Christina Hall, a program manager for The Nonprofit Partnership.

“Why not take a play out of some of the cities that we see on the East Coast and other countries that have a chunk of the city budget for participatory budgeting, and that the whole city can vote on?” Hall said. “We’ve tried it in Long Beach and some of the districts, but what if we had a portion of the actual city budget that was a participatory budgeting process?”

Being part of a participatory budget process allows community members more insight into what certain processes can look like and what it takes to make a specific improvement, said Hall.

Through participating in this type of process, residents learn how difficult, costly and time-consuming it really can be to fill a pothole or develop an afterschool program, Hytrek said.

“You don’t read a manual and learn how to ride a bicycle. You ride a bicycle by riding a bicycle,” Hytrek said. “People learn how to become citizens, residents of communities, by doing the work, but often … there aren’t those opportunities, and PB creates those opportunities.”

As a new approach to budgeting, developing civic engagement and voting, there is typically a concern that people will vote for “really weird kinds of things,” however, residents tend to vote for traditional items such as filling potholes and improving local parks, Hytrek said.

“There’s that unknown element and the trusting of residents that has to happen that we’re not used to,” Hytrek said. “We really need to take small steps. … You’re seeing these processes work and work well, providing that basis upon which we can make the case for broader processes.”

According to Hytrek, a participatory budget process is one of the most effective ways to deepen and broaden democracy within communities.

“We’ve seen this over and over again, where residents, youth get to know each other, cross-racial, cross-class, cross-generational and also cross-political lines. … They may disagree on a lot of things, but what they agree on is their community needs certain things, and they can come together around those issues,” Hytrek said. “The partisan divide that we see kind of goes away, because they have a common purpose.”

In that way, a participatory budget can help to reverse low levels of trust, Hytrek said.

“It demonstrates to each other, to all of us, that we are responsible, that we can make the right decisions, if given the opportunity to do so,” he said.

A participatory budget is also a way for those with decision-making power, such as elected officials, to truly understand what the priorities are of residents—or in this case, youth—rather than just assuming what the needs are, Hytrek said.

“I think these organizations want to find more inroads into how they can do more of this bottom-up programming, and have youth involved in building out the programming versus what we think we’re hearing from our youth or what we think we’re seeing in the community,” Hall said.

Young people should be valued as decision-makers, even though structurally, that is not always possible, said Joy Yanga, communications director for Khmer Girls in Action, the nonprofit that anchors the Invest in Youth Coalition.

Public council meetings are typically not conducive for young people to attend due to late hours, and youth are not given a voice when it comes to electing school board members, who have a direct impact on the districts where they spend most of their time, said Yanga.

“This process expands decision-making for young people … especially for youth that come from under-resourced and structurally neglected districts,” said Yanga. “It’s really taking real money, like actual money, and saying, ‘Hey, what are some real solutions to the issues that you’re facing?’”

While it is still unclear what ideas or proposals could be voted upon, youth have indicated a need for mental health support, Yanga said.

“When we zoom out, and we take a look at what the pandemic had brought forth, it’s exposed a lot of structural barriers to help people access health and resources, but in addition to that, we also see an increase in homelessness and housing (instability),” Yanga said.

While this is just a pilot process for a citywide participatory budgeting process, Yanga hopes that there will be an opportunity to make it, or something like it, permanent. It’s a critical tool, she said, particularly for youth, who are typically excluded from voting.

In the future, being able to fund proposals that go beyond the current $75,o00 cap will also be key, she said.

“Some of the work that is very pivotal and critical for intervention and transformation for communities that need it most, do take either multi-year or even higher budgets, larger budgets to do so,” Yanga said. “This is a start.”

But overall, Yanga said, it’s good for youth to have an opportunity to shape institutions—at the city level, but also, she noted, in schools, where young people spend most of their waking hours—in a way that will prioritize their own health and wellness.

“You know that when youth are thriving, we all thrive too,” Yanga said. “It’s a good indicator that we’re doing well as a society when young people are doing well.”

More information is available here and on Instagram.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Gary Hytrek’s last name, the number of votes each participant will get and a quote from Joy Yanga.